“We were all considered slightly cracked, if not outright fanatics, that first year.”

—Larry Lader, Abortion II

“Abortion is the dread secret of our society.” So began journalist Larry Lader’s controversial book, Abortion, published in 1966 after years of rejection from publishers. If you had told Lader or the mere handful of activists then dedicated to legalizing abortion that a Supreme Court case would overturn anti-abortion laws across the US seven years later—in a January 1973 case named Roe v. Wade—they probably would have laughed. In fact, in the early 1960s when Lader began researching, it was harder to get an abortion in the US than it had been in the early decades of the twentieth century. In 1966, American doctors—who were overwhelmingly white men—tightly controlled women’s reproductive options. And women of color, primarily Black and Latina women, had even fewer choices if they found themselves accidentally pregnant. Nearly 80 percent of all illegal abortion fatalities were women of color—primarily Black and Puerto Rican. And, worst of all, as Lader documented, deaths from illegal abortions had doubled in the preceding decade.

Before Lader’s book, no one, it seemed, wanted to talk about abortion publicly. But something changed with the 1966 Abortion. For starters, Reader’s Digest—one of the bestselling magazines in the US at the time, with a circulation of millions—excerpted eight pages. This thrust Lader into the limelight, turning him from a journalist into an abortion activist almost overnight. He began receiving hundreds of letters and phone calls to his home from people asking for contacts for abortion providers who would perform the procedure safely. Lader’s wife, Joan Summers Lader, remembers receiving the calls at all hours and worrying that their phone might be tapped. She advised women to write to their home address with their request, because if necessary, letters could be burned. They worked tirelessly to make sure that no woman was turned away and received a safe and affordable abortion, if possible.

Because of Abortion, Lader found himself at the center of a burgeoning radical abortion rights movement. Activists, lawyers, religious leaders, and health practitioners from across the country who supported the repeal of abortion laws reached out to him, applauding his book and asking what they could do next to advance their cause. In 1969, with Dr. Lonny Myers and Reverend Canon Don Shaw in Chicago, Lader organized the first national conference dedicated to overturning abortion laws. He insisted that the conference’s efforts should result in a national organization that could continue centralizing the efforts of local repeal groups. On the last day, he chaired a meeting with hundreds of people, trying to bridge differences and prevent shouting matches, mediating between those who wanted to forge ahead and those who were more cautious. At the end, NARAL was founded. In those early days its name stood for the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws, and its ultimate goal was precisely that: to repeal all laws restricting abortion.

Six decades ago, Lader’s book launched a movement. In the days before the internet connected people, Abortion served as a link joining activists, doctors, lawyers, clergy people, and others impacted by restrictive abortion laws, who felt deeply that those needed to change. Doctors saw firsthand how anti-abortion laws killed, maimed, and emotionally destroyed women who couldn’t have safe and legal abortions; progressive clergy people understood the trauma inflicted by these laws and how they alienated people from religion; and lawyers saw an opportunity to extend new privacy protections afforded by the 1965 Supreme Court case Griswold v. Ferguson, which finally legalized birth control for married couples. And of course, women, their partners, and their families understood firsthand how anti-abortion laws curtailed their lives and limited their freedom.

Still, bringing people together to start a national movement on a controversial subject that rarely received sympathetic attention from the media or politicians was challenging. Abortion, however, proclaimed loudly that all abortion laws should be repealed, that there was no shame in seeking an abortion, and that without legal abortion women would never be free. It was the needed spark to bring together a movement, and Lader embraced his role as its convener.

For nearly a century, abortion had been outlawed in every American state. Some of the earliest anti-abortion laws were passed as antipoison measures to protect women who were sold toxic chemicals claimed to be abortifacients. However, by the 1860s, it was clear that most anti-abortion laws intended to control women’s reproduction to keep them in the domestic sphere. Nineteenth-century anti-abortion rhetoric framed abortion as unnatural or as interfering with (white) women’s moral duty to reproduce for the state. Despite these restrictions, however, abortion did not go away.

