Obsession is the pulse and connective tissue that joins the three very different novels in this edition of our debut craft series. I interviewed the authors to discuss how each found their way into the nature of obsession—whether through an idea, a character, or a voice that haunted their writing—and went about circumnavigating and poking holes into the way we fixate and dwell, the way we obsess over things that are at times mundane and others, profound. One novel follows a pair of tumultuous lovers obsessing over rare songs on beloved records. In another, a culture critic obsesses over the truth behind a friend’s death and the absence of “genuine” friendship in the digital age. The third explores a Muslim adjunct professor’s obsessive urge to find love, or a substitute for it, in the messy modern dating scene of Los Angeles.

These three novels also share a tendency to move across cities and landscapes, chasing protagonists who are pursuing wild desires and, in the process, exploring the way people change—or don’t change— alongside their address. From Clinton Hill brownstones to Chicago karaoke bars, from Berkeley record stores and L.A. farm-to-table restaurants to a hospital in Tehran, the characters in these novels travel and relocate, all the while attempting to grasp their idée fixe. The cities they live in become stars in the uncertain constellations of their lives: each desperate to connect point A to point B. A few characters return home as adults, trying to rediscover who they were in order to find out who they will be. Others avoid home as much as possible and instead become hooked on searching for someone to sit beside them in the passenger seat. In the end, their questions revolve around the same central idea: Does someone’s newest obsession define them more than their past? And at what point, does an object of fixation bleed into identity?

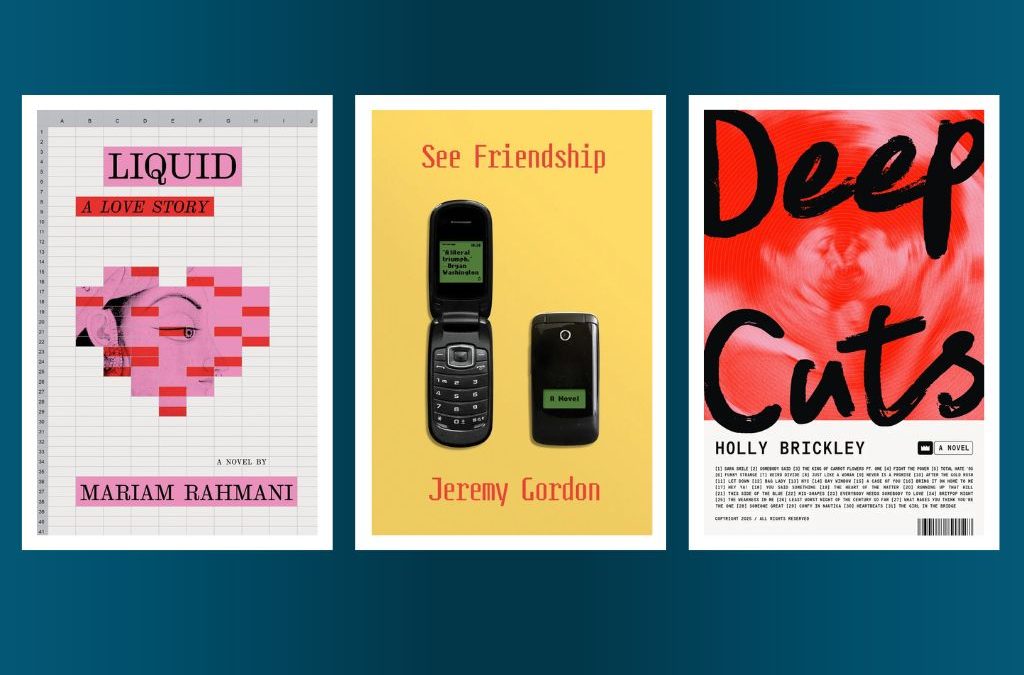

This spring, Mariam Rahmani, author of Liquid: A Love Story; Jeremy Gordon, author of See Friendship; and Holly Brickley, author of Deep Cuts are our craft interview debut novelists. They spoke with me about the initial inspirations behind their projects, the collapse of time, distance, and reality within a story, and how the voices of their protagonists came into being.

