My mother was movie obsessed. It was a hold-over from growing up in a tiny town in rural Oklahoma in the ’40s, when many families went nightly to the cinema to get their news and stay for a film. It was cheap, and a place to escape dustbowl poverty into silver screen glamour. The gilded, grand route 66 movie theatre—velvet curtains, opera boxes, an orchestra pit—that my mother went to when she was a kid (to see Citizen Kane, The Third Man, Casablanca, Gilda) was the same one where she took me when I was a kid, forty years later (to see Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T., Romancing the Stone, Crocodile Dundee). By the ’80s it was derelict and moldy, the threadbare velvet seats mostly broken, the paisley carpet indelibly stained, and the aisles sticky with decades of spilled Pepsi.

Article continues after advertisement

My mother didn’t have a lot of friends who shared her passion (she didn’t have a lot of friends at all) so when she had kids—somewhat late in life—my brother and I became her acolytes in this church of the screen. While other parents took their kids to the lake or the park or the library, we went to mall multiplexes and video stores.

Most readers won’t notice these undercurrents, unless they had an upbringing like mine, but they remain in the work.

She stayed up all night watching replays of Friendly Persuasion or A Letter to Three Wives whenever they aired, no matter how late at night. I can remember being dragged from bed to watch 2 AM features of Brigadoon, Funny Girl, and Roman Holiday and then being kept out of school the following day to allow me to recover. In 7th grade, she called in for my absence once so I could stay home and watch Sex, Lies, and Video Tape before it had to be returned to the rental store at 5 pm, because she thought it was a masterpiece.

My film education—star biographies, Hollywood gossip, tabloids, minutia of trivia—was not only comprehensive, but de rigueur. There was a sense that being unaware of such things—that Olivia De Havilland and Joan Fontain were sisters (who hated each other) or that Rita Hayworth had been married to Orson Welles (but left him because it was hard to be married to a genius), or that Humphrey Bogart wore wedgies and seduced Lauren Bacall when she was 17—was to be ignorant in general, and backwards in the extreme.

My mother’s subjectivities also became rote facts to be memorized: in 1945 Mildred Pierce should have won the Oscar but didn’t, in 1951 Streetcar should have won but didn’t, in 1976 Network should have won but didn’t, etc. She didn’t pay much attention to what kids should or shouldn’t watch—at age seven, I woke up in the back seat of our station wagon at the drive-in to a suicide scene from An Officer and A Gentleman, having been transported from bed in a sleeping bag sometime in the night. In my memoir, Rerun Era, I wrote about her taking me to see The Elephant Man when I was five—trauma ensued—but she also let me rent Taxi Driver at age six or seven—I strongly identified with Jodie Foster as the child prostitute, because I knew I had been named after the actress (and carried her nickname well into my teens).

The list of films with adult content was endless, and I can remember many instances of my mother negotiating with the teens at the ticket counter to allow me into R-rated films, in part because she thought these films taught would teach me something essential about life or love or politics, but also because I was her only companion, and she never, in her entire life, went into a movie theatre alone.

If there was an ungettable film, and she couldn’t show it to me, she would just describe it, retelling it dramatically, practically in real time, from her memory—I remember her starting the story of Rosemary’s Baby once when we were out at the Safe-way, and continuing it on the drive back to the house, keeping me sitting in the car under the carport for half an hour until she got to Ruth Gordon’s famous line, “He has his father’s eyes!” while the rainbow sherbert melted in the backseat. When she did these story-telling sessions, she spared no detail, and interwove the making-of facts, and behind the scenes drama in with the dramatic recounting of scenes, plot, dialog. Even though her memory for film details was astonishing, she often got things wrong, or revised them, or mixed up one film with another—often I think, willfully. The legends of these films in her telling often outstripped the film itself when I finally got a chance to watch it.

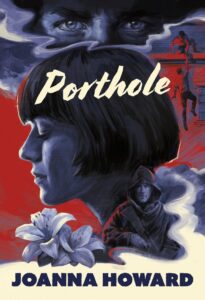

All of my books so far have had some film that anchors the concept, or which runs as an undercurrent, invisibly below the writing. Often films I remember most vividly not from watching, but from my mother’s descriptions and recounting—like Now Voyager, a Bette Davis film that is one of the touchstones for my new novel Porthole which is about a film maker recovering from breakdown after a death on the set of one of her films. Character names, many of the locations, even some of the costumes appear. I can remember my mother describing the cruise ship in Now Voyager that Bette Davis has taken after being released from a mental asylum, under the care of Claude Rains as an eccentric doctor.

Writing about a filmmaker for Porthole was a kind of culmination of all these film memories and factoids that my mother infused into me.

My mother always paused dramatically when she got to the big romantic moment when Paul Henreid lights two cigarettes and then passes one to Bette Davis. Where does one even put something like this scene in the 21st century if it is still hovering in your head? And how do you reclaim it for you own era, for your own ideas about love, or madness, or even smoking? Readers don’t need to see the references—in fact, they are meant to be subterranean. Most readers won’t notice these undercurrents, unless they had an upbringing like mine, but they remain in the work, these little traces of the movie-stories, from my montage brain, like secret messages from my earlier self to my current self: a circling of characters, actors, anecdotes that keep me asking about those floods of film narrative that formed my opinions, attitudes, aesthetic—for better or worse, which are often in need of some critical thinking, even as they hover, dramatically in a nostalgia of my earliest love of story-telling.

And while I found my mother’s spoilers maddening when I was young, her habit of story-telling movies is one that I have now. A desire to retell a film I’ve seen according to my own memory, and make it my own, the way we wake-up in the morning and tell our dreams to someone as a method of understanding or claiming. And it is structurally similar to the way I write fiction—remembering plots from things I’ve read or seen, mis-remembering them, often willfully to reclaim them for my own values or expose their hidden biases, their blindspots. Sometimes it’s recasting them, rescripting, or splicing a few different things together in my mind to make a unique story out of two banal ones. It’s a claiming, but also a sorting-out of images, the natural montage of the memory.

I had a difficult relationship with my mother—most of my memories of her are filled with conflict—but this one piece she gave me, this love of film, is something I can’t deny, even though at times, I’d like to. I can’t say if, as a child, I loved all the same movies she did, because there was only her opinion, not much room for dissent. In later years, I tried to form my own taste, in college going for foreign arthouse or indie, while she stuck with Hollywood blockbusters—things that seemed sentimental and schlocky to my aggressively forming intellectual biases. But often I secretly watched those same films and loved them anyway.

Writing about a filmmaker for Porthole was a kind of culmination of all these film memories and factoids that my mother infused into me, and the stories she told of films and about films. Even though my main character is much more French noir than Hollywood silver-screen in her formation, its all in there. Porthole gave me a place to reconcile the clash of influences, the incredibly mixed feelings I have around my film erudition, and writing it gave me the chance to just let the films I loved and the films my mother loved sit together in their juxtaposition, in their discomfort.

__________________________________

Porthole by Joanna Howard is available from McSweeney’s Publishing.