When, in 1962, Lader decided to write about abortion’s history and present-day consequences, he received little support at first. He was a seasoned magazine writer with two published books. Even so, he was surprised that—even with all his connections, even as a white man—it was impossibly difficult to find an editor willing to publish a pro-legal abortion article in a mainstream magazine. In letter after letter, he pitched a long-form article that would present his research on the impact of anti-abortion laws to show the harm they caused. No editor was willing. One wrote back that he had become “a little squeamish on the subject,” and he recommended Lader “find an editor with more guts.”

Rather than give up on the project, Lader decided to dive deeper, and he wrote a book proposal. Abortion would be the first book to explore the history of the procedure in the US and make a case for repealing all abortion laws. It was a radical decision, and Lader knew it would open him up for attack. He also worried that it might kill his career as a magazine writer and ensure he was never again offered an assignment. Still, he decided to forge ahead. More than 12 publishers rejected the proposal before he found an editor willing to give him a book contract with the Bobbs-Merrill Company.

In 1964—when Lader was knee-deep in abortion research—there were an estimated 1.1 million abortions a year in the US. Only 8,000 of those were legal “therapeutic” abortions, performed in hospitals that were approved by a panel of doctors. In 1955, therapeutic abortions for psychiatric reasons made up 50 percent of all hospital abortions; by 1965, only 19 percent of abortions were given for psychiatric reasons. That means that almost all women sought the procedure illegally. Of those 8,000 legal abortions in hospitals, virtually none was given to Black and Puerto Rican women.

Before the internet connected people, “Abortion” served as a link joining activists, doctors, lawyers, clergy people, and others impacted by restrictive abortion laws, who felt deeply that those needed to change.

As Lader wrote, there was one abortion law for the rich and one for the poor. In other words, only women with financial means could buy their way to a hospital abortion given under safe and legal conditions. In Abortion, he argued that legal abortions should be available outside the hospital setting—in freestanding abortion clinics—because hospitals too often treated patients as “pawns” and cared more about preserving their reputations than about preserving the health of their patients. He also saw how some hospitals still sterilized patients against their will as the price for agreeing to offer an abortion.

Abortion not only presented a history of abortion in the US but also functioned as a handbook for people looking to connect with an abortion provider. Lader was careful not to publish names, but he included a chart of how many skilled abortion providers he could locate in 30 states, including Washington, DC. He also explained the practicalities of traveling to Puerto Rico, Mexico, or Japan for an abortion.

In another chapter, titled “The Underworld of Abortion,” he explored what happens when abortion is illegal and unregulated. He noted that the victims of illegal abortions are people who can’t afford to travel and so resort to getting abortions from unqualified people—sometimes doctors who had lost their license for alcoholism or other substance abuse issues. Because these abortions were underground, safety standards weren’t always followed; if unsterilized equipment was used, it increased the chance of infection. Some desperate women resorted to self-induced abortions, and although determining the numbers was difficult, one Kinsey study of Black women and of white and Black incarcerated women estimated that 30 percent of abortions were self-induced. These abortions were especially dangerous, often leading to lethal infections or infertility.

For all these reasons, he argued for the complete repeal of all abortion laws across the US. He believed abortion should be no more regulated than any other routine medical procedure.

When Lader became interested in abortion politics, there was a tepid abortion reform movement in New York City, led in part by the gynecologist/obstetrician Alan Guttmacher. Guttmacher participated in the first conference organized about abortion by Planned Parenthood’s medical director, Mary Calderone, in 1955. However, following Planned Parenthood’s stance on abortion in the 1950s, the conference focused on abortion to highlight the need for better contraception, and most of the participants supported anti-abortion laws. When proceedings from the conference were published in 1958, only Guttmacher’s contribution emphasized the need to liberalize those laws.

