Supporting writers and readers costs money—$500,000 a year, to be precise—and we need your financial help to sustain our work. Today, we’re asking you to give Electric Literature the gift of another year. We need to raise $35,000 to get us through 2025 and balance the budget for 2026. In these challenging times, we need our community to step up. The world is a better place with Electric Lit in it—let’s fight to keep it that way. DONATE NOW.

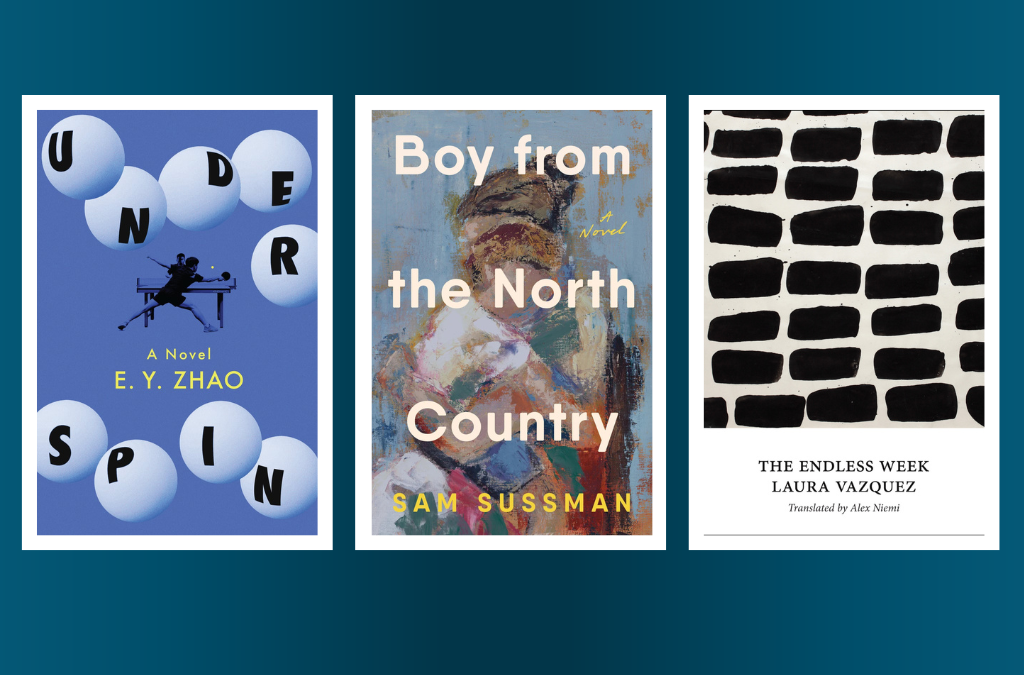

The debut novels we are featuring this fall are remarkably different in almost every possible aspect. One, Underspin, is a polyphonic novel that roves across perspectives surrounding a circuit of competitive table tennis players in the 2000s. Another, Boy from the North Country, moves between the present in a pastoral house in the Hudson Valley—where the narrator is raised by his mother—and the 1970s in a rent-stabilized Manhattan apartment frequented by Bob Dylan. The third, The Endless Week, is a novel immersed in the dialogue of thought that focuses on two siblings in search of their lost mother—while a slipstream of phrases, aphorisms, and proverbs left by their father follows them through an estranged language of ghosts and the internet.

Despite structural, tonal, thematic, and stylistic differences, these three authors share a great appreciation for harmonizing their characters’ voices and a fascination with the way the counter-experiences of play and grief can resonate and ricochet off of one another. From table tennis to painting to poetry, the characters in these novels demonstrate a deep need and desire to become almost child-like in their creative or competitive natures. By returning to a place of innocence and curiosity, they ask what it really means to win and whether there is an absolute purpose to art-making. In different ways, each author’s exploration becomes a source or path towards healing, remembering, and honoring a loved one. Ultimately, across their many divergences, these authors do seem to overlap in one instance. Through the interweaving of voices, ideas, egos, and personalities, they have each developed a plurality of narrators that come together to create a coherent and glistening web: the book.

This fall, E.Y. Zhao, author of Underspin; Sam Sussman, author of Boy from the North Country; and Laura Vazquez, author of The Endless Week are our craft interview debut novelists. In our discussions, we touched on the initial inspirations behind their projects, the many different consciousnesses a narrator embodies, and the idea of revision as a construction site.

