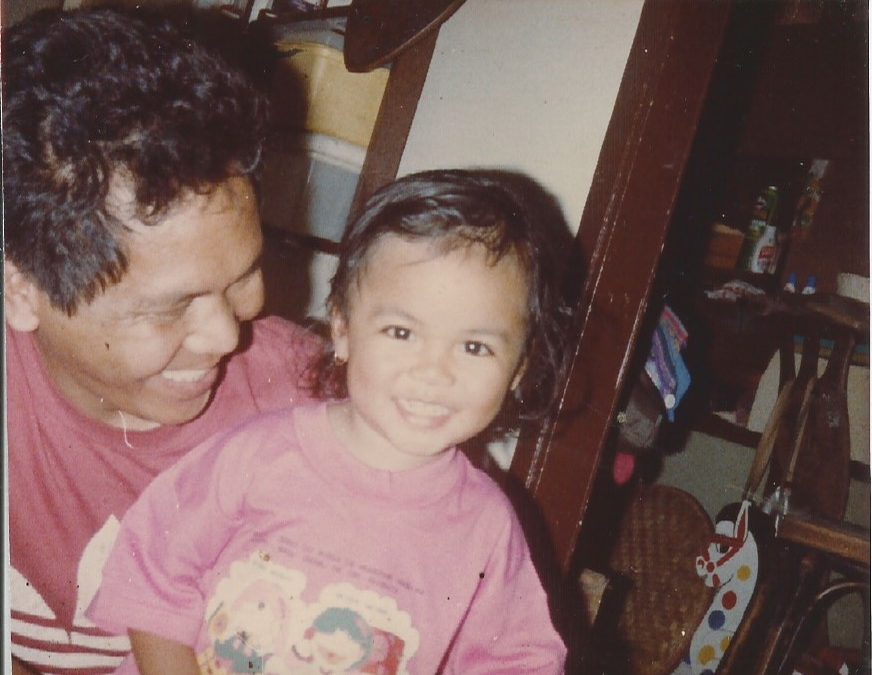

While writing my memoir-in-essays, Returning to My Father’s Kitchen, I sometimes found myself pondering over how fathers are depicted in Filipino books and movies. A harsh, distant, unforgiving father came to mind when I thought of the archetypal Filipino padre de pamilya. This didn’t quite align with my own father’s approach to fatherhood: my father was warm, nurturing, and unguarded, a far cry from the authoritarian figures I’d come to know from Filipino movies and TV shows.

When writing the essays that are now part of Returning to My Father’s Kitchen, I sought to challenge the stereotypes of Filipino fatherhood and manhood reinforced by the media and popularized in public discourse. Not only did my father challenge stereotypes with his style of fatherhood, but he also set an example for me as I pursued the life of an artist. He was a poet who nurtured my literary gifts, and his faith in the life path I chose enabled me to withstand the various challenges that writers face in a society that places little value in the arts. Literary fiction and nonfiction enabled me to explore the complexities and contradictions of the Filipino fathers I knew, which is why I gravitated towards the written word when seeking examples of Filipino fathers that my own work could respond to and be in conversation with.

It was when I began to think back on the books I had read featuring Filipino fathers that I saw how varied and complex their depictions are in literature. While conforming to Philippine society’s expectations of manhood and fatherhood, they also question and even subvert these expectations with their individual actions. Below are nine books that shed light on Filipino fatherhood, presenting us with complex and layered characters whose struggles invite us to perform a closer examination of Filipino masculinity.

Ilustrado by Miguel Syjuco

There are two fathers in Miguel Syjuco’s sweeping 2010 novel Ilustrado: the protagonist’s biological father, a corrupt career politician who expects his son to follow in his footsteps, and Crispin Salvador, a Filipino novelist based in New York who serves as the protagonist’s second father, setting a more positive example for the protagonist as he strives to extricate himself from his powerful family’s tainted history. These two father figures serve as models for what the country’s leaders could be: men who look to the past as they reinforce the ingrained corruption of Philippine politics, and men who hope to break this cycle by exposing the sins of the past.

The Diaspora Sonnets by Oliver de la Paz

In his National Book Award-longlisted collection, The Diaspora Sonnets, de la Paz turns a sympathetic eye on his immigrant father, who attempts to make a clean break with his past while navigating a strange new land with his family. The silence with which his father chooses to enshroud his past becomes a burden in itself, weighing down on his family as they follow his lead into an unchartered future: “Where/there are memories, he lets the splinters/of those shards bury themselves deep into//skin. Where there’s a past, he lets it drive nails/into a tongue he holds back. Father, speak.” Despite these silences, de la Paz refuses to underestimate his father’s inner life, pondering over his father’s reasons for holding back as they provide possibilities for reconnection.