However, even Guttmacher only supported abortions performed in hospitals, approved by a board of doctors, and limited to cases that merited it because of the woman’s mental or physical health. As head of obstetrics and gynecology at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, he created a panel of doctors to approve abortions, and the number of approved abortions grew modestly. In 1959, Guttmacher—with the help of his twin brother, Manfred—joined with the influential American Law Institute (ALI) to draft the first abortion reform law, which would allow for abortion in cases where continuing the pregnancy would affect the woman’s physical and mental health or if the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest. The law also mandated that two doctors had to approve the abortion.

The law lowered the bar and created clearer guidelines for obtaining an abortion. Still, it maintained that abortions should only be performed in hospitals, and women had to submit their request for an abortion to a panel of doctors for approval.

In his unpublished memoirs, Lader recounts considering what position to take on abortion. He knew he stood against the laws that imposed severe restrictions, making it virtually impossible for most American women to obtain a legal abortion. But as he set out to write on the topic, he consulted with his wife about how far to go in his argument for legalization. Was setting a limit after 20 weeks of pregnancy reasonable? Should abortions only be performed in hospitals? What about limiting the reasons under which an abortion is permissible? Should it be allowed under all circumstances or for no stated reason at all? Lader knew that arguing for a complete repeal of all abortion laws was radical, given the barely existent conversation about changing the laws at the time. After talking with his wife and remembering how he helped his ex-girlfriend’s friend obtain an illegal abortion, driving her to Pennsylvania, he decided that the terms of legal abortion should never be circumscribed by law.

Lader subtitled the last chapter of Abortion “The Final Freedom” because he believed that “The ultimate freedom remains the right of every woman to legalized abortion.” He cites Margaret Sanger, the subject of his first book, who argued for birth control under similar terms: a woman cannot call herself free until she can control her own body. Sanger never argued for legal abortion because she naively believed that with accessible and effective birth control the need for it would be obviated. Lader understood that the natural extension of Sanger’s argument is not only legal but also affordable abortion with no strings attached. He presciently recognized—decades before its invention—that if an abortion pill could be invented, it would radically transform abortion access. Lader was not a religious man, but he sought the help of clergy—from the Reverend Howard Moody to the Rabbi Israel Margolies—who supported the repeal of all abortion laws. Recognizing the power of religious leaders to sway public opinion, he ended his book with the rabbi’s words: “Let us help build a world in which no human being enters life unwanted and unloved.”

This essay refers to people seeking abortions in the period before Roe v. Wade as women, which was the language used by people at the time. However, I’d like to recognize that not all people who need abortions today identify as women. ![]()

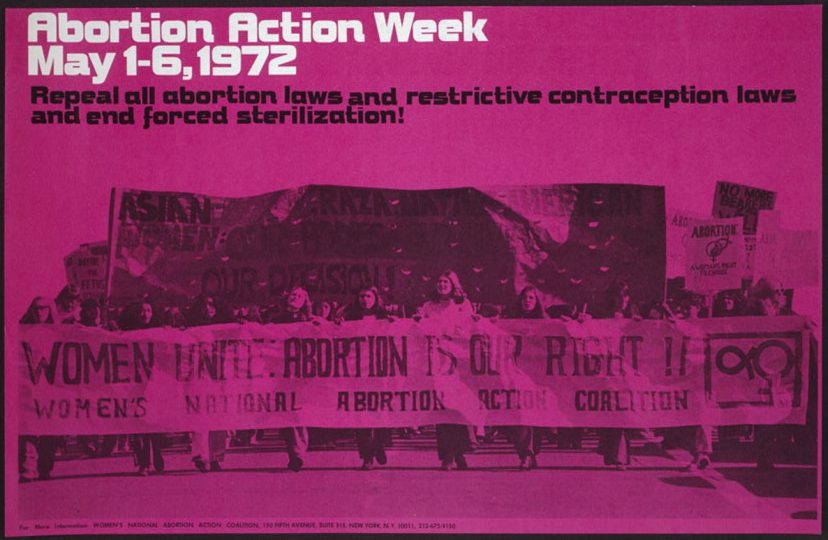

Featured image: Women’s National Abortion Action Coalition poster for Abortion Action Week, May 1-6, 1972. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.