There’s something transformational that happens when you unwrap a story across a series of poems. Without the real estate of an entire novel, the plot clarifies into its purest and most necessary form, unspooling without a single wasted breath. Metaphors focus and expand. Pacing spirals in on itself. The poet takes new risks on every page, building a text that doesn’t so much tell a story as sing it.

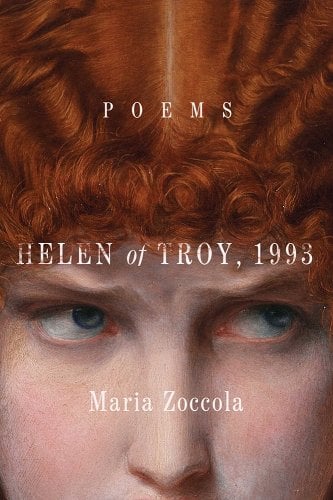

We humans have been using poetry as a vehicle for plot for thousands of years—it’s one of poetry’s original functions, after all. Think Gilgamesh. Think Beowulf and the Odyssey. Personally, I was thinking hard about the Iliad when working on my own debut poetry collection, Helen of Troy, 1993, which reimagines the Homeric Helen as a dissatisfied homemaker in small-town Tennessee in the early nineties. Helen comes of age, marries the wrong man, births a child she is not ready to parent, and begins an affair that throws her whole life into chaos—all this in poems with settings ranging from the produce section of a Piggy Wiggly to a Chuck E. Cheese birthday party to the opening night of Jurassic Park in theaters.

When I made my great leap into reading and writing poetry many years ago, it seemed only natural that the books I gravitated toward were the ones that told a story. The ones with a narrative arc, I mean. The ones with developed characters and weighted conflict. The collections building entire worlds inside their pages—and doing so while refusing to sacrifice the exacting attention to word and line and stanza that marks the very best of all poetic possibility.

Here are nine poetry collections that build their own narrative worlds.

I Know Your Kind by William Brewer

In the town of Oceana/Oxyana, West Virginia, opioid and heroin abuse has smothered everything in its path: lives, dreams, futures. Brewer uses a cast of characters to walk the reader through a community in crisis, addicts and their loved ones crying out inside a kind of living coffin nailed shut around them: “—Still fools? We? / Of course,” his characters roar into the winter night. Brewer is a West Virginia native, and his poems construct the breathing and dying Oxyana with a kind of tender authority that sweeps through halfway houses and hospitals and the dark rooms of the overdosed. His language is painterly, precise, frequently transcendent. An addict leaving a pain clinic proclaims, “though the door’s the same, / somehow the exit, like the worst wounds, is greater / than the entrance was. I throw it open for all to see / how daylight, so tall, has imagination. It has heart. It loves.” This book cradles Oxyana like a mother and like a house fire.

Trials and Tribulations of Dirty Shame, Oklahoma by Sy Hoahwah

When the little clay bowl Velroy Coathty uses to keep pocket change on his desk turns out to be the Holy Grail, Velroy is forced to make a run for it to get the Grail out of Indian Country ahead of the supernatural forces in pursuit. Other characters with their own paranormal problems join the journey along the way, and like modern-day Knights of the Round Table, Velroy and his friends band together to traverse the plains and fields of Oklahoma in a Comanche quest for the Holy Grail that may be just as doomed as those that came before it. Sy Hoahwah tumbles the reader down his cascading lines of action and imagery, building a narrative rooted in place and yet gently unmoored from any one specific moment. As Luther Tahpony, a boy both dead and undead, explains: “Inside that floating coffin is a fine line between me and time / It’s overwhelming … blinding, / like looking straight into eternity’s headlight eyes.”

Dear Outsiders by Jenny Sadre-Orafai

A pair of siblings living with their parents in a seaside tourist town must learn to fend for themselves when natural disaster strikes. Forced to leave the shore and all they’ve ever known, the siblings come to rest in the deep woods of a mountain, where danger still lurks all around them and the only sure thing is each other. Jenny Sadre-Orafai’s lovely, twisting book of prose poems treats the natural world as the ultimate hand of fate, both life-sustaining and life-erasing by unpredictable turns. “The ocean’s an animal head on a wall, and we can’t see the body. We think it must be inside the wall and that it walks out at night when we sleep. What’s a body really,” the siblings muse. Reading Sadre-Orafai’s prose poems is like peering into a room through a cracked door, discovering what’s inside only by what a single strip of light illuminates. We swim and hike and forage alongside our double-voiced narrator, living in their filtered memory as much as in the peril and beauty all around them.

A Season in Hell with Rimbaud by Dustin Pearson

French writer Arthur Rimbaud’s classic book-length poem A Season in Hell follows its narrator along a tortured journey through an underworld of unhappy love affairs and ruined dreams. Dustin Pearson’s narrator also descends, but in this collection, the narrator is searching through hell for his brother. “I tell myself / there’s not a world / without my brother in it. / I tell myself / I’d follow him anywhere / to keep the world / from ending,” the narrator says. The narrator and his brother enter hell together, but are almost immediately separated; to reunite, the narrator must embark on an allegorical odyssey of nightmares, burned by fire and frozen by ice, trekking ever onward through the landscape of hell toward a reunion of spirits beaten down and yet forged together by a shared past. Pearson’s imagery is inventive and unrelenting, and his poems locate themselves powerfully in the physical: “In Hell, all bodies are reduced. Flesh drops / from where it’s been burned, and where it lands, / separates.”

