I have a soft spot for ghosts. I see them as a re-emergence of that which has been repressed, their hauntings as a return of the past, either in quiet encroaching or in violent invasion into the present. So restored, the exiled can be either re-integrated or banished, suppressed again. It can also, as it sometimes happens with queer things, and the word itself, be reclaimed. My relationship with the idea of reclaiming is somewhat uneasy because, at least on the surface, it rests on a history of violence that becomes definitionally inescapable: to recast something as benign or even empowering, you first need to have been abused with it. The reclamation is a disarming, a transfer of the weapon from the hands of the oppressor into the hands of the oppressed, where it can, hopefully, be put to better use. The idea is enticing, if vaguely alarming. Ghosts function similarly in making the invisible visible; holding on to the violence done to them, they force a reckoning.

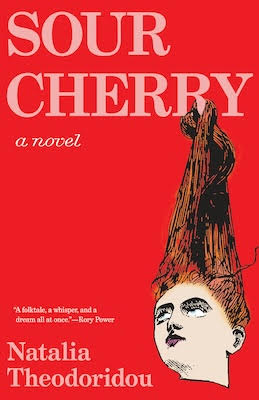

Domestic abuse, especially in queer relationships, has been historically such an invisible thing—threatening, even, to our narratives of feminist empowerment or queer liberation. I am haunted by so many stories of what abuse and violence look like, feel like, sound like; of who can be a victim of these and who a perpetrator; of who can survive them, and how. Is there anything here I’d want to reclaim? Domestic violence is a haunting in that its structures are always already in place thanks, in part, to the stories we tell about it, that we’ve been telling about it for millennia. In Sour Cherry, my debut novel, I chose to retell the story of Bluebeard not in reclamation but in proliferation. The ghosts are many, and they demand their stories told; if not their real ones, then at least the ones you already know.

The queerness of the book is sometimes overt, but usually it is subtle; I find it in the peelings of wallpaper, in the silent longing, in the camaraderie of ghosts. It is also in the dialogue with what came before—because to speak is to invite, to converse is to desire. So here are some books I hope my novel is in conversation with, desiring of, haunted by. These works speak to how hauntings and ghosts can become vehicles for identity-related anxieties, as well as for the unspoken and unspeakable violence and abuse faced by our LGBTQ+ community, and sometimes perpetrated within it. To summon queer ghosts is to counter queer invisibility; to speak of them, with them, through them, is to invent a language for what was before abject and inarticulable.

Bury Your Gays: an Anthology of Tragic Queer Horror edited by Sofia Ajram

Audacious, thought-provoking, and very, very queer, this anthology is as devastating as it is affirming. Here, queer people are afforded the full breadth of human (and sometimes inhuman) complexity. Among these tales you will find a haunted porter of a sentient hotel, a queer kid who makes friends with a telepathic mummy, a serial killer falling in love with a walking corpse; violent delights and parasitic wonders by a host of exciting queer voices, brought together by Sofia Ajram’s dark vision.

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

A memoir about domestic abuse in a queer relationship, pieced together through an intricate overlapping of genres, tropes, and fairy tale motifs. I love everything Machado writes, but what I love in this book in particular is something that had always felt true to me: the conceptualization of intertextuality as haunting. Text, reader, and author are all haunted by the literary corpus that produces us. The book reads me as I read it, and that’s just the way I want it.

Nothing but Blackened Teeth by Cassandra Khaw

This is a novella, creepy and delicious like everything written by Khaw. A group of friends unite to celebrate the wedding of Faiz to Nadia, who has always wanted to get married in a haunted house. The house, a Heian-era Japanese manor, is haunted by a dead bride and the dozens of girls built into its walls. But the real haunting is, as in most of my favorite ghost stories, internal: the characters act out their resentments and dysfunctions with the diligence of ghosts compelled to repeat their pasts and carry out their grudges, inescapably, forever. The past is present, our tiny lives so flimsy we never even stood a chance.

The Thirty Names of Night by Zeyn Joukhadar

A trans boy is haunted by the ghost of his mother, haunted by birds and names, haunted by his own body and a gender that isn’t. A book that resonates with the stories of the past, with longing, with art and all its treasures and losses. This is a jewel of a novel about family and community, and about queers finding joy without denying their pain. Because joy and pain are not opposites; that is a lesson only the most beloved of ghosts can impart.

Homesick by Nino Cipri

This is a collection of weird, deeply moving stories populated by queer and trans characters that find themselves out of place. Jeremy has a poltergeist in his closet, unraveling his clothes (and, let’s be honest, don’t we all?); a team of murdered girls fight “monsters and undead menaces;” and—my favorite—Clay is haunted by keys that show up in his throat while ghosts roam the world. Cipri’s fiction is intelligent, irreverent, tender, and strange in the best of ways.

White Is for Witching by Helen Oyeyemi

I read this book years ago, yet it remains one of my most memorable reading experiences. Both lyrical and horrifying, the novel revolves around a group of women haunted by their racist house. Miranda communicates with the ghosts of her mother and grandmother, but this seems to me the least of her hauntings: her body craves chalk, craves the Silver house, craves her girlfriend. She is a woman riddled with desires that seem forever unfulfillable. Both timeline and point of view feel faltering, stumbling, which, to me, creates the sensation of a slow, protracted suffocation.

Tell Me I’m Worthless by Alison Rumfitt

I have been describing this novel as a book about a haunted house that is also the fascist heart of Britain—and in that way it seems to be in conversation with White is for Witching, too. There are queers in it. There are trans people in it who are neither monsters nor saints, but actual humans who can both hurt and be hurt. (This, in times of moral panics and virtue signalling, is actually refreshing.) There are TERFs (and some of them are human too). There are many things in it that could use content warnings (as there are in life). This is a book that captures something incredibly hard to explain about what it’s like to live as a trans person in the UK right now; it does so with a fierceness and rawness and tenderness that tore me apart (and I was grateful for it). The most heart-wrenching, brutal, and intoxicating book I’ve read in a long while.

Rakesfall by Vajra Chandrasekera

How can I describe this book? It’s by far one of the most inspired and inspiring works I’ve encountered. It starts with a film watched by an audience of ghosts, the spirits of people who have died “hundreds of thousands of times, whether in war, under war, or astride war; in shootings and bombings and shellings and camps and pogroms and hospitals.” The book is made up in part from pieces that have appeared before elsewhere, which is only fitting: the novel is haunted by short stories that had always already been a novel in progress, a book in hiding, sticking out its ghost tongue. Is it queer? Why, yes, of course. Queer as in strange, queer as in gay, queer as in brilliant.

The post 8 Books About Queer Hauntings appeared first on Electric Literature.