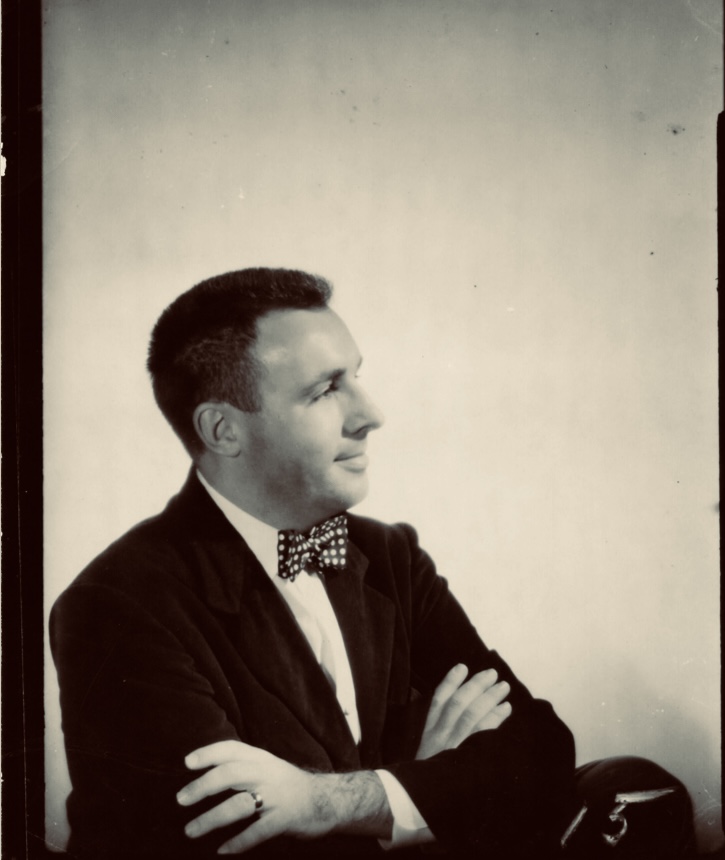

“I recall Midwestern summer nights, standing on my grandparents’ hushed lawn,” Ray Bradbury told me in 2010, “and looking up at the sky at the confetti field of stars. There were millions of suns out there, and millions of planets rotating around those suns. And I knew there was life out there, in the great vastness. We are just too far apart, separated by too great a distance to reach one another.”

For the young Bradbury, who would grow up to make that great vastness feel, to many, as almost as tangible as home, there was one celestial body more captivating than any other: Mars.

Mars: The fourth planet from our sun, some 140 million miles from us on average. The only planet in our solar system, other than our own, deemed by scientists and stargazers over the centuries to be—possibly, at one time—hospitable to life.

The planet has been part of our collective imagination for centuries, from the tales of ancient mythology, to H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, to David Bowie’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders of Mars. Ray Bradbury may have been yet another in a long line of artists dreaming about Mars, but he was the first science fiction writer to elevate the planetary tale beyond the marginalized gutter of “genre fiction,” with his 1950 story cycle The Martian Chronicles.

The Martian Chronicles is a serious book about serious human themes. It is science fiction as a reflection of modernity.