The J Girls: A Reality Show by Rochelle Hurt

Jocelyn, Jodie, Jennifer, Jacqui, and Joelle—coming of age in 1990s working-class Ohio—are teenage girls in the truest sense: each an individual battering ram of dreams, lust, prayer, joy, ennui, compassion, and nastiness. “We’re foul with ambition and clunky in pumps. Joelle fronts cool, but we cook up hot with no warning, man crazy,” Jocelyn says. Rochelle Hurt keeps the camera pointed at her five subjects as they gossip and play-act adulthood, harming each other and, deeply vulnerable in every sense, being harmed by the boys and men around them. Hurt’s phrasing and pacing are explosive, dense, experimental. Being caught up in one of her poems feels like opening a shaken can of Coke and watching it fountain across the room. Comparing herself to her ’81 Chevy Celebrity, Jodie says, “Both sixteen, we twin dim heads and cloudy rear-views, / collect red wounds on our underbellies where the world eats through. / Why should a body be this badly made for carrying?” In The J Girls, the reader watches teenage girlhood come apart and tape itself back together.

Ceive by B.K. Fischer

A modern-day postapocalyptic Flood myth, Ceive repositions Noah’s Ark as a container ship stacked with refugees aiming for the newly temperate Greenland. The book follows Val, whose daughter vanished in the disaster, as she reluctantly takes a place aboard the CC Figaro to look after the child navigator Crispin. Under the control of a single family (Nolan, Nadia, and their three sons), the Figaro locks into a new social order as it chugs onward toward its destination. Fischer’s pacing slings the reader through stanzas and prose poems that twin a deep understanding of loss with the requirement of moving forward, of living in the fractured present, the uncertain future. “You speak a few dead / languages now, the one / of profit and loss, shock / and awe, vote and veto,” Val muses, thinking as she often does of the world destroyed by the disaster that landed her aboard the Figaro: “You miss bathrooms but you don’t miss / the Dyson Airblade. You miss ice.” What Val misses most of all is her daughter. But aboard this new Ark, there is no way to go back.

South Flight by Jasmine Elizabeth Smith

After the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, lovers Jim Waters and Beatrice Vernadene Chapel must part: he to seek a future away from home, she to navigate the perils of a Jim Crow culture without him. Through letters they write back and forth to each other across their separation, Jim and Beatrice question and yearn and hope and dream, holding each other across the miles that keep them apart. “tell me what / happens when your hope for me / sprawls big as south, / yet this kind of living make me / smaller than a few chickweed seeds?” Jim asks Beatrice. Smith’s characters pulse with life, flush with the careful sensory detail work that threads throughout South Flight. “Honey. I ain’t saying break / don’t hurt, but it a simple fact this world will beat you / down, black eyes like jet, stricken you blue,” Beatrice imagines Ida Cox telling her at her dressing table. An Oklahoma native, Smith peers into a time in American history with painful parallels to our current cultural moment, building both blues and love story along the way.

Troy, Unincorporated by Francesca Abbate

I stumbled upon this collection very recently, and I’m so glad I did—Troy, Unincorporated feels like it could be cousins with my own debut collection. Francesca Abbate brings Chaucer’s version of the tale of Troilus and Criseyde to modern rural Wisconsin in a series of dreamlike poems darting through language and consciousness. Troilus and Criseyde fall in love among the lakes and rains and birds of their small-town home, but any reader familiar with these classic characters knows that this young love can’t last. When Criseyde leaves town and falls in love with another, Troilus is utterly bereft, and there is nothing his friend Pandarus can do to save him from himself. “I am half-invincible, / half-destructible, half-mad: am, in fact, a divine half / and a half not,” the character Psyche sings in one poem; this book, too, exists in married halves. Abbate holds Greek myth in one hand and Chaucerian tradition in the other, weaving them together into something entirely fresh and original: “narrowing road, clearing, / the sun like the secret shining in the dark halves of all things.”

Pretend the Ball Is Named Jim Crow: The Story of Josh Gibson by Dorian Hairston

“Joshua ‘Josh’ Gibson is the greatest catcher to ever play the game of baseball,” Dorian Hairston writes in his author’s note. In a collection of persona poems that dive between complex interiority and the base-stealing drama of the diamond, Hairston brings Negro League baseball to life through Gibson and his contemporaries, holding the long shadow of American segregation and racism in constant focus. “uncle sam knocked / on my door drafting / some black shields / for his white sons / and I answered in my draws / slung my bat up over / my shoulder and point him / in the opposite direction,” Gibson reflects in one poem. Hairston gives narrative space to Gibson, his children, outfielder Hooks Tinker, journalist Chester Washington, and others, all these voices shaping the landscape of our national pastime in the 1930s and 40s. Hairston is a baseball player himself, and his love for and deep knowledge of the game shine out in his work: “I never seen something so smooth. / how Josh didn’t rock or sway back / before the pitch, he just waited there / in the box like a snake to strike.”

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.