Kyla D. Walker: Did you write Liquid with an outline in mind? Or was the voice of the narrator the main guide?

Mariam Rahmani: Absolutely the former. For me, this book was a study in genre. I watch a lot of rom-coms and I’m always fascinated by how little surprise matters. You know the ending from minute zero—and often, frankly, can surmise the entire plot from minute ten. But it’s still so enjoyable, and even satisfying. I was really interested in staging that relationship between the text and the reader. I also had a few other questions for myself that operated as challenges. How smart can a rom-com get? Can a “serious” novel have a happy ending? Can an “ideas” novel be aggressively femme? The queer and racial politics in the book are also a little twisted, or at least not strictly celebratory—you don’t always know whom you’re rooting for—and confronting that discomfort was important to me. Can the politically sad choice merit celebration? I.e., can another brown woman ending up with a white guy (yes, that’s me, but also so many other women I respect from identities that, like the narrator, are not my own) still feel, in the heat of the text, like something to root for? What of the bi or queer woman who chooses heterosexual love? Is the personal always political? When it comes to biography, is everything always meaningful? Granted, I’d say that’s one big difference between life and fiction—in the latter, it is meaningful. Admitting that, I suppose I was asking about realism. How real can this shit get? Fiction, I mean.

KW: How did you nail the specifically witty, kinetic, and enthralling voice of this protagonist? Did it take a while to find and hone within the prose, or did it come naturally?

MR: I felt like a TV writer. I’d spend days “workshopping” a joke or line with the people around me, months thinking about it. There was also a draft where I ruthlessly cut out everything that fell flat.

KW: What was your thought process behind leaving the protagonist/narrator unnamed?

MR: I used to find unnamed narrators extremely annoying, a pointless kind of withholding. Then, years ago—I was reading a novel by a woman of color—I read the move as a political act. There can be a strength in that lack of access, a level of control that reminds the reader they only have access to what the narrator is willing to give. They only have access to those parts, or versions, of her body; those corners of her mind; those shades of her emotions.

So there was that. But really the decision wasn’t mine; it had been made for me by the history of the novel. My novel is a response—indeed, rejoinder—to the gendered and racialized violence that inaugurated Iranian fiction via Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl (1937), the first novel in Farsi. Hedayat’s unnamed male narrator has an Iranian father and Indian mother whom he exoticizes and fetishizes, the type of orientalization of India that has a long history in Iran. In order to enter that conversation, my protagonist had to have the same identity—but we get a woman’s perspective.

All that said, I liked how the lack of a name creates a sense of intimacy with the reader. It mimics love poetry—I’m thinking of a particular ghazal by Rumi, for example, where the refrain “me and you” chimes at the end of each couplet. Here the “I” of the speaker addresses the “you” of the reader. There’s even a moment or two in the book with “yous” that break the fourth wall, or act to generalize, rather than “one,” and pull the reader in. The reader becomes a kind of beloved.

KW: How did the cityscapes of Los Angeles and Tehran help sculpt the story? And why was it important to you to set the novel in both places?

MR: The book is a couplet: two halves that each make sense on their own but become altogether something else when paired together. It’s also a love letter to LA. That city was home to me for almost a decade, the longest I’ve lived somewhere on purpose (by which I mean, outside of the accident of where I grew up).

Tehran is similarly a city I formed a relationship with as an adult. My mother’s from there, and we started traveling back as a family when I was four, going not every summer but every two or three, whenever my academic parents could afford it. But when I was eighteen I chose to go alone for the first time, the summer before college. For years, I went once or twice a year, sometimes for work in a sense—I did my master’s research there for my degree in Islamic art and later, working in contemporary art in Dubai and New York, would go check out galleries, etc. Unfortunately, now I haven’t been since the pandemic. I wrote this book in 2022. Maybe I was homesick. (There is a part of me that will always feel that it’s home, as complicated as that is, and though I was born in the US. It’s a place that’s at once so far from me and so close.)