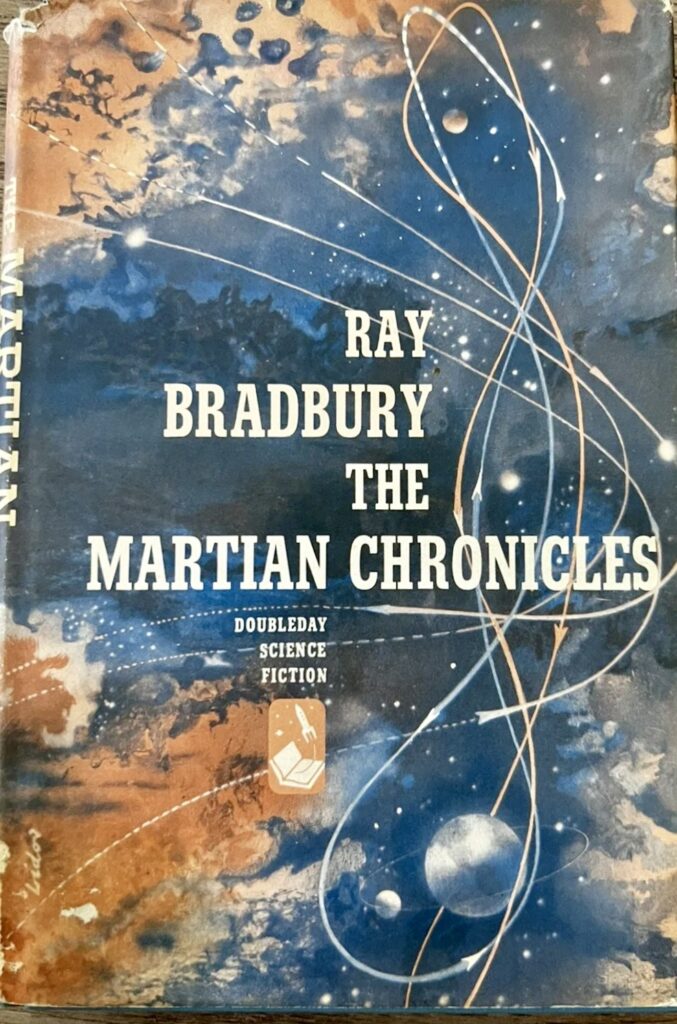

While Bradbury’s 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451 is often cited as his crowning achievement, it was The Martian Chronicles—arguably a superior work—that put his name on the literary map. The Martian Chronicles was published by Doubleday 75 years ago, on May 4th, 1950. Until that point, science fiction had been mostly dismissed by the firmament as “kids’ stuff,” littered as it was with pulpy tropes such as ray guns, little green men, and scantily clad damsels in distress. But The Martian Chronicles subverted all that, addressing a range of vital, vexing, timeless societal themes in the midst of McCarthy era America: nuclear war, genocide, environmental destruction, the rise of technology, corporatization, censorship, and racism.

Lamentably, these themes still tower over us in the Trumpian zeitgeist all these years later, but their continuing relevance only underscores the point: The Martian Chronicles is a serious book about serious human themes. It is science fiction as a reflection of modernity. The writing is exquisite, showcasing Bradbury at the dizzying height of his poetic prowess, lyrical, rich in metaphor, pastoral, with stunning passages of seemingly effortless prose, eschewing the occasionally purple passages of certain other works, like Something Wicked This Way Comes, and the more dialogue driven polemics of Fahrenheit 451. It hits the sweet spot between poetic exposition and complete narrative originality. With its publication, Ray Bradbury, not quite 30 years old, had pulled off a tour de force magique—he had created literary science fiction, and the intelligentsia quickly took notice.

The Martian Chronicles was, in some ways, a book Bradbury was always destined to write. His childhood was awash in stories of the fantastic. His mother took him to the Elite Theatre to see The Hunchback of Notre Dame, starring Lon Chaney, when he was three. At five, he was completely enthralled by The Phantom of the Opera. His Aunt Neva, ten years his senior, introduced him to the Oz books by L. Frank Baum and to the wicked tales of Edgar Allan Poe. He followed Philip Francis Nowlan’s Buck Rogers comic strips religiously in the Sunday Chicago Tribune. In 1930, already in love with books, Bradbury discovered A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs on his Uncle Bion’s shelf. He was engrossed. It was Burroughs’ books that first transported him to Mars.

In the fall of 1932, like so many families, the Great Depression devastated the Bradburys. Ray’s father Leo, a utility line worker, found himself unemployed. Looking for a brighter future, they packed the family Buick and rumbled down Route 66. They arrived in Los Angeles, where they had family, and where Bradbury would live out the rest of his life (he passed on June 5, 2012). But the Midwest had already seeped into his DNA. The Martian Chronicles is certainly awash in the heartland and its sensibilities.

The first rockets blasting off from earth in the opening story, “Rocket Summer: January 1999,” leave from Ohio. In “The Third Expedition: April 2000” (originally titled “Mars is Heaven”), the small town with its tidy white houses, leaded glass windows, and potted geraniums discovered by the arriving astronauts is quintessentially midwestern. Of course, the story takes a twisted turn when the astronauts discover what they believe are their deceased loved ones, waiting there to welcome them.

