Discovering Souvankham Thammavongsa’s stories had been accidental, or what I would call serendipity. To me, her stories depict a necessary form of hope. In fall of 2021, I had just returned to the USA after spending six months post-pandemic at home in India, when my homesick heart returned to Thammavongsa’s story collection How to Pronounce Knife. A friend had recently gifted me a fountain pen that became the best pen I’ve ever owned, and partly because I wanted to keep writing with that pen, I opened my writer’s journal and copied the story “The Gas Station” from beginning to end by hand. It felt important—perhaps even urgent—that I spend such careful time with the story’s rhythms and its 36-year-old accountant protagonist, Mary. It’s the first and last story that I’ve ever had the urge to engage with in this way.

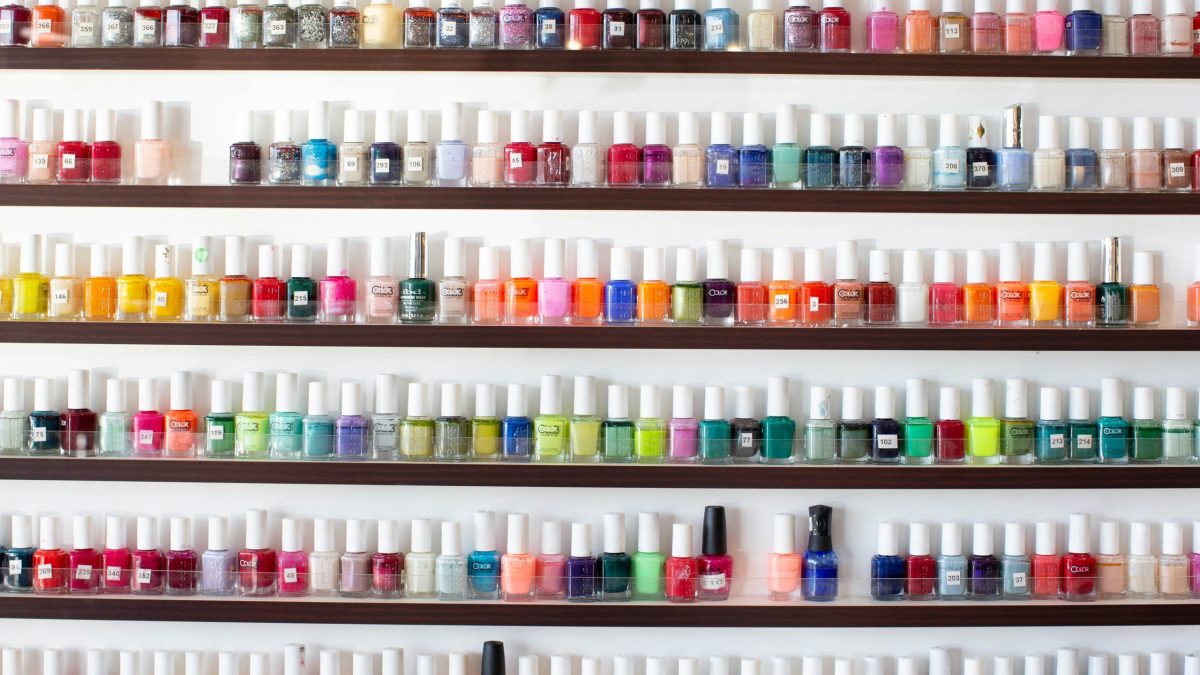

Thammavongsa’s fiction astounds me—I have reread her stories multiple times, taught “How to Pronounce Knife” and “Randy Travis” to my undergrad writing students, and learnt the craft of writing from her work. Her debut novel, Pick a Color, is another example of all the things that make Thammavongsa’s craft shine: its airtight form, soulful characterization, and the evocative portrayal of the mundane. Pick a Color follows a nail salon owner, Ning, through the course of a day. The novel opens with the opening of the nail salon and closes with the closing of the nail salon. It could’ve been any other day in the narrator’s life, and in many ways it is, but having gone through the experience of living it with Ning, a reader is changed. The novel quietly burns with the power of human love and friendship.

Souvankham Thammavongsa and I corresponded about her forthcoming novel via email. We discussed the art of absence, making what is real fiction, and keeping the reader wanting for more.

Apoorva Bradshaw-Mittal: A constant theme running through the book is a form of witnessing. Ning and her employees are looking in on their customers, Ning is looking in on her employees, and finally the reader is looking in on Ning. Why do you think witnessing is important for this book?

Souvankham Thammavongsa: You’re right. The novel is not built on plot. It is built on voice and that alone has to be made to carry things.

Writing about a nail salon worker is usually done from the outside, through someone else’s gaze. Seen as quiet and sad, pitiful, shameful, disgusting, and only from a glance. I don’t do that here.

I make the English speaker feel foreign in their own language.

The novel asks you to pretend the English language right in front of you is not there. We are told that they are speaking in their “own language” but the joke is that it is actually the English language right in front of us. I am not translating a language. I am writing in the English language, but I make it feel translated. When we do hear from people who are speaking English they are only heard from twice saying “yoo-hoo” and “whoa, whoa” which are just weird sounds. I make the English speaker feel foreign in their own language.