Politically, I’m interested in how similar the cities are. They’re almost at the same latitude, the climates are not so very different, they both have a lot of Iranians. But living in the US, existing in broader American culture, Iran feels very far away. Most Americans have no reason to think about it, and the ones who do often can’t access it given US-American relations since the Revolution. Liquid was a way to collapse that distance.

Kyla D. Walker: Did you write the novel with an outline or the ending in mind? Or was the voice of Jacob, the narrator, the main guide?

Jeremy Gordon: See Friendship initially began as a short story of about 9,000 words made up of essentially three scenes: a narrator reunites with a high school classmate at a bar in Los Angeles, where he discovers the true circumstances behind the death of a mutual friend; the narrator explains what he’s learned about these true circumstances, and the involvement of another former classmate, to his ex-girlfriend; the narrator comes face-to-face with the involved classmate in an interview for an untitled podcast project. Woven throughout these scenes were the narrator’s thoughts about his dead friend (their relationship, his death, and so forth), conveyed in a slightly world-weary, too-cool-for-school attitude about things that had taken place and could no longer be changed.

The project expanded and evolved in many ways: Jacob (my renamed narrator) became more fallible and less self-assured; the podcast went from being a tossed-in dynamic to a central pursuit; new characters were added that allowed me to sketch out different ideas and emotions. But I knew the novel’s instigating event was a revelation, and that the concluding event was a confrontation—and that, to take us from A to B, I wanted a charming, sincere, knowing, but not altogether correct voice. As I revisit the story today, it’s clear how I’d established the core structure of See Friendship—and, in fact, if I were to quickly summarize the book now, the elements of the initial short story would work in a pinch.

KW: See Friendship vibrates between light humor and stark tragedy remarkably well throughout each scene. How did you manage to sustain this emotional balance, and was it intentional to layer the prose with both of these elements?

JG: I do not always attempt to “write what I know,” but I always try to “write what I like”—and while I’d like to think I have a relatively diverse taste in literature, there is a certain sensibility that I always enjoy. It’s a tone that says “we’re dying, but let’s have fun”; it faces near-certain tragedy with the mirth required to not be overwhelmed by near-certain tragedy; it has the courage to tell a dark joke on what might be the worst day of someone’s life. A book that was on my mind during the revision process was Percival Everett’s Erasure, which pairs scenes of unbelievable sadness with some truly hysterical lines. This “laugh to keep from crying” approach has always resonated with me both personally and on the page, and it served as a helpful compass as I was revising and editing. When the book felt like it was getting a bit too self-serious, I tried to lighten it up; when I worried I was making a mockery of serious things, I remembered that Jacob is not meant to be a buffoon. A reader who finished the book told me: “My initial reaction was very sad, which is maybe not what I was expecting by the end because it was also very funny.” That twinned experience is, actually, what I was shooting for.

KW: What was your favorite part of the writing process for See Friendship? How long did it take from start to finish?

JG: I began writing the novel in the summer of 2019. I completed a first draft toward the end of 2020, then spent about a year-and-a-half revising it into the book that eventually went on submission. When all is said and done, nearly six years passed between breaking ground and publication, which seems sort of unbelievable even as I factor in the distorting effects of pandemic time. But, and I hope this doesn’t sound vague, this chunk of time did not seem so colossal because I continued to really enjoy the writing and revising process. There were a few points when I wondered how it was going, but never a moment when I doubted my commitment to seeing this specific project through to the end—and that self-knowledge, following some failed attempts at writing other novels, was invaluable. Sometimes, I’d look up after a long stretch of revising and rereading, and say out loud to my wife: “You know, I think this is still pretty good.” Or she’d ask me what I was laughing at, and the answer was: “My own joke.” To have that reaction several years into the process was really special, and informative—it confirmed to me that something in the writing was working, even when it felt like everything else was taking forever. That’s something for me to chase in the future.