While his formative years in Illinois imprinted on much of his oeuvre, moving to Los Angeles gave Bradbury’s early love for science fiction a safe place to flourish. In the fall of 1937, his senior year at Los Angeles High School, he noticed a flier in a secondhand book shop for “The Los Angeles Science Fiction League,” a meeting of nerds, geeks, creative miscreants, and established writers in the field who met every Thursday evening downtown at Clifton’s Cafeteria. Among this group was Forrest J Ackerman, who would later invent the term “Sci Fi” as a play on “Hi Fi,” and then go on to become the publisher of Famous Monsters of Filmland. Ray Harryhausen, future godfather of Hollywood special effects, was a member, as was successful author Robert Heinlein, and scores of others, including L. Ron Hubbard and Anthony Boucher, who attended sporadically.

Bradbury had found his people. “I couldn’t believe there were so many weirdos just like me,” he said in a 2003 interview with me at his home. During my time working as his biographer, he repeatedly called the group his “ad hoc church.”

Heading home by bus, literally traveling through the dust bowl, he read [The Grapes of Wrath]. As he read, he thought about one day using the same architecture, but setting his story on Mars.

In the summer of 1939, the First World Science Fiction Convention (a precursor to today’s pop culture nerdchellas) was held in New York City. Bradbury was there, alongside editors, agents and writers like Isaac Asimov and the godfather of the Golden Age of Science Fiction, John W. Campbell. Bradbury was one of the youngest of the pack, eager to the point of being a vociferous nuisance to the more established attendees. After the convention, travelling home by Greyhound bus, he made a stop in Waukegan to visit extended family and friends. It was during this brief visit that he would make a prophetic acquisition. In the storefront window of the United Cigar Store, he saw John Steinbeck’s newly published novel The Grapes of Wrath and purchased it.

Heading home by bus, literally traveling through the dust bowl, he read the book. He was particularly drawn to its structure, with its alternating narrative chapters and brief, intercalary passages of contextual information, setting, and social commentary. As he read, he thought about one day using the same architecture, but setting his story on Mars.

In 1940, with Heinlein’s help, Bradbury published his first professional story, in the Los Angeles-based magazine Rob Wagner’s Script, which aspired to be a west coast New Yorker. From then on, throughout the first half of the 1940s, he steadily ascended the hierarchy of writers in Weird Tales. Because of the richness and elegance of his prose, he was deemed “the poet of the pulps.” His name regularly appeared on the cover.

Bradbury always read outside of his field, reading the canon but, more importantly, contemporary literature. He read Eudora Welty, Willa Cather, Katherine Anne Porter, John Steinbeck, and Ernest Hemingway. He stopped reading pulp magazines even as he was gaining prominence in them. The result was that his own writing was not derivative of others in his genre, but was rather born of literary fiction. In 1944, one his mentors in the Los Angeles Science Fiction League gave him a copy of Sherwood Anderson’s 1919 classic, Winesburg, Ohio: A Group of Tales of Ohio Small-Town Life. Bradbury made a note to one day write a series of loosely connected stories in the same way as Anderson, but set the book not in Ohio, but on the Red Planet. Edgar Rice Burroughs, John Steinbeck, Sherwood Anderson: the influences were beginning to pile up.

In his Martian stories, Bradbury was ruminating on social degradation, the search for identity, race relations, and the destructive potential of technology.

The 1940s marked one the greatest periods of growth and maturity of Ray Bradbury’s storied career. He was summoned by the draft board in 1942 and, after his physical, listed as “4-F”—physically ineligible. Without his glasses, he was as good as blind. So he contributed to the war effort by writing promotional copy for the Red Cross, while simultaneously continuing to publish his outré, twisted, and decidedly original stories—some weird fiction, some sci-fi. On December 23, 1943, he sold his first Martian story, “The Million Year Picnic,” to Thrilling Wonder Stories for $32. The story follows a family fleeing an Earth that has been destroyed by war and atomic weapons. (Ironically, this first Mars story would later become the final tale in The Martian Chronicles.)

But he had become a writer of many hats. His “weird,” gothic fiction was largely focused on grief, loss, paranoia, nostalgia and fear. In his Martian stories, Bradbury was ruminating on social degradation, the search for identity, race relations, and the destructive potential of technology. At the same time (1945 and 1946) he donned a third authorial identity, as realist contemporary prose writer, breaking into slick magazines such as American Mercury and in 1947, The New Yorker. His story “Powerhouse,” a Zen-like existential musing on the connectivity of the human experience, was published in Charm in 1948, and landed in the Best American Short Stories of the Year, the preeminent anthology of short literary fiction.