Kyla D. Walker: What was the research process for the novel like and have you ever been involved in the competitive table tennis circuit?

E.Y. Zhao: I trained and played competitively in American tournaments from the ages of 9 to 15, then basically quit because school took up too much time and I’d burned out. I played freshman year of college and the second year of my MFA, competing in the National Collegiate Table Tennis Association with my club teams, but since then the most I’ve played is for book-related research and events.

At its most intense, my training looked like twelve combined weekly hours of group sessions, private sessions, and competition time at the St. Louis Table Tennis Club, and two months over the summer when I’d train six hours a day. My coach ran a practice out of her basement in Chesterfield, Missouri, and my parents would drive me an hour’s round-trip after dinner. I’d compete in tournaments once every third month, probably, a lot around the Midwest, and twice a year at the big national tournaments in Vegas and Baltimore. But compared to kids who were at the top, that’s nothing. So I brought all that lived experience and my general sense of inadequacy to the novel.

To write the book specifically, I traveled to Düsseldorf, one of the world’s table tennis capitals, and interviewed players and managers at the Bundesliga team Borussia Düsseldorf. I also played in the amateur clubs at Borussia Düsseldorf and TTC Champions Düsseldorf. I wanted to understand pros better, their psychologies and concerns; turns out they’re beyond my imagination. I asked Dang Qiu, who I remember being just outside the Top 10, what he needed to improve to break through, and he kind of gave me a blank stare. Because at that level there are still technical tweaks, sure—see Coco Gauff changing her serve, for example—but everyone is fast and consistent with sufficient technique; so much of it is psychological, tactical, philosophical.

Returning to table tennis ten years after I quit competing has been fascinating and emotionally charged, to an unexpected degree. I’m more mature, but the feelings of insufficiency welled up faster than I’d expected. It’s given me a chance to refine and reexamine those feelings on the page. On the other hand, the community aspect, which was always my favorite part and not fully in my control when I was a kid who couldn’t drive or dictate her time, has deepened in a poignant way. I’m writing to you from Paris, where I spontaneously met the founders of Ping Pang Paris, a ping-pong social space. They range in background from national team players to newbies, but—unlike when I was a kid—their place in and love for the sport is not contingent on skill level. There was so much pressure to perform when I was younger, and now I finally savor the enjoyment and freedom I observed in table tennis-playing adults around me. It’s really bittersweet.

KW: Admittedly, table tennis is a very different sport from tennis. However, there are similarities and overlapping philosophies, and recently it feels as though pop culture has been fixated on tennis as well as the personalities behind the players. How has this and previous art around tennis (such as Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers or David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest) affected or influenced the novel, if at all?

EZ: One of my early influences was tennis star Andre Agassi’s memoir, Open, which came out in 2012. What struck me about Open was Agassi’s doubt and abjection. I first read it when I was twelve and already behind where I felt I should be as a player. There were no table tennis novels or memoirs accessible to me (and very few in general), and it was comforting to recognize myself in Agassi’s depiction of himself as a scared, lonely, bullied pre-teen. Even when he wins majors, he kind of glosses it by; as he writes, losses are more memorable and striking.

Beyond Agassi, art about tennis didn’t influence Underspin all that much. Maybe because I haven’t read Infinite Jest, but also because tennis is the “more winning,” the more glamorous, and the ethos of American table tennis to me was its grunginess, scrappiness, and outsiderness. I know there’s plenty of that on the tennis challenger circuit, for example, and those aspects of Challengers the movie resonated, but part of my motivation to write Underspin was portraying this underdog atmosphere.

A bit more on David Foster Wallace: It’s not just that I haven’t read Infinite Jest, but his general orientation toward tennis (in his essays) feels different than mine toward table tennis. He’s writing with not just belief in genius and transcendence, but belief (or delusion?) that he can somehow describe or analyze his way into it. Underspin depends on a few postulates: 1) The spectators who narrate the book can’t understand their idol, Ryan Lo, 2) the idol is enthralling for being flawed, 3) table tennis is a bit abject. So the pure, deranged, worshipful excess of the Federer essay did not belong in my writing universe.

Even now that table tennis has gained some standing after the Paris Olympics, you can glean the vibe from the fact that current World No. 1, Wang Chuqin, is lovingly called “Big Head,” and the World No. 1 before him, Fan Zhendong, was known as “Little Fatty.” No god-like nomenclature here.