KW: How has your background of being a culture critic affected your approach to writing fiction and this novel specifically? Did the transition to writing fiction feel natural?

JG: My earliest attempts at writing fiction, as an adult, seem ridiculous to me when I revisit them now: I was convinced that they had to “sound differently” than my regular writing as a culture critic, and so I labored to find a tone and voice that ended up being completely affected. It’s not that these passages didn’t sound like me, because I have no essential self that I need to sound like; it’s that they weren’t coming from a natural source. But when I started writing See Friendship, I realized that I had found a way to cut the shit. I was still laboring, but I wasn’t pretending to be another writer. And I think all the work I’d done as a culture critic had helped hone my sensitivity to what was and wasn’t working—because I knew what I liked, I could pursue that sensibility as my North Star in moments of doubt or crisis.

I’m working on a new novel that is, in many regards, very different from See Friendship; a couple of early readers have said as much. Yet it doesn’t feel like a “reinvention” or whatever; it’s coming from the same source of curiosity and inspiration that powered my first book. I think that hyper-awareness of what’s turning me on and what isn’t—for lack of a better phrase—is something that was shaped by my hours and hours of exposure to so many different types of media, whether in literature or music or movies or whatever else. Books are books, not movies or songs, but feelings and moods are cross-medium.

Kyla D. Walker: What was the genesis/inspiration for writing Deep Cuts?

Holly Brickley: The initial idea was to explore my lifelong envy of musicians in the context of a love story, where I thought it would make a good complicating factor. I knew I wanted to do it with a feminist lens, because that’s how I saw my envy, as a longing to be in the best of all the boys clubs; to have had, as a young girl, the carefree confidence that a young boy is so much more likely to have when he first picks up a guitar. Also, I’ve always wanted to write a rock novel, and I had this idea that by actually writing about songs—by weaving elements of music journalism into the fabric of a novel—I might have something new to offer the tradition.

KW: Did you write the novel with an outline or the ending in mind?

HB: No, I’m a pantser. Outlining never works for me because I get to know my characters as I write, and plot is driven by character. So I just felt my way forward, knowing the next one to two chapters and not much beyond that. I had a sense of where it would ultimately end up, but it was vague, and I had no idea how I would get there.

KW: How did you decide on the structure of a playlist for Deep Cuts? And did you decide on which songs you would use before writing the chapters?

HB: The idea to use songs as chapter titles came right at the beginning; that was part of my initial conception of a novel that actually analyzes songs. It was a little different at first, though. Some chapters read more like a traditional novel, while others were shorter impressionistic pieces focused solely on a song (no plot). Around the halfway mark, I jettisoned those shorter chapters, which I could see by then were unnecessary and probably pretentious.

As for whether I knew the songs before starting the chapter, that varied. Sometimes I knew with certainty from the beginning; sometimes I thought I knew, but changed my mind. And other times it took some effort to find a song capable of doing the emotional heavy lifting I needed. For example, there’s one chapter that was fully written, minus the song, for several days while I flipped through my records and yelled “Alexa, next! Alexa, next!” Finally, I found “The Weakness in Me” by Joan Armatrading, and not only did the song facilitate the emotional pivot I needed, but it took that pivot to a deeper place.

KW: What was your favorite part of the writing process for Deep Cuts? How long did it take from start to finish?

HB: I know this sounds crazy, but it was just a little over a year, from January 2022 to March 2023. I honestly loved every damn minute of writing this book, which is why I was able to write it so quickly—I was obsessed, writing every spare moment I could find, barely sleeping for nights on end.

If I had to pick a favorite moment, it was probably writing the penultimate chapter, “Heartbeats.” That was a fun scene for a lot of reasons, but part of it was that I could finally see how to land the plane I’d been flying, frankly, blind. That was an exhilarating moment.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.