Even as Bradbury was embraced by the New York cognoscenti—traveling to the city in the fall of ‘46, drawing the attention of Truman Capote, meeting Gore Vidal, dancing with Carson McCullers at a Manhattan party—Mars beckoned. Yet he would not dare tell his New York associates, for fear of being laughed out of the room.

Bradbury’s first book, Dark Carnival, a collection of 27 tales of the supernatural and the strange, was released by the small Wisconsin-based publisher Arkham House in April of 1947. But he continued to quietly write and publish his Mars stories.

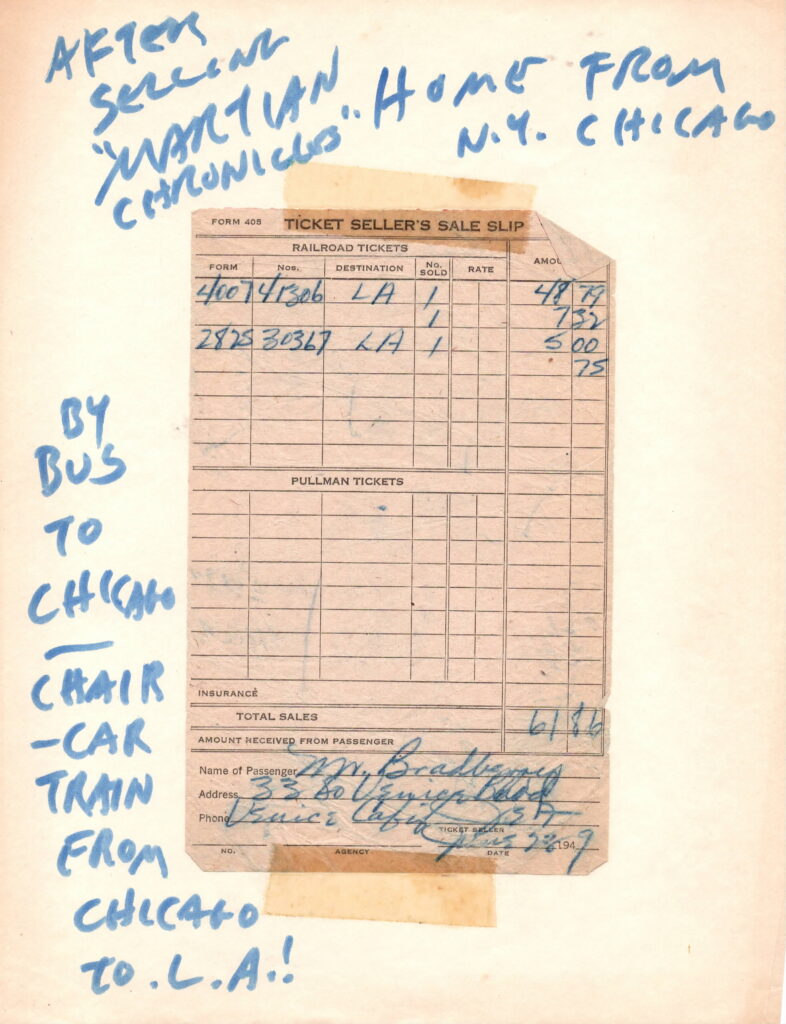

In 1949, when Bradbury’s wife was pregnant, and he was desperate to sell a new book to keep income flowing in, his friend and mentor Norman Corwin advised Bradbury to go back to New York to make face-to-face connections with publishers. Bradbury did just that. To save money, he travelled by Greyhound bus and stayed at the Sloane House YMCA on West 34th Street for $1 a night. He made the rounds to the publishing houses, pitching a collection of short stories. But no one was biting. Publishers wanted a novel or nothing.

