Our fivesome of fantastic reviews this week includes Ron Charles on Gary Shteyngart’s Vera, or Faith, Anahid Nersessian on John Tottenham’s Service, Joyce Carol Oates on Caroline Fraser’s Murderland, John Ganz on Maurizio Serra’s Malaparte, and Lydia Millet on Will Potter’s Little Red Barns.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s home for book reviews.

*

“Few novelists risk jumping on the runaway horse of contemporary life as recklessly as Gary Shteyngart. For the fiction writer, stuck at the plodding speed of publishing, such a maneuver requires gauging both political velocity and cultural direction. And yet, book after book, Shteyngart arrives just where—and when—we need him to.

…

“The abiding miracle of Shteyngart’s work is that it seems just as timely as a Shouts & Murmurs gag in this week’s New Yorker while staying fixed to the timeless absurdity of human life. That dexterity speaks to the range of his sympathy and the depth of his attention. It may also stem from being born in the U.S.S.R.—little Igor Shteyngart emigrated to the United States in 1979; he knows in his kishkes how tightly the latest joke is braided through the oldest tragedy. Shteyngart’s new novel, Vera, or Faith, tastes at first like a cherry-flavored gumdrop, but it’ll burn a hole in your tongue.

…

“Lonely, precocious children in novels can be as appealing as a sticky handkerchief. But Vera is too self-possessed to be sentimental. Shteyngart, who captured his own awkward adolescence so brilliantly in his memoir, Little Failure (2014), lets us hear the melody of humor and the bass line of despair in Vera’s voice. Many of her concerns are minor, of course, but through her adolescent chatter, we can also make out the very real troubles corroding her world. Holden Caulfield responded to the ennui and existential despair of the Cold War by sinking into depression and glib cynicism; Vera reacts to our era’s deadly division with fits of perfectionism, striving to mend all conflicts everywhere. As ever, our political and social toxins collect in the brains of children like mercury.”

–Ron Charles on Gary Shteyngart’s Vera, or Faith (The Washington Post)

“For all its cheeky nods to actual celebrities both major and minor, Service is not an insider’s book, nor is it written for the cognoscenti. It is, rather, a book about the destruction of bohemia and the nightmare of trying to live—let alone make art—with very little money. Like Lynne Tillman’s great No Lease on Life (1998), which follows a young woman who works as a proofreader at a prestigious magazine and lives in the rundown East Village, Servicebelongs to a uniquely contemporary genre that might be called the novel of gentrification. It tells the story of what Richard Eder (reviewing No Lease on Life in the Los Angeles Times) described as ‘the new dispossessed: the low-income middle class whose only wisp of security is a toehold on a rent-stabilized apartment on a rotting block.’ In a country where tens of millions of people work service jobs and about one tenth of all jobs belong to the gig economy—jobs that are part-time, precarious, and often lacking health insurance—the newly dispossessed narrator may be the antihero we need.

…

“Unlike the relation between master and servant, the dynamic between customer and service worker cannot be openly acknowledged for what it is: the product of a social system in which one group of human beings is dominated and exploited for the benefit of another. The lie of the service economy is that we’re all friends here, and it is the job of people like Sean to maintain this lie, to make visitors to the bookstore feel as though they are being waited on by an equal…

…

“…the characters in Service are caught in a culture in which people can be reduced to footholds in a lifestyle. In a city—and a century—where all but the extraordinarily rich feel downwardly mobile, we date, fuck, and befriend those we think can help us hold on to who we think we are: a middle-aged man who’s still got it, a woman whose fame means she’s not alone. It’s a grim picture of vanity and masochism, of self-regard so unshakable that there are no depths to which we won’t sink to preserve it. Or, as Sean puts it, ‘You don’t need to have a death wish to live in Los Angeles, but it helps.’”

–Anahid Nersessian on John Tottenham’s Service (The New York Review of Books)

“So long have serial killers been a staple of American popular entertainment…that it’s a welcome reminder in Caroline Fraser’s unrelentingly bleak and impassioned Murderland that not all of them are individuals: ‘Corporations can be people, and people can be killers, ergo, corporations can be killers … The product of vast research into the correlation between violent behavior and neurological damage associated with high levels of environmental pollutants (lead, asbestos, arsenic) in the blood, it is an amalgam of true crime reportage, visionary muckraking in the tradition of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), and a startlingly candid memoir of Fraser’s girlhood in the Seattle area in ‘the time of serial killers’—both individual and corporate. Its theme is simple and terrible enough to be repeated time and again through four-hundred-plus pages: ‘More lead, more murder.’

…

“Though Murderland might be cataloged as ecojournalism, it is also a multi-true-crime narrative related in a breathlessly propulsive manner. Folded into the charges against corporate polluters like ASARCO are passages that fairly spring off the page.