Love Can’t Feed You by Cherry Lou Sy

In Cherry Lou Sy’s coming-of-age novel, Love Can’t Feed You, the protagonist’s father, an elderly Chinese-Filipino man, finds himself adrift when the family lands in Queens and his much younger wife, who immigrated a few years before, immediately puts him to work as a janitor to pay off their debts. Papa reacts violently to his wife’s newfound power and to his diminished role as a new immigrant. His behavior toward his children is oftentimes immature and cruel: in one chapter, he steals money from his own daughter to buy a gift for his wife. His character is an interesting study of fragile masculinity, and the struggles Filipino men face when adjusting to immigrant life.

The Body Papers by Grace Talusan

In her memoir The Body Papers, Grace Talusan reflects on the difficult decisions her father faced to give his family a better life. From choosing to remain in the United States after his medical residency ends, to making the heartbreaking decision to cut off his own father to protect his children, Talusan’s father is complicated but resolute, firm in his attachments to an old way of life, but also brave in defying his culture’s expectations when the occasion warrants it.

Abundance by Jakob Guanzon

Jakob Guanzon’s novel Abundance is a tale of two fathers: the protagonist’s father, a Filipino academic who comes to America for graduate school, only to drop out of his doctoral program and slide into blue collar work to support his family, and Henry, his son, whose feelings of alienation gradually lead him down a life of crime, and who only begins to understand his father’s struggles when he becomes a father himself. Both Henry and his father struggle with fatherhood: Henry’s father responds with violence to his son’s failings in school and in life, while Henry finds himself raising a hand with his child during a particularly low point in his life. Their stories run parallel to each other as they grapple with a sense of inadequacy, borne out of their struggles as immigrants, that taints their relationships with their children.

In the Country by Mia Alvar

The fathers in Mia Alvar’s story collection, In the Country, run the gamut of character types, from being distant and abusive, to having a little selfishness mixed in with their selflessness. My favorite fathers in the collection are Andoy in “A Contract Overseas” and Jim in the titular story, “In the Country.” Working-class Andoy gets his girlfriend pregnant by accident before deciding to find work in Saudi Arabia, joining an exodus of Filipino men who eagerly take on blue collar jobs in the Middle East to support their families back home. Young and naïve, he continues to pine for romance and adventure amidst the drudgery of his work, even when his pursuit of romance turns dangerous. Jim, like Andoy, is an idealist, criticizing the Marcos dictatorship in articles that land him in prison and force him to spend years away from his growing son. Believing that his activism can pave the way for a democratic revolution in his country, and a better future for his children, he ignores the practicalities of raising a family in an authoritarian society, and brushes aside warnings that his writing can put his family in danger.

Forgiving Imelda Marcos by Nathan Go

Nathan Go’s debut novel, Forgiving Imelda Marcos, opens with Corazon Aquino’s chauffeur, Lito, as he drives her from Manila to the mountain city of Baguio to secretly meet Imelda Marcos. At the heart of this novel, however, is Lito’s difficult relationship with his son, who grew up without a father while Lito worked overseas to support his family. Mostly told from the point of view of Lito’s son, Forgiving Imelda Marcos sheds light on the difficult choices that working-class Filipino fathers face: either stick with a low-paying job that does not pay enough to feed, clothe, and educate one’s children, or go overseas for better-paying work, sending money back home while parenting one’s children from afar.

How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo

Castillo begins her essay collection How to Read Now with a tribute to her father, a security guard who maintains a lifelong love for the classics of European and British Literature and passes this on to his daughter. While reading the introductory essay to the book, I was reminded of my own father who also had to take on blue-collar work when we spent time in the United States, while actively maintaining his love for literature and art to preserve his dignity and self-worth. Castillo’s father is a warm and nurturing presence in her life, proving that a life of the mind gives us the strength and vulnerability to be fully present for our children.

Snail Fever: Poems of Two Decades by Francis C. Macansantos

In my father’s fourth and final collection of poetry, he contemplates his complicated relationship with his father, a task that becomes less difficult for him after he himself becomes a father. In “Fisherman’s Sonnet,” he looks back on his father’s attempts to connect with him that he refused to reciprocate because of his father’s physical and verbal abuse, while in “Via Air,” he meditates on the wordless love they shared that finds articulation after his father’s death. In “For My Daughter’s Birthday,” he asks his young daughter to guide him down the mysterious and mystical path of fatherhood. There’s a sense of wonder in my father’s poems about fatherhood as he reckons with his own limitations while extending grace to his father, and to himself.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.