There’s a difference between point of view and perspective. Anyone can just choose a point of view, but a writer’s real talent and magic happens inside what they can do with perspective. We can feel how loud her life is, what she cares about, her pride and her power. Wherever we come from, whatever it is we do in our own lives, we are made to be a nail salon worker—we are not just a reader reading about the nail salon.

ABM: It’s common in your oeuvre to keep your characters unnamed. You have talked in your past interviews about how namelessness creates a sense of universality. But in Pick a Color, not naming serves a different purpose. Could you talk a little bit about the purpose of namelessness as it applies to the lives of the characters in the book?

ST: The girls are nameless to the clients, but not to themselves or each other—and in this world they matter only to themselves and each other. In fact, it is the clients who feel nameless actually. In the nail salon world, you do not want to be named. Who wants to be “Asshole” or “Miss All Caps” or “Finger Toes”? A name is powerful. It can place you and also undo who you think you are.

ABM: As you said, the reader gets to be a nail salon worker for the course of the book. We’re privy to Ning’s deepest thoughts. Through the book, you’ve created such a careful balance between a slow unraveling of Ning’s history and preserving some of the mysteries, such as Ning’s missing finger. How did you choose which mysteries to reveal and which ones to not? What about the questions that remain unanswered?

ST: The novel takes place in a single day. I worked not to betray the form.

A name is powerful. It can place you and also undo who you think you are.

I am a writer of absence. I write what is there, but I spend a lot of time making what isn’t there as well. I love that readers are left with so much. That the characters and lives live with them long after they get to the last page and close the book. A life has been made so real to them. To earn a reader’s want like that and to have them still want even when the book is done feels like an achievement to me.

ABM: The finger feels especially important in its absence. It’s also one of the biggest unsolved mysteries. Is it the irony of a missing finger in the profession where fingers are important? Or is there something more?

ST: It is not just any finger. It is the ring finger. To tell what happened to that missing finger is a great question for basic reasons like information, practicality, plotting, closure. But that question does not serve art. To tell would diminish how I have made it missing in the first place.

ABM: I love what you said about being a writer of absence and creating art through absence. What you describe is ars poetica to me. And well, you are a poet. How does being a poet play into your fiction?

ST: I don’t lean on my poetry. It exists as a work in itself, and I am confident that it does. I don’t drag my poetry into fiction and insist it be called fiction. I am confident in my prose. I don’t romanticize not being understood. I think when you enter the house of fiction, you leave your shoes at the door.

ABM: I want to talk a bit about the characters and relationships in the novel. Ning is a strong woman, and as you said, powerful. Early on in the novel, Ning says that she chooses to be alone and that she is a family of one. But that’s perhaps not the entire truth. She has many relationships she holds important, and a dynamic that’s present in all these relationships is one of a teacher and a student. Ning has been a student of her boxing coach and then of Rachel, the owner of the nail salon Ning worked at before starting her own. Now she is a teacher to the girls that work for her. Did you see these mentoring relationships fulfilling some need that other conventional relationships cannot for Ning?

ST: I think Ning is alone but she does know love. She is completely devoted. To her work, to the girls, the shop, her clients, being the best at what they do there. And they all carry her the way love can.

ABM: Who do you see Rachel as? Who is she to Ning? And who is she to the story?

I don’t romanticize not being understood.

ST: This is a great question. The novel is about female friendship, and there’s a lot of space to read into that. I don’t think Ning knows exactly who she is and who Rachel is to her, but this is a day that when she looks back she might see a beginning or maybe an ending of some kind. And let us just leave it at that.

ABM: Rachel and her brother, Ray, have been a part of another world—the story “Mani Pedi” from your short story collection. Ning and Ray’s life paths have been similar. In fact, “pick a color” is something that Ray used to say to his customers when he first started at Rachel’s salon, because he couldn’t remember all the colors. So we can see that Ray has influenced Ning in some ways. But in the book he is only ever a mentioned character, never appearing on-stage. Could you talk a little bit about how Ning started as a character for you, and why Rachel makes an appearance in the novel, but not Ray?

ST: The novel is built out of a short story, but I didn’t want to expand that. That would be too easy. I wanted that short story to stand alone and remain self-contained. I felt Rachel was too angry as a voice and Raymond was not interesting to me as a voice.

My dad always told me he never had to worry about me. That I would always find my way. For a parent to say that to you, I think, is an incredible compliment. I was really down and out, preparing taxes by myself at a kiosk in a Wal-Mart when my dad said this to me. Whatever life was going to give me, I would find a way to love it and to do my work well with incredible pride. I wanted to read about a person like that.

I didn’t have a name for the narrator in the novel and thought of leaving her nameless, but in the middle of writing the novel my brother died. He called me Ning. I thought of how I might never hear that name again, so I named her Ning. [I] wanted someone to say her name out loud over and over again so that I might hear my brother’s voice come alive.

ABM: Thank you for sharing that with me. Now the part where Ning’s name is gifted to readers makes even more sense and seems even more special. Does hiding kernels of truth in the fictional help you make your characters real?

ST: I don’t think there is such a big divide between what is real and what is fiction. Even when something is real, we still do the hard work of making it up.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.