A good book that’s set on a farm can immerse you in an historical epoch, make you laugh until your sides hurt, inspire you to fight for a just cause, or sob over an unjust death. And it can so engross you that by the time you turn the last page, you might be bubbling over with the thrill of knowing just what it takes to grow a crop of sugar cane, or find yourself cheering on the conversion of Great Plains ranches from cattle to bison.

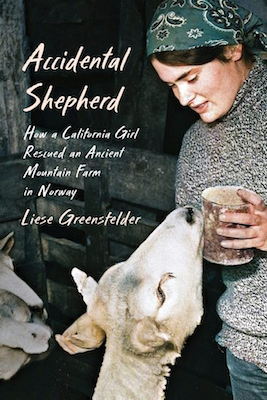

In my book, Accidental Shepherd: How a California Girl Rescued an Ancient Mountain Farm in Norway, I tell how I arrived in Norway in 1972 for a summer job only to learn that the farmer I’d come to work for had just suffered a stroke. I was a 20-year-old girl from California who knew nothing about agriculture, yet two days later I was dropped off on his remote farm at the very end of a three-mile dirt road leading from the magnificent Hardanger Fjord into the mountains. Accidental Shepherd weaves together the stories of my neighbors’ grass-based sustainable farming practices with my yearlong struggle to keep the farm afloat … along with plenty of my adventures and misadventures as I made my way into a centuries-old community of older farmers.

Our culture, history and ancestry are tied to agriculture. Yet in an increasingly urbanized society, most people now know almost nothing about farming. While we might happily disregard our cultural connections to growing food, we are at our peril in underestimating the vital role agriculture plays not just on our appetites, but on our health and well-being, as well. So my two prerequisites for works to include in this reading list were that the writing—whether fiction or memoir—was captivating, and that the real work that happens on farms had been skillfully and accurately woven into the narrative. No matter the crop, herd or flock, while producing the food that sustains everyone, farmers have always faced long days of hard labor, a dearth of free time, and the ever-present threat of catastrophic loss from disease, accident, or freakish weather.

The stories you’ll find in these seven books all ring true, whether illuminating the past or the present, or suggesting a sustainable path forward.

Growth of the Soil (Markens Grøde) by Knut Hamsun, translated by Sverre Lyngstad

“The man comes, walking toward the north. He bears a sack, the first sack, carrying food and some few implements.”

Thus begins Knut Hamsun’s epic tale of Isak, his wife, Inger, and their children, as they mold a tract of forested Norwegian wilderness into a farm to satisfy the universal need for food and shelter. Set in the latter half of the 19th century, the book garnered Hamsun the 1920 Nobel Prize in Literature. This was an unusual move for the Nobel Committee, which generally awards the prize based on the body of an author’s writings rather than a single volume. In making the award, the Committee described this “monumental work” as “an epic paean to work and the relationship between humanity and nature.”

Far more than a narrative about subduing the wilderness, Growth of the Soil is populated with other would-be farmers who push into the land around Isak’s holdings. Some are good neighbors and land stewards, others are prying, lazy and deceptive. Two women commit infanticide, each for their own reason. Inger will spend six years in prison for the crime. While there, she learns how to read and is exposed to a more modern way of life, which changes her attitude about the farm after she returns home. The couple’s two sons struggle with their futures, and head down divergent paths. Yet even as “civilization” encroaches on the farm, Isak continues his work, improving his land as best he knows how.

O Pioneers! by Willa Cather

Willa Cather’s most famous novel is set in the farming region of South Central Nebraska, sweeping through the last two decades of the 19th century and into the first years of the 20th. Her elegant narrative centers on a dispersed community of immigrant families (Swedish, Bohemian, French, Norwegian) struggling to establish homesteads on virgin prairie land, although many have no earlier farming experience.

In the opening chapters, John Bergson, a Swede, is on his deathbed. Although he has toiled for 11 years on his homestead, he has nothing to show for it, viewing his land as “still a wild thing, that had its ugly moods.” Understanding that his oldest child, Alexandra, is smarter and more sensible than his two older sons, Lou and Oscar, he appoints her as administrator of the farm, and directs the boys to heed her guidance.

Sixteen years later, the land has been transformed: “The shaggy coat of the prairie … has vanished forever. … one looks out over a vast checker-board, marked off in squares of wheat and corn … Telephone wires hum along the white roads, which always run at right angles.” On the Bergson farm, Alexandra has made such wise decisions that she now heads one of the largest and most prosperous holdings in the region. But instead of gratitude, Lou and Oscar harbor only resentment toward her. When they suspect she is considering marrying a childhood friend, their true feelings are revealed in an ugly conversation, after which Alexandra cuts off contact with them both.

Meanwhile, Emil, the youngest of Bergson’s four children and the first in the family to go off to college, returns home and falls in love with Alexandra’s closest neighbor, a young and spirited Bohemian woman married to a jealous husband. The book’s tranquil narrative speeds up in the final chapters, as these and other threads come to a head.

For the Hog Killing, 1979 photos by Tanya Amyx Berry and essay by Wendell Berry

In 1979, Kentucky farmer Tanya Amyx Berry had the foresight to pull out her camera on the two long days in November when a group of her friends, family and neighbors came together to slaughter 20 hogs, butcher their carcasses, and process the meat. For the Hog Killing, 1979, contains some four-dozen of Berry’s photographs documenting each stage of these crucial operations.

In a long essay accompanying the photos, Berry’s husband, the renowned author, poet and essayist Wendell Berry, writes, “The traditional neighborly work of killing a hog and preparing it as food for humans is either a fine art or a shameful mess. It requires knowledge, experience, skill, good sense, and sympathy.”

