“We all belong to the sea between us,” wrote the Cuban American poet Richard Blanco. Our global ocean, the least accessible yet most critical set of ecosystems on Earth, has seemingly always been a source of spiritual and creative inspiration. The sea is the setting of dreams, of trauma, peace, beauty, curiosity, cleansing, aspirations, new life, ancient life, and unknown life in the dark for leagues and leagues between (and beneath) us.

For more than thirty years now I’ve been lucky to read, teach, and write about the sea, often while aboard ships gazing with students and fellow authors upon a 360˚ saltwater horizon. The open ocean is a big place, of course, and our relationship with this most expansive and influential of Earth’s ecosystems is as varied, vast, and complex as human history and culture. Yet, perhaps needless to say, due to centuries of racism and misogyny, written works set at sea in English—fiction, nonfiction, and poetry—have been predominantly published by white authors, most of whom were men (myself included and likewise privileged). I adore and continue to be inspired by the sea stories crafted by such icons as Herman Melville, Joseph Conrad, and Rachel Carson, as well as those by the likes of Sarah Orne Jewett, Farley Mowat, and Mary Oliver. But dozens of extraordinary works by writers of more diverse identities somehow managed to emerge and publish classics of the genre, while more and more are being created and printed every year.

Below are just ten great works of sea literature in English by people of color.

The Deep by Rivers Solomon

“She couldn’t determine which was worse: the pain of the ancestors or the pain of the living. Both fed off her.” So thinks Yetu, the young protagonist of The Deep, who is charged with the weighty task of holding the horrific memories of her entire underwater society, to archive their history yet not burden all the other individuals with the daily sufferings of the remembrance. Author Rivers Solomon, in collaboration with hip-hop musicians Daveed Diggs, William Hutson, and Jonathan Snipes (who had composed music riffed off the work and mythologies of previous multi-media artists), crafted a novel of a submarine world after the Middle Passage. This world of wajinru beings with Yetu as historian is composed of descendants of the thousands of pregnant human women who died and were cast overboard, as well as those women who were forced or chose to jump into the waters instead of living and subjecting their children to the terrors and inhumanity of enslavement. The Deep has a fantasy façade, but like all profound science fiction, or any sea literature for that matter, its message and struggle are crucial for our navigation of today’s world on land.

Tentacle by Rita Indiana, translated by Achy Obejas

Set in the Dominican Republic, this work of cli-fi, speculative fiction, bends the rules of this list in that it was written first in Spanish as La mucama de Omicunlé (2015)—the English translation is by the Cuban writer Achy Obejas—but I can’t resist slipping Tentacle in here, because Rita Indiana spun such a fascinating story of a beach town ravaged by global warming, overfishing, drugs, and capitalism. Prisoners watch Blue Lagoon in a room that despite the fans and the shade bakes at 115˚ F: “Movies in which the sea is full of fish and humans run in bare skin under the sun are now part of the required programming during this season, just like movies about Christ during Holy Week.” Short, profane, and punchy, Tentacle explores the art world, Spanish colonialism, gender, sex work, coastal tourism, and marine conservation. This is truly a 21st-century work of sea literature.

The Cat’s Table by Michael Ondaatje

It’s difficult for most of us to understand how central were ships and the ocean to travel and emigration before the recent age of the affordable airplane. Michael Ondaatje’s novel The Cat’s Table takes us aboard a steamship on the most important voyage of a person’s life (before they can look back and realize this to be so). The Cat’s Table is a fictionalized memoir of a boy’s voyage by steamship across the Indian Ocean and north, from Sri Lanka to a new life in Britain. In the masterful hands of Ondaatje, this recollection of an ocean passage is told personally, seamlessly, and subtly while it explores memory, childhood, class, race, and sexual awareness. Deceptively languid and breezy, The Cat’s Table serves up a rite of passage, a slice of a life and a world that is both familiar and foreign.

An Aquarium: Poems by Jeffrey Yang

Yang is an editor, publisher, translator, and poet, yet some of his earliest training was as a marine biologist. In this A-Z verse bestiary of ocean animals, from “Abalone” to “Garibaldi” to “Nudibranch,” from “Parrotfish” to “White Whale” to “Zooxanthellae,” Yang wove philosophy and politics with careful, scientific observation, helping the reader envision these animals in beautiful and compelling new contexts. He often tucked in post-colonial commentary in deceptively simple ways, such as in “Jellyfish”:

“Occasionally a crab tires of its slant-

wise ways and stowaways

on the bell of a jellyfish…

Perhaps one day both wash ashore:

the jellyfish dies, and the crab

rediscovers a new world.”