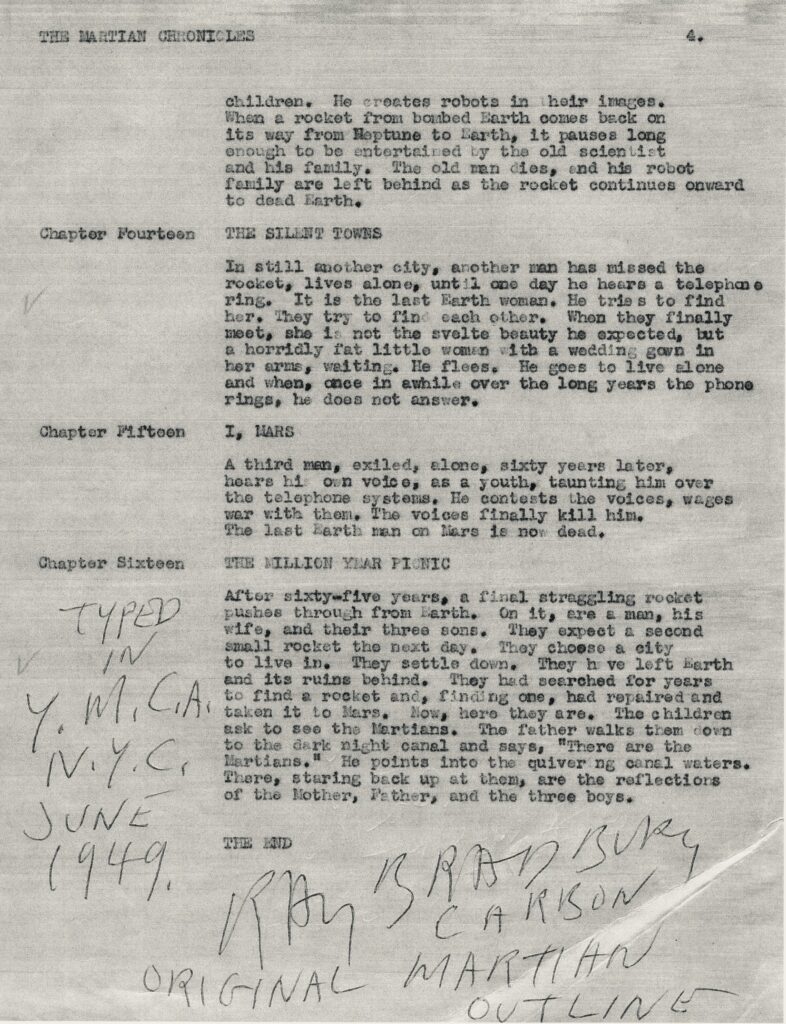

On his final full day in New York City, Bradbury dined at Lüchow’s, a German restaurant and cultural hub in Union Square, with Doubleday editor Walter Bradbury (no relation). It was Walter who brought up the subject of Ray’s Martian stories, and suggested he might connect them into a makeshift story cycle. He asked Ray to put a quick outline together before he headed back to Los Angeles the next day.

Bradbury returned to Sloane House. It was a sweltering evening and the facility was without air conditioning. He sat in his underwear and t-shirt at his portable typewriter and hammered out a four-page outline, loosely connecting his Martian stories, and recalling the intercalary chapters in The Grapes of Wrath. In his outline, humankind colonized Mars, and Bradbury saw a parallel to the history of American Westward expansion.

“I decided,” Bradbury wrote in the unpublished (save for a pricey 2008 edition of 1000 copies) essay ‘How I Wrote my Book,’ dated October 17, 1950, “there would be certain elements of similarity between the invasion of Mars and the invasion of the Wild West in the years from 1840 to 1900. I had heard from my father’s lips, and my grandfathers [sic] stories of varied adventures in the West … when things were empty, still, and lonely … So I knew that Mars, in reality, would be that new horizon that Steinbeck’s Billy Buck mused upon when he stood upon the shore of the Pacific and the ‘Going West’ was over.”

The book’s structure came together in one white hot night at a YMCA in New York City. Bradbury, without notes or files, recalled all of his Martian stories and used them to construct a linear narrative of interplanetary colonization.

The next day, he presented his outline to Walter Bradbury, who was sold. He offered Bradbury a two-book contract, $750 for the Mars book, and $750 for his short story collection that would later become 1951’s The Illustrated Man.

After returning to Los Angeles—splurging on a train from Chicago in celebration—Bradbury used a small space in the corner of his parent’s Venice Beach garage as an office space. He rewrote his Martian tales to fit his new chronological colonization concept. He added new stories, and wrote his Steinbeck-esque bridge chapters.