…

“As the chronicler of Murderland Fraser doesn’t identify herself as wholly alien to Bundy et al. in the way that writers usually detach themselves from subjects as horrific as hers. And she doesn’t detach herself from the instinct to kill, not serially but in her girlhood wish to murder her father and, perhaps most surprisingly, her disappointment as an adult that she never did.

…

“The sympathetic reader is inclined to inquire: Why are sexual serial killers the sole concern of Murderland, rather than mass murderers, school shooters, and domestic terrorists, so much more representative of the current violence of the United States? It is likely that gun violence also springs from mental illness or brain dysfunction, whether caused by lead-spewing smelters or hate-spewing right-wing media, not to mention (as Fraser does not) the prevalence in the US of every sort of firearm and ever more lax gun control laws.”

–Joyce Carol Oates on Caroline Fraser’s Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers (The New York Review of Books)

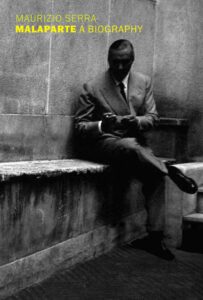

“‘Fascism’ is notoriously difficult to define. It insisted on conformism while attracting bohemians and subversives, fused manic idealism with brutal cynicism and combined elements of modernism and pastoral nostalgia. The critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin once wrote that ‘fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into political life.’ In Malaparte, Maurizio Serra’s outstanding biography of the Italian dandy, journalist, playwright, would-be diplomat and filmmaker Curzio Malaparte, the author makes clear that Benjamin was correct. Whatever else it was, 20th-century fascism was a project more of imagination than reason; it was driven by aspiring European elites who presented themselves as populists in their pursuit of grandeur and greatness.

…

“The sociologist Michael Mann once wrote, ‘Fascism was a movement of the lesser intelligentsia,’ but Malaparte was a first-rate talent as both journalist and fiction writer. Still, he struggled to put his creative energy to constructive use: He looked down on losers, but, in his misbegotten schemes and futile projects, he found himself among their ranks.

There is a pathetic aspect to Serra’s account of Malaparte’s life, a solipsism that despaired of finding anything worthwhile in life other than movement and adventure. The anti-intellectual intellectual, the macho man who wore makeup and sported perfectly coifed hair; physically courageous as a soldier and war correspondent but in politics and his personal life a moral coward; the militant anti-communist fascinated with Lenin’s Russia and, eventually, Mao’s China; the bourgeois snob who hated the bourgeoise and idealized both proletarians and aristocrats: Malaparte embodied, almost perfectly, the contradictory impulses of the fascist generation.

Malaparte was not among fascism’s top ranks. He was not one of the chief ideologues, like his fellow writer Giuseppe Bottai. But, as his literary fame spread during the interwar period, he showed fascism’s seductive side and cultivated a fraught relationship with Mussolini that continued into the 1930s. Malaparte demonstrates that fascism was not only a collective enterprise and cult of the leader, but an individual one: a narcissistic worship of the self and a chance for ambitious young men from the provinces, dissatisfied with their place in liberal society, to embark upon a career.”

–John Ganz on Maurizio Serra’s Malaparte: A Biography (The New York Times Book Review)

“I approached Red Barns gingerly, expecting harrowing descriptions of slaughterhouses and a litany of woes that would flatten me—and possibly, finally, drive me to the veganism I’ve long resisted because of my fondness for cheese.

Such reluctance to engage with the ongoing tragedy of corporate meat production, after all, is the ugly cross that animal rights activists have to bear. Environmentalists advocating for wild landscapes and creatures have breathtaking panoramas and wildlife charisma to help with their public calls to action. Look at this beauty! they can say. Help us save it! But activists trying to put a stop to the heartbreaking misery of animals being raised for food by large corporate entities have no beauty to sell. All they’ve got is: Look at this torture! Most of us prefer not to. Luckily, Little Red Barns isn’t a depressing litany, though it may well change your mind about buying industrial meat.

…

“We tend to take our food for granted, shrugging off the distant unpleasantness of factory farms as the price of a tasty slab of bacon. And yet this food empire isn’t an economic inevitability. It is, Potter explains, a result of a concerted, decades-long campaign by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Congress and their corporate-ag sponsors to consolidate production and squeeze out small farmers (historically, often Black). More recently, it’s the work of a few very, very rich companies. Potter reports that ‘four companies operate about 75 percent of the world’s corporate beef packing plants and abattoirs. Another four control about 70 percent of pig slaughter.’

Even if we put humaneness and decency aside, the climate damage and extinctions being wrought by our funneling of resources into meat—when plant-based foods are both healthier and more efficient at delivering nutrients—mean we have to look far deeper than the Old MacDonald song, with its vanished quaintness, and past the illusive images of cowboy cool that still serve to reassure us that our farms and feedlots are fine places. Let’s tell ourselves the story, Potter writes, that’s true.”

–Lydia Millet on Will Potter’s Little Red Barns: Hiding the Truth, from Farm to Table (The Washington Post)