The Ordinary Seaman by Francisco Goldman

Picking up a century after James H. Williams, Francisco Goldman wrote of the plight of merchant mariners. Instead of essays, however, he created a suspenseful novel about Central American immigrant men trapped on a derelict bulk carrier that is rusting in Brooklyn at the whims of distant owners. Docked within the barbed wire of the shipyard with little knowledge of English, they have no way to get help or justice. For centuries of sea literature, ships might as well be floating prisons, and in The Ordinary Seaman this plays out intensely, if ironically while tied at the wharf: “Nowadays life on the Urus almost feels like the middle of a long ocean crossing on a real ship—the lassitude, people keeping to themselves, bored with one another, not much to do but play dominoes and tinker around or endlessly chip or paint.” That is, until Esteban begins escaping each night and finds a sympathetic bilingual lawyer. Goldman is a master of characterization, which he achieves through flashbacks and daydreams. Before the story is over, he’ll teach you how our material goods get shipped across the oceans—and by whom.

Omeros by Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1992, published two years earlier his epic poem Omeros, which he spun from Homer’s Iliad. Omeros is mostly set in St Lucia among the turtle fishermen and islanders. Although it references classical Greek poetry, Walcott wrote with local dialects from multiple perspectives and brought the sounds, sights, and smells of the tropics. With his readable verse and shape-shifting, time-traveling narrators, Walcott gave dignity, texture, and gravitas to communities of everyday Caribbean people in the past and present. Omeros closes with a small gift of mahi-mahi that leads to a universal theme of sea literature: the smallness of human endeavor in comparison to the indifference and immortality of the ocean:

“Achille put the wedge of dolphin

that he’d saved for Helen in Hector’s rusty tin.

A full moon shone like a slice of raw onion.

When he left the beach the sea was still going on.”

The Whale Rider by Witi Ihimaera

“The muted thunder boomed under water like a great door opening far away,” says the narrator in The Whale Rider, a novel in which a female child is chosen to resume a centuries-old relationship where “the whale burst through the sea and astride the head was a man.” Witi Ihimaera was involved in the movie Whale Rider (2003), but the original work, the first Māori novel published in English, is quite different from the Hollywood version, including a more nuanced view of the colonial impact on indigenous New Zealanders. In the book the narrator travels to other parts of the Pacific and offers an illuminating perspective on the Polynesian Renaissance of the 1970s and ‘80s. Ihimaera based the story around a couple of actual events, including a mass stranding of sperm whales on a beach in Aotearoa New Zealand. In The Whale Rider he layered in spiritual retellings of Māori stories and even the perspective of the whale. If you can find one, I recommend reading an edition with Ihimaera’s “Author’s Notes” and the accompanying Māori glossary.