Elegant and engaging, the book is quite possibly the only visually comprehensive chronicle of the decades-old—or more likely centuries-old—community endeavor that Wendell Berry calls “the neighborly art of hog killing.” The Berrys’ slender volume deserves a place on the reading list of anyone curious about mindful and compassionate animal husbandry.

Queen Sugar by Natalie Baszile

This debut novel by Natalie Baszile beautifully weaves the art of growing sugar cane into a gripping narrative packed with a host of captivating characters.

When Charley, a 34-year-old black woman who teaches art to inner-school kids in Los Angeles, inherits an 800-acre sugar cane plantation, she drives with her 11-year-old daughter to her father’s hometown in south Louisiana, determined to learn how to manage the place. Four years a widow, she needs this life-changing challenge and the income it will provide.

Yet upon arrival in the small town of St. Josephine, she finds that the plantation manager is quitting, stunted sugar cane plants and weeds cover her fields, and the farm’s tractors and other necessary equipment are in bad shape or entirely missing. But heading home is not an option, for her father’s will stipulates that if the land is sold, any proceeds must go to charity.

Thus ensues Charley’s battle to salvage the farm. Lodged with her daughter in her grandmother’s ramshackle house, she reunites with a host of relatives and soon finds herself partnering with a black plantation manager considered to be the savviest man in the business, and a white grower who has lost his own plantation to the bank. Over the course of the growing season, she teeters on the edge of losing the plantation, encounters racism both veiled and overt, and must also contend with an estranged and resentful half-brother whose violent outbursts have alienated him from all of his relatives except their grandma. And oh yes, Baszile also blends a thread of romance into her finely-woven tapestry.

Buffalo for the Broken Heart: Restoring Life to a Black Hills Ranch by Dan O’Brien

“Being in good health, and educated to make a living with books, I didn’t have to settle for a job in a gas station or a bar,” writes author Dan O’Brien in Buffalo for the Broken Heart. Instead, in the mid-1980s, he takes out a mortgage on a working ranch in South Dakota, only to find that making a profit running cattle on the Great Plains—or even breaking even—is virtually impossible. Yet he stumbles along until January 1998, when, in the depths of depression, he heads to a distant buffalo ranch to help with its annual roundup.

Despite sub-zero temperatures, every day O’Brien spends with these wild creatures, he appreciates them more and more. By the end of the week, when he overhears two ranch hands wondering what to do with a dozen motherless calves, he impulsively offers to buy them. And from that day forward, not only is he hooked on buffalo but he also champions the argument that the substitution of buffalo for cattle can revert the nearly universal environmental destruction that the latter have wreaked on the Great Plains.

Fortunately for readers, O’Brien writes about his own ranch’s painstaking conversion with his usual sharp wit, deep knowledge of the natural world, and excellent trove of lively and relevant anecdotes.

Turn Here Sweet Corn by Atina Diffley

A paean to organic farming, and a primer on how and why it works, Atina Diffley’s lengthy memoir spans four decades, beginning with gardening as a young girl with her mother in the 1960s to her years working on two of Minnesota’s most diverse and successful organic vegetable farms alongside her husband, Martin.

Between these bookends, Diffley enters into and gets out of an abusive relationship with her first husband after they have a baby girl together. Months after the divorce she and Martin get together and she moves to his farm, which has been in his family for four generations.

Diffley is enamored of working with the soil to grow healthy food. Her detailed descriptions of producing the farm’s organic crops are like love letters to her readers and her cherished fields. But her family’s idyllic life ends when the local school district condemns 20 acres of the farm’s most productive land, triggering a years-long nightmare of encroaching development that they are powerless to resist.

The power, however, lies in Diffley’s telling of this story. No one can read these details without registering that organic farming is inherently better for farmers, consumers and the environment, and that paving over prime farmland is a travesty that will come to haunt us all. But wait. There’s more. After years of searching for and establishing their second farm, the family faces a new threat when a subsidiary of one of the largest privately held companies in the U.S. files an application to run an oil pipeline straight through the Diffley’s flourishing fields. In face of this threat, Anita Diffley marshals all of her resources in a years-long effort to protect her farm and those of every organic farmer in Minnesota.

Pig Years by Ellyn Gaydos

In Pig Years, author Ellyn Gaydos chronicles her work as a farmhand on small vegetable farms in New York and Vermont from 2016 to 2020. The majority of her musings are from a 20-acre organic farm near New Lebanon, New York, where she shares a house with Sarah and Ethan, friends of hers who own the farm, but not the land beneath it.

Thanks to her sharp eye and passion for detailing daily events in her notebook, she has created a volume of … well … not quite stream-of-consciousness musings, but a stream of observations and extended vignettes. She has crafted these so carefully that I was virtually watching her in action as I was reading: there she was driving a decades-old tractor down a vegetable row, gently handling newly harvested cabbages “so full of moisture and nutrient they threaten to split open like melons bursting after being picked,” or just hanging out after work with fellow farmhands in a small-town pizza joint. Equally descriptive—excruciatingly so—are passages about the slaughter of a farm’s old hens and her own three pigs.

The work pays very little. Not just Gaydos and her fellow farmhands, but the farm owners, as well, often seem close to the edge financially. “At every meal, we eat mustard greens,” she writes. “Mustard greens and hot grits. It is early June now, and there is still a feeling of scarcity while we wait for the returns of summer to come in.”

Such observations lend a somber tone to much of the book. And therein lies its power, which perhaps can be summed up when the author ruminates that, “There are things like unintentionally uprooting rabbits’ nests, and orphaning the young of all types of animals, and then there is the task of understanding oneself as arbiter, raising an animal with designs for its death.” And this, indeed, underlies not just agriculture, but our lives as humans.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.