My favorite way to experience a long poem is to listen to it. Because while your body is busy walking or using the elliptical machine or folding piles of blue jeans and t-shirts and pajamas, a voice is laying, like garlands, rings of thoughts and images around your mind, layering a place for you to wander.

It’s the digressions in a long poem that I love—the apertures, structural fractures, pockets, and tunnels. The trap door dropping you down into a dungeon; the stairs leading you out. Poe—whom I adore— argues in The Poetic Principle that poetry should have unity and this unity is impossible in a long poem; but it’s the disunity that attracts me.

I once knew a man who worked in Mission Control at NASA, and he explained to me that his job was to do the math calculations required to keep the International Space Station in orbit. He used the metaphor of balancing a broom vertically in the palm of your hand: his work was like the infinitesimal or large movements to keep the broom aloft. I love that tension in a long poem, the way it’s always threatening to crash down, peter out, rupture, or break; I love the ways the author then invents shapes to keep the thing aloft, to account for shifts and junctures, the unity in the disunity.

My new book, Rich Wife, is composed of long poems because the form is capacious. Registers shift; perspectives shift; the form can undulate from a list to a quote to a description of a memory or a painting. Montage, collage, dialogue, slang, poems within poems. The long poem allowed me to consider a knot of topics—money, beauty, art—with the fullness that the subjects demand.

And on to my recommendations.

Poemland by Chelsey Minnis

A book-length musing about poetry and its glittering potentials and failures, this poem consists, almost exclusively, of aphorisms, metaphors, absurd jokes, and idiomatic turns of phrase… Reading Poemland is like walking around the set of a film you love, sitting in actual chairs which are also pretend chairs, being in a place that exists but does not exist, tawdry but imbued with shared feelings of longing. Her writing is like fake fur, the color chartreuse, a miniature weapon hidden in a vintage snap-clasp purse. Charming and pouty, it reminds me of the feeling of reading a glossy fashion magazine while lying on your stomach in your childhood bed. It reminds me of those girlish leather diaries that have DIARY written across the front in script, and come with a tiny padlock and a tiny set of keys.

The book opens:

This is a cut-down chandelier…

And it is like coughing at the piano before you start playing a terrible waltz…

The past should go away but it never does…

And it is like a swimming pool at the foot of the stairs…

Nature Poem by Tommy Pico

The second book-length poem in a series of four book-length poems, Nature Poem is an argument, a conversation, a soundtrack, an endless scroll. Taking up the problem of both wanting to write a nature poem and not wanting to embody stereotypes about American Indians, Pico ends up writing a book that circles and weaves a complex response, encompassing feelings and ideas as large as the poem itself, impossible to distill. Reading this poem is like watching a virtuosic dance performance, as Pico shifts tones, employing lists, refrains, anaphora, epistrophe, jokes, puns, personification. Like Minnis’s poem, this poem too is about poetry itself, its limitations and magic. Nature Poem delves into romance, identity, pop culture, city life, and death, returning again and again to the premature deaths of cousins back home. Pico creates a place where meaning and emotion can stream back and forth intelligibly among this chaotic, fragmented world we share.

the fabric of our lives #death

some people wait a lifetime for a moment like this #death

reach out and touch someone #death

he kindly stopped for me #death

kid-tested, mother approved #death

oops, I did it again #death

it keeps going, and going, and going #death

Tender Data by Monica McClure

The center of Tender Data contains a group of longish poems that were originally published as the chapbook Mala. These slender montages bring together the feelings of being a girl — being looked at, looking at yourself as an object, longing, desire, innocence and its loss, the narrow roles family and society present for you. Childhood scenes are spliced with older perspectives, with metatextual analysis of the poem as poem, critical analysis of how she’s positioning herself, resisting received categories. These poems juxtapose small town aspirations and gossip and poverty and glamour and grocery store aisles and slips of admonishments and slang. Climb inside these poems to become a girl in the early 2000s, in body and spirit, to experience the liquid confusing swirl.

Let’s talk about angels

I saw one just returned from jail with his gentleness

flung over the couch next to his money stack

We didn’t know each other anymore

and never had

We were standing beside our youths like babysitters

But the truth is I was the only one who’d ever had one

Bloom & Other Poems by Xi Chuan, translated by Lucas Klein

In his longish, essayistic poems in this book, Xi Chuan takes up a subject — the mandate to bloom, beautiful fakes and decrepit antiques of the Panjiayuan Antiques Market, an early morning, Manhattan — and he approaches it from in front, beside, below, near, far, with humor, with humility, with cynicism, with history, with literary forefathers, with grandiosity, turning and turning until the subject is exhausted thoroughly, until we, having journeyed and arrived together, land at the poem’s feet. Xi Chuan takes up what could seem the least promising of subjects—just walking around, looking around—and with the force of his intelligence and the shape of his thoughts wrings from them meditations which are surreal, self-deprecating, self-aware, often recalling, too, the long history of poetry, art, and politics of China, people from the past peering across time into the present, and he peering back at them.