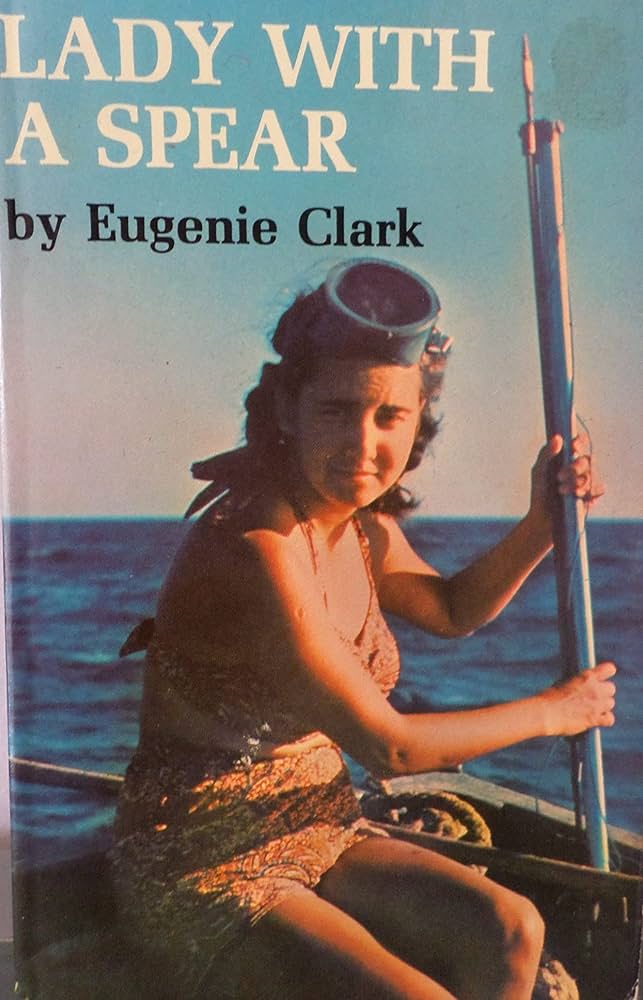

Lady with a Spear by Eugenie Clark

In the midst of the surge of ocean interest after World War II, Eugenie Clark published likely the first memoir by a female marine biologist. Her Japanese mother let young Eugenie explore the aquarium downtown on her own and took her swimming out on the beaches of Long Island. Beginning first with “underwater goggling,” diving with only a mask and fins before the availability of modern SCUBA gear, Clark earned her PhD and became a leading biologist of fish, sharks, and rays. She had a lengthy career as a professor and founding director of the Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida. Clark was a favorite of National Geographic and had a gift for what is now called science communication. Lady with a Spear, the first of her books (out of print, but easily found), recounts her early career spear-fishing and studying reef fish and sharks in the Middle East and the southeastern Pacific. She described adventures like this at a marine lab on the Red Sea: “We were munching on the last of the mermaid meat at lunch one day, when the old Rais, the ‘chief’ among the sailors, came rushing to tell us that a giant devilfish had been caught alive. We ran out to see it.”

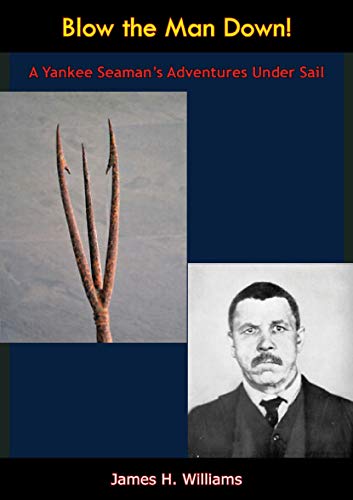

Blow the Man Down! (c. 1897-1922, anthologized 1959) by James H. Williams

Blow the Man Down is a collection of rare newspaper articles by James H. Williams, a sailor-author who grew up in Rhode Island the son of a white Irish mother and a Black father. His dad was a mariner and died young, so as an early teenager Williams began his life at sea alone. InBlow the Man Down, edited by Warren F. Kuehl, Williams recounts his decades around the world in the merchant marine and on whaleships with a level of detail that is invaluable to historians. Williams also knew how to spin a yarn, so, much like Dana and Melville before him, he entertained with tales of storms and shipwrecks as he revealed the injustices bore by sailors. Williams became a labor leader, organizer, and public advocate for sailors’ rights. “I was only a sailor and, like most others of my class, had a sublime and abiding reverence for law and order,” Williams wrote in The Independent in 1902, which is anthologized here. “But there is a point at which patience ceases to be a virtue, and where oppression becomes the parent of rebellion.” Many of his stories speak to this, and, while the Blow the Man Down collection can be hard to find, it’s worth the extra effort. If it’s not at the library, there’s a Kindle version for sale or it’s available for free on archive.org.

The Heroic Slave by Frederick Douglass

One of America’s most gifted and important orators, Frederick Douglass first learned to read as an enslaved boy working at a shipyard in Baltimore, then he later escaped to the north by dressing as a sailor. In his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), he described how for many enslaved people in the nineteenth century the vision of the sailing ship offered freedom, both literally and figuratively. Lesser known today is Douglass’s novella The Heroic Slave, which was likely the first work of fiction in English published by an African American person. Here Douglass used the tools of fiction, playing with point of view, allowing his readers to be inside the heads of both white and Black characters. His protagonist, Madison Washington, leads a rebellion to free smuggled Africans and sail them to British-held Bermuda and eventual freedom. In The Heroic Slave a white sailor relays later what Washington declared while steering the ship in a hurricane: “Mr. Mate, you cannot write the bloody laws of slavery on those restless billows. The ocean, if not the land, is free.”

Acknowledgments

Richard J. King thanks David Anderson and Alison Glassie for introducing him to some of these titles over the years.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.