KW: What was your favorite part of the writing process for this project?

EZ: Underspin is a bit of a tribute album. Every chapter recognizably calls on at least one writer. Herr Doktor Eckert’s chapter is Ishiguro. Susanne and Kagin borrow from A Visit from the Goon Squad. Kevin and Co. are from Mariana Enríquez. Kristian emerges from Adam Johnson’s “Dark Meadow.” I won’t generate the whole list, I want people to identify their own beloved writers as well, but I loved paying homage to the geniuses who made me a reader and writer.

KW: In Underspin, each chapter shifts to a different character’s perspective—sometimes in 3rd person POV, sometimes in 1st, even once in collective 1st—what was the most difficult part about this? And how did you decide on the style of POV for each character/chapter?

EZ: Here’s my shorthand for POV:

Present tense: The consequences of the moment are not yet available within the story.

First person: The motor / heart of the story is dramatic irony, tension between what the reader can understand and what the narrator is willing to say.

I drafted POVs instinctively and my first choice was correct for everyone but Kristian, which could either mean I did all right or I’m too stubborn to revise POV and you shouldn’t listen to anything I say. For Kristian, I initially jammed him in a shifting third-person story because I was afraid of what I’d have to write if I got “into his head.” Interestingly, I learned through writing Underspin that first-person can be the more “distant” point of view because of what the narrator withholds. As the writer, you ostensibly understand on some level what they are withholding, but you also participate in their self-occlusion.

It wasn’t hard to “switch,” per se; the most difficult aspect was probably finding an agent and editor who’d take a book switching POVs every twenty pages. But I did have a writer who read the manuscript for a contest say I didn’t really know how to write close-third. That stung, but hopefully it’s gotten better since then…

KW: How has your writing process or relationship to your writing evolved over time and especially after finishing Underspin?

EZ: I wrote twice as much material as made the final cut, and as a stubborn person with a fragile ego, it’s made me so much more comfortable with revision. I go into a draft knowing I’ll rewrite it at least a couple of times and trying to cherish that first-draft encounter for itself. Every round of revision brings something different and to get through the querying, submission, and publication process, I had to learn to enjoy that.

Kyla D. Walker: When was the moment you felt ready to begin writing Boy from the North Country? And what was that initial spark—such as an opening sentence, scene, or possibly the end—that kicked off the novel?

Sam Sussman: Boy from the North Country is a tribute to my mother. After her death, I knew that I needed to write about her life. It took years for me to begin. Around the one year anniversary of her death, I decided to take seven days away from the world. I read, wrote, painted, meditated, reflected on her life and mine. This became an annual tradition for me. Every year, between September 9 to 16, I would take off from work, power down my computer and phone, and spend those uninterrupted days at home, in the house where I grew up, outside Goshen, in the Hudson Valley. I found this time restorative and healing. One afternoon in the third year of this ritual, in September 2020, I was painting outside. The easel was set on the hill, overlooking the valley. As I moved the paintbrush across the canvas, I thought of a story my mother once told me about something that happened to her in a painting class when she was a young woman. I set down the brush, walked inside, and began to write.

KW: How did the settings of upstate New York and Manhattan help sculpt the story or shift the prose?

SS: Places are archives of memories and meaning. I was lucky to write Boy from the North Country in the two places in which it is set, the house in the Hudson Valley where my mother raised me, and the rent-stabilized apartment in the Yorkville neighborhood of Manhattan that my mother lived in beginning in the 1970s, and in which I now live. Each of these places are part of me, and I knew that Boy from the North Country would be a more powerful novel if I could capture their magic. The swaying pine trees. The howl of the coyote. The echo of the freight train that runs along the tracks down the valley. This is the soundtrack of my life in this home. My memories of childhood, of my mother reading to me on warm summer afternoons, of the last weeks of her life, which we spent here; all this I wanted to raise out of the landscape, the hills, the floorboards, and set into the book.

The apartment in New York has its own majesty. My mother lived in that apartment when she was pursuing her own life as an artist, before she was my mother. I felt us living here together, our lives in parallel, decades apart. Writing about that period of her life made me feel closer to her. Then there’s the added detail that her romantic relationship with Dylan began when she lived here, and he wrote part of Blood on the Tracks in this apartment. So on those nights when I wrote the chapters centered on their relationship, here in the apartment, space, time, and memory all seemed to come together.