People half real half fake pursue a happiness half real half fake,

fall in love half real half fake, and fall into a daze looking at half real half fake antiques; their demands for justice are also half real half fake.

On a world half real half fake they gain a sense of unreal reality we might call transcendent!

Collected Poems by James Schuyler

The long poem “Hymn to Life” appears at the end of Schuyler’s 1974 book of the same name, which is now out of print — but contained within his Collected. Hymn to Life is a churning meditation on mortality and the essential beauty, horror, and meaninglessness of life. The poem is structured around the passage of spring in D.C. — a city whose blankness and stony facades the poem abhors — and in it Schuyler cycles between personifying nature and time, dipping into memories, and describing the life unfurling in the new season, its blue jays and daffodils and pear trees, not idealized but as they are, wavering in and out of existence as time tumbles forward, and also as real things framed by the modern world — sometimes diseased, existing among ugly monuments, glum weather, the sounds of chainsaws, noticed, forgotten about, wild, planted in corporate planters, with tourists milling about. Meanwhile, through it all, life, which is passing, picturesque, not picturesque, slips by and we remain unknown to ourselves, by turns grumpy and depressed, by turns astonished by its wonder.

Attune yourself to what is happening

Now, the little wet things, like washing up the lunch dishes. Bubbles

Rise, rinse and it is done. Let the dishes air dry, the way

You let your hair after a shampoo. All evaporates, water, time, the

Happy moment and—harder to believe—the unhappy. Time on a bus,

That passes, and the night with its burthen and gift of dreams. That

Other life we live and need, filled with joys and terrors, threaded

By dailiness: where the wished for sometimes happens, or, just

Before waking tremulous hands undo buttons.

