Do you remember it? When you changed? Or, stranger still, when you were between one thing and another? I do. When my breasts started to show beneath my T-shirt—buds, they called them, but it never felt like a flowering. In the dictionary under buds, it explains: in certain limbless lizards and snakes a limb bud develops. That’s more like it.

Girlhood can be brutal. Your body swells, hair sprouts haphazardly, and then you bleed from between your legs while everyone behaves as if it’s perfectly normal. Perhaps it’s the bleeding that sets the men upon you, like the wolves of fairy tales, because that follows soon after. But there’s power in this new body, too, if you know how to find it.

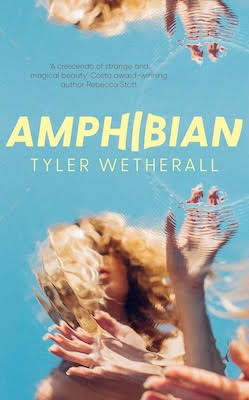

In writing my debut novel, Amphibian, I wanted to conjure a girlhood like this, as I had felt it: hyper sensorial, rich with fledgling desires and fraught with new social rules—and, at times, frightening. My 12-year-old protagonist, Sissy, feels her body changing, except she’s not changing like the other girls. “Puberty is vicious,” her mother says, brushing her worries away. Obsessed with stories of how other women’s bodies have transformed before her, and judged by a chorus of ribald girls in her head, she and her best friend Tegan depart from the make-believe woods of childhood to find themselves somewhere new and terrifying.

Fabulism offered me a vehicle for this feeling—of crossing uncharted terrain. The following list of books, while all literary fiction, also borrow from the toolbox of magic realism and horror to convey the experience of girlhood in all its delight and barbarity.

Chlorine by Jade Song

Ren Yu is a mermaid. She tells you so on the first page. She doesn’t come from the tradition of red-haired shell-breasted singing mermaids; she is ripped, disinterested in humans, particularly men, and, by the climax of the book—she’s bloody. Ren narrates the story of her self-determined transformation starting from her life as a young competitive swimmer, so addicted to the water and the race that she licked the chlorine from her skin when she missed the pool. But as the pressure to win, and to prove herself by getting into an Ivy League college mounts, along with cruelties from her crew of fellow swimmers, she starts to pursue her longing to be a mermaid with a near holy embrace of physical pain.

The Ice Palace by Tarjei Vesaas

First published in 1963, it’s considered a classic of Norwegian literature, but, I find, too few people have read it. Siss, the leader of the pack at school, is fascinated by Unn, the reclusive yet defiant new arrival in their rural community. One night, they share their feelings for each other in a scene simmering with strange tension. The next day, Unn, embarrassed by what passed between them, skips school to visit the Ice Palace, a frozen waterfall in the Norwegian fjords transformed every winter into a fantastical labyrinthine structure. Unn never returns; and Siss is left to make sense of her loss. Fragmentary and hauntingly poetic, the horror here is all below the surface—apt in this world of ice and snow; it’s in the mark on Unn’s body, the mysterious “other,” apparitions and night terrors, and in her secret that’s never told.

Brutes by Dizz Tate

“We would not be born out of sweetness, we were born out of rage,” says the pack of girls (and one queer boy) who serve as our first-person plural narrator for much of the book. They speak and move collectively, as obsessive in their adoration of some as they are wantonly cruel to others: the titular brutes. The swampy Florida town in which these eighth graders live sends its young people into the clutches of a seedy talent scout, one of its Technicolor cast of characters, with the book opening on the disappearance of the famous televangelist’s daughter, Sammy. The narrative occasionally flashes forward to the girls’ adult lives written in the first person singular, to demonstrate how fully the bonds of girlhood can break. But while the story tracks the shocking events of one summer, its preoccupation is elsewhere: in the depths of their loyalty, in the oppressive power of the small town, and in the sinister pull of whatever lurks beneath the surface of the lake.

Cecilia by K Ming Chang

Cecilia was the object of Seven’s obsession during their school days together. When a chance encounter at the chiropractor’s office where Seven works as a cleaner puts the two now adult women back in each other’s orbit, it prompts a stream of sensorial memories for Seven. Unmoored by the power of her past desires, she—and us by extension—loses her grip on the present, flung back to a girlhood full of poetic grotesqueries: eye sockets sucked of their juices, so many slugs, crows everywhere, bodily fluids of every ilk, a breast bitten “off like a bulb of blood,” and a longing so deep and misunderstood that Seven can only envision its fulfillment as violence. This surreal novella packs a punch.

The Seas by Samantha Hunt

“Are you really a mermaid or does it just feel that way in the awkward body of a ‘teenage girl?’” the unnamed narrator asks herself in The Seas. It’s little wonder that mermaids recur on this list, adored by girls for their shimmering beauty and feared in folktales for their untamed sexuality, an apt contradiction. Our unnamed narrator is stuck in a coastal fishing town, sad and outcast, holding vigil for her long-lost sailor father and in love with Jude, an older man returned from the Iraq war broken. She holds onto what her father once told her: that she is, in fact, a mermaid. In prose so wildly original and spare it’s staggering, our narrator falteringly pursues her two passions—Jude and the sea—but as her slippages between fantasy and reality become more frequent, we, too, depart on a different sort of tale.

The Curators by Maggie Nye

Another polyvocal entry, this historical fantasy is told mostly by a group of five teenage Jewish girls obsessed—as was the rest of Atlanta in 1915—with the real life lynching of Jewish factory superintendent Leo Frank for the murder of Mary Phagan. This public trauma is experienced through their adolescent lens, and Frank is mythologized as an object of the girls’ hungry desires. Urgent and lyrical, the novel is as much about this crime—with all its relevance today—as it is about girlhood and the power of devotion. Determined to keep his memory alive, they use dirt from the garden to create a golem in his image, but then––brilliantly––their golem starts to speak.

Jawbone by Mónica Ojeda

The book opens with Fernanda tied to a chair in a cabin having been kidnapped, not by some sinister creep, but by her teacher, Miss Clara. We track back to learn how Fernanda and her best friend Annelise (“the inseparables”) like to gather after school with their six-girl clique in an abandoned building. Here they indulge in humiliating dares, rituals to the rhinestone-encrusted, drag queen God of their imaginings. The novel plays on the line between pleasure and pain, fear and desire—or, in Annelise’s thinking, between horror and orgasm. The tone is ominous, propulsive, and wholly befitting its teen subjects in its fevered twistedness. Of all the books on the list, Jawbone is perhaps most specifically about the horrors of adolescence and how becoming a woman can be a horror story itself.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.