The final stories show remarkable thematic range. “Ylla” concerns an indigenous Martian woman who dreams of a white man arriving on Mars by rocket, causing friction in her marriage. In “Usher II,” an homage to Edgar Allan Poe and a thematic precursor to Fahrenheit 451, a man is angered by censorship of fantasy and science fiction stories back on Earth, so he constructs a replica of Poe’s House of Usher on Mars to murder inquisitive government censors who come knocking. Then there is the literary classic, famous for its lack of human characters: “There Will Come Soft Rains,” in which an automated house on a destroyed Earth goes through all its daily machinations, with no one left to serve.

As Bradbury worked on the stories, his pregnant wife Maggie retyped and assembled them into a polished manuscript. They were an indomitable team. Ray and Maggie Bradbury welcomed their baby daughter, Susan Marguerite, November 5, 1949. The Martian Chronicles was published in May 1950.

Shortly thereafter, Bradbury was in a Santa Monica bookshop doing what most authors secretly do: clandestinely moving his new books to the front store displays for better exposure. That’s when he noticed Christopher Isherwood, famous author and critic, browsing the stacks. Bradbury hastily inscribed a copy of The Martian Chronicles and introduced himself to Isherwood. The other writer was standoffish. Bradbury was yet another young writer pushing yet another new book.

“I hope you like it,” said Bradbury, earnestly.

Several days later, a phone call came. It was Isherwood. “Do you know what you’ve done?” he asked. “You have written a fine book.”

Isherwood had recently been named the literary critic of Tomorrow magazine and told Bradbury with glee that the first book he would review would be The Martian Chronicles.

When the review appeared in Tomorrow in October 1950, the praise was rapturous, noting how Bradbury had completely revitalized what had often been considered a genre for perpetually pubescent men.

“Instead of the grunts of cowboys and the fuddled sexual musings of half-plastered private detectives,” Isherwood wrote, “we are offered adult speculation about the dangers of galactic imperialism and the future of technocratic man.” The review went on: “This is not to suggest, however, that Ray Bradbury can be classified simply as a science-fiction writer, even a superlatively good one.” Instead, “he might be called a writer of fantasy, and his stories ‘tales of the grotesque and arabesque’ in the sense in which those words are used by Poe. Poe’s name comes up, almost inevitably, in any discussion of Mr. Bradbury’s work; not because Mr. Bradbury is an imitator (though he is certainly a disciple) but because he already deserves to be measured against the greatest master of his particular genre.”

This review legitimized science fiction for the first time. The field had grown up and the literary establishment was taking notice.

According to Dana Gioia, former chair of the National Endowment for the Arts and former California poet laureate, Bradbury’s work also had a significant impact on the culture at large. “If you compiled a list in 1950 of the biggest grossing movies ever made,” he told me in 2020, “it would have contained no science fiction films and only one fantasy film, The Wizard of Oz. In Hollywood, science fiction films were low-budget stuff for kids. The mainstream market was, broadly speaking, “realistic”—romances, comedies, historical epics, dramas, war films, and adventure stories.”

“If you look at a similar list today, all but three of the top films—Titanic and two Fast and Furious sequels—are science fiction or fantasy,” Gioia added. “That is 94 percent of the hits. That means in a 70-year period, American popular culture (and to a great degree world popular culture) went from “realism” to fantasy and science fiction. The kids’ stuff became everybody’s stuff. How did that happen? There were many significant factors, but there is no doubt that Ray Bradbury was the most influential writer involved.”

The Martian Chronicles changed the critical view of science fiction, but ironically, the book’s author didn’t consider the work to fit into the genre. “Science Fiction is the art of the possible,” he told me several times over our years working together. “Fantasy is the art of the impossible.”

With blue hills and a breathable atmosphere, canals straight from the visions of 19th century astronomer Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli, and the ruins of ancient Martian cities, Bradbury’s Mars is decidedly and totally imagined. It is emphatically a work of “Fantasy.” Yet, as with his visionary 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury did predict the future with his Martian masterpiece. Just seven years after its publication, on October 4, 1957, Russia launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite into orbit. The space race had begun, and Mars had become just a little bit more possible.