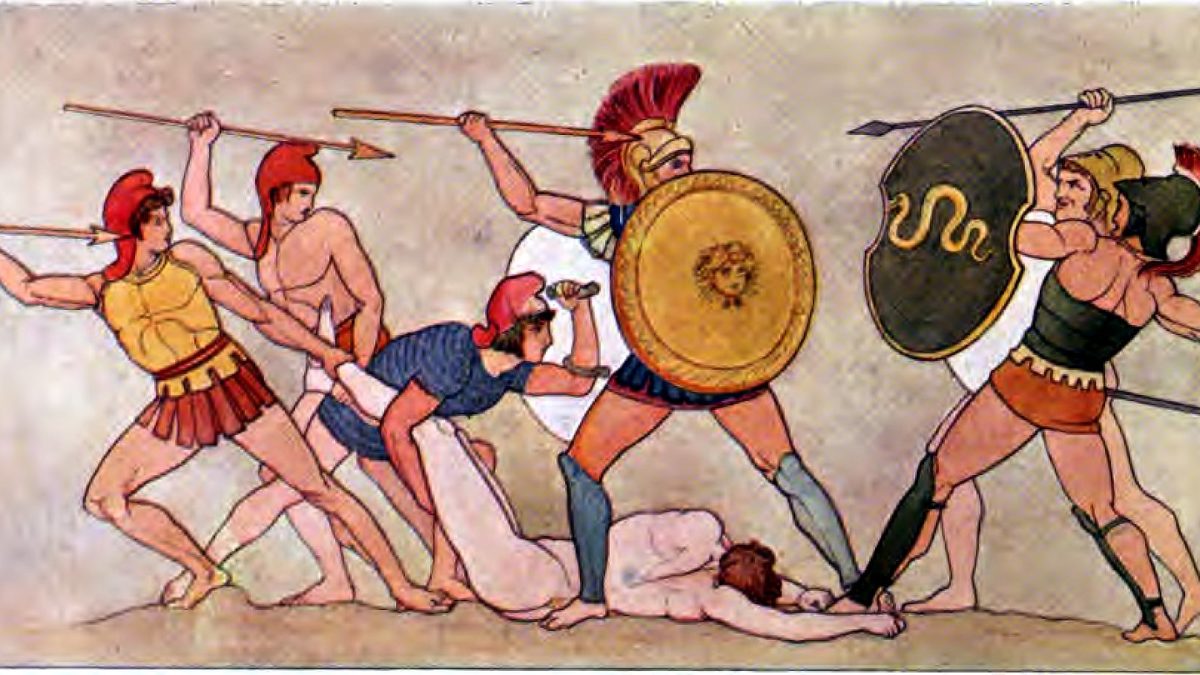

Memorial: A Version of Homer’s Iliad by Alice Oswald

Memorial is a fragmented, pared-down, interpretive translation of The Iliad that removes everything but the graphic deaths, elegiac laments, and similes. So what’s left is this timeless imprint of war, its waste and finality, interspersed with brief, impressionistic portraits of familiar kinds of men, their cowardice, arrogance, callousness, regret, terror, mixed with the eternal natural world and rhythms of life — an old woman’s spidery hands measuring wool, the weak petals of a poppy battered by rain, rocks battered by ocean water in an explosion of spray, a toddler raising its arms to be lifted by its mother. The portrait of a soldier who loved to sit on his front porch and make his friends laugh is an ancient portrait of a living face, the boys who died then, the boys who die today. The wastefulness of ancient war, of modern war; life as a sieve the world passes through, or the world as a sieve that life passes through.

Like when a mother is rushing

And a little girl clings to her clothes

Wants help wants arms

Won’t let her walk

Like staring up at that tower of adulthood

Wanting to be light again

Wanting this whole problem of living to be lifted

And carried on a hip

Pedro Pietri: Selected Poetry by Pedro Pietri

Pedro Pietri’s poems vibrate with indignation, revolving around those usually ignored — alcoholics, immigrants, the men who clean windshields at intersections, people living in government housing that’s overrun with cockroaches, people who play the lottery and have a collection of dreams. The most famous poem in this book, “Puerto Rican Obituary,” rotates around the refrain of a handful of names — Juan, Miguel, Milagros, Olga, Manuel — their hopes, exploitation, sacrifice, work, waste — the grayed-out half-life of people separated from their people, of people working now for a promised future that hovers forever just out of reach. Pietri’s poetry appeals to me in its stylistic irritability — the refusal to conform to prevailing conventions, veering into his own voice, manic all-caps, repetitions, patterns, deviations, dialect, surreal detours, a rhythm of his own.

All died

dreaming about america

waking them up in the middle of the night screaming: Mira Mira

your name is on the winning lottery ticket for one hundred thousand dollars

All died

hating the grocery stores

that sold them make-believe steak

and bullet-proof rice and beans

All died waiting dreaming and hating

Returning the Sword to the Stone by Mark Leidner

If Jack Handey wrote a book of poems, it might be a book like this one. Fond of aphorisms, surreal premises, outlandish but oddly familiar similes, and silly diction (on humility: “it feels awesome”), Leidner’s longish poems are absurd jokes taken so seriously they become unbearably sad and unbearably sweet. Beneath the jokes, the subjects are love, mortality, ego, and the mystifying beauty and pain of life. Reading these poems feels like playing NES with your friends for hours and hours, drinking 7-Up through Sour Punch straws, staying up so late that a feeling of wrongness seats itself in your chest — piercing pleasure, nostalgia, teetering between wells of joy and doom.

I hate it when I’m in geometry class

intent on disrupting the lesson

with inane and off-topic contributions

only to be moved to silence

by the beauty of the Pythagorean theorem

Air Ball by Molly Ledbetter

The long poems in this book are composed of lines of single sentences leisurely doled out with the pacing, structure, and confidence of a stand-up routine, in which set-ups are paid off in ways you didn’t anticipate. These are poems concerned with taste, status, posturing, heartbreak, small observations, grief, and the difference between art-world art and the actual experience of art, which is private, occurs in slivers, and is never as perfectly encapsulated as a prestigious gallery show written up in a brochure. Ledbetter bestows meaning on what would otherwise be detritus or ephemeral — your Uber ride history, children shouting “air ball!” from a nearby school, a handmade plate that reads “This too shall pass.” These poems make me feel as though I’ve spent an afternoon with a new friend, and have left with fresh observations uncoiling within me, which have unspooled dozens of new thoughts.

I never thought about where the train that cuts through the center of town was going.

Whatever I hear now in its whistle is like those bells in The Polar Express.

Like believing in believing in Santa, which I do.

Like bunk beds that squeak like an old wooden boat.

Like how good those nuts on the sidewalk smell at Christmas.

Like a mediocre cookie plate.

Back then, I could really have been someone.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.