KW: Evan’s mother plays such a huge, poignant role in the novel. This goes even further in the mesmeric Chapter Eight, where the novel’s consciousness belongs to her. What were some of the things you did to capture her voice and perspective on the page?

SS: The concept of “autofiction” is often invoked to describe a writer transferring her life into literature. For me, the “auto” has to be larger than the self. We are all the people we have loved and who have loved us. For me, writing a novel about my life meant writing a novel that draws on my mother’s life and wisdom. After her death, I learned that loss brings us closer to people in unexpected ways. She wasn’t here to speak to me, so I had to think more deeply than ever before about her choices and values. I had to become a more careful student of her life. Writing a novel drawn from our lives was a way of spending more time with her. She was also a writer, and had spent the last decade of her life writing a column for the regional newspaper. I reread her essays, and in some cases even wove her written words directly into mine. You could say there are parts of Boy from the North Country that we wrote together.

KW: Through writing a novel that so deeply explores the ideas of memory’s reliability and the stories that get passed down to us about who we are, do you feel you learned more about truth, beauty, and/or your own self in a significant way?

SS: My mother used to say, “There are two stories to every life.” She meant that our lives become the story that we tell about ourselves. This isn’t about the facts of our lives, or the reliability of memory; it’s about how we relate to facts and memories. We can tell the story of our life with love or bitterness, resentment or redemption, anguish or faith. That choice becomes who we are. My mother suffered many difficulties in her life. She used to say, “We are here to take the pieces of the universe we have been given, burnish them with love, and return them in better condition than we received.” Her death was the most difficult piece of the universe that I have received. Writing this novel was my way of burnishing her death with love and returning this devastating experience to the universe in better condition than I received it, with the hope that it finds other people who have lived through their own grief and feel uplifted by a story in which love is greater than loss. Of all the stories we can tell of our lives, that is the one by which I choose to live.

Kyla D. Walker: What was the genesis of or inspiration for The Endless Week?

Laura Vazquez: La semaine perpétuelle is a book I began writing during a residency at the Fondation Jan Michalski in Switzerland. It originates from several distinct figures, a young boy in his bedroom watching internet videos, a very old woman, bedridden and obese, who can no longer speak, a man living alone, obsessed with cleanliness, a young girl who sings in online videos, and a young man living in a water-damaged shared apartment, using drugs. Each of these figures possesses a voice. I simply had to follow each of these voices—they intertwined and created the book.

KW: How did you decide on the structure for the novel?

LV: The structure was imposed by the text itself, by the interweaving of voices. It resembles the root system of trees, it unfolds in branches, these branches intersect, touch one another. As always in my books, the structure imposed itself naturally, through the text, through the voices in the text, through their particular rhythm, their musicality, their movement.

KW: What did revision look like for this project?

LV: An immense construction site. In reality, when I write a book, there’s a first draft that follows, that attempts to follow all the paths, all the writing directions. This first draft is about one and a half to two times longer than the final text, that’s what happened for this book. So I reread and corrected this text dozens of times until reaching the final form. I know the final form is there when my corrections risk damaging the text and when I myself decide the orientation of things, when it’s no longer the text that decides. It’s a subtle moment to pass through, very subtle, but ultimately you just have to listen to the text. It’s the text that knows.

KW: How has your previous background in poetry influenced your prose?

LV: I think poetry can do everything. It makes poetry, books of poetry, but it also makes novels, narrative texts, it also makes theater, it can make investigations, documentary texts. Poetry is capable of taking on all forms, and it’s only poetry that interests me. My first books were identified as pure poetry books. It was later that I began writing narrative texts. It’s always poetry I’m seeking in writing, it’s all that interests me in a text.

KW: What was your favorite part of the writing process for The Endless Week?

LV: I don’t really have a favorite, but there are some parts I felt more deeply than others. I believe there are two parts that had a concrete and powerful effect on me. First, the sorts of songs, prayers that Sara makes to the grandmother who is bedridden and cannot speak. These sorts of prayers, love songs to the grandmother, have at moments an almost carnal sensation. Then, the grandmother’s monologues—she’s in dialogue with the past and the future. She hears the past and the future in her body. And then there’s this moment where the grandmother sees pain and the pain leaves her body. And then she has pity for the pain. That was a very intense writing moment.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.