I drafted and revised this article in longhand, something I haven’t done since the mid-1990s, unless you count the occasional brainstorming I do in my journal. I made this choice because I’ve been worrying about how technology might be encroaching on my writing skills. I wanted to know what it would be like to return to the old ways.

I recognize that the overall loss of skills to technology is nothing new. After all, most of us don’t know how to hitch a horse to a wagon or spin yarn—although I’m interested in learning the latter. The world changes, and that’s okay. But in the digital age, innovation happens at lightning speed, with the results often integrated into our lives overnight—literally—and without our consent. That’s what happened when I woke up a week ago to find Microsoft Copilot, an AI writing assistant, installed on my computer—not as a separate app but as an integrated aspect of Microsoft Word. Its little grey icon hovered next to my cursor, prompting me to let it do my job for me. I spent an hour trying to get rid of it until I finally settled for turning it off.

I feel more and more that technology doesn’t liberate me as much as it diminishes me.

I value many technological innovations, such as the technology that enabled my laparoscopic surgery a few years ago. I think my Vita-mix is pretty darn nifty. And I’ve never doubted that the washing machine set us all free. But in recent years, I feel more and more that technology doesn’t liberate me as much as it diminishes me. Technological innovation has always had this darker side, slowly eating away at the things humans know how to do, or in the case of automation, the things humans get paid to do. But lately, the stakes feel higher. Where I used to feel new technologies robbed me of things I enjoyed doing, like driving a stick-shift car or operating my all-manual thirty-five millimeter camera, I now feel them getting into my head, interfering with the way I think, with my ability to process information. I worry: Am I forgetting how to add? How to spell? How to navigate the maze of streets in the metro area where I’ve lived for over forty years? Am I forgetting how to listen to and comprehend a film without subtitles, or how to read a novel?

That’s a lot of forgetting.

I have tried to resist many of these encroachments, tried to push back to preserve the skills that used to be rote, but I find it increasingly difficult. I feel my intellectual abilities slipping, despite myself, and I know: I am diminished. Now, technology is coming for my most valued skill, the one that has defined me since I first learned my letters: writing.

Of course, I am not alone in my fears about AI and how it might affect my profession as a writer and editor. We all have concerns about property infringement, the loss of jobs, the banality of ideas only formulated by the clunky cobbling together of what’s already been written and fed into the maw of the large language model (LLM). But I have an additional concern. For me, and for many like me, writing is not just a way of communicating, it’s a way of thinking. I rarely begin an essay with the entire thing planned out. Who does? Even if I have an outline, I will not yet have made all the connections that will come to be, let alone have planned out such things as metaphor, imagery, or other figures of speech that emerge in more creative pieces. Something about the state of suspension the brain enters while holding ideas in the air and doing the busywork of typing letters, spelling words, inserting punctuation into grammatically correct sentences, creates space where connections happen and ideas spring. It resembles the way a thing as simple as a person’s name will come to you when you let yourself think about something else. The physical act of writing serves as the distraction that lets the ideas flow. But also, and perhaps more importantly, writing forces the writer to think very slowly, only allowing the brain to move through an idea at the speed at which each individual word can be written. Perhaps that elongation of thinking gives the brain the time it needs to have new realizations. So much discovery happens as a piece of writing evolves that, like many writers, I often set out to write with the purpose of finding answers and prompting evolutions. In this way, writing itself functions as a generative act, a process of discovery and learning that far exceeds the simple recording and communicating of already formed ideas.

The physical act of writing serves as the distraction that lets the ideas flow.

Drafting this essay in longhand led me to think beyond how AI might affect this generative process to consider the other technological changes that have affected my writing over the course of my lifetime. Have those changes also impinged on writing’s process of discovery? I grew up with the unfolding of the digital age. In fact, I’m old enough to have begun writing my school papers with a pencil, reserving the pen for my final drafts. I remember the day when I decided to forgo the graphite and draft in ink. I had to adjust to the permanence of ink on the page when I’d yet to finalize—or sometimes even formulate—my thoughts. The typewriter came into the picture when my sixth-grade teacher required our class to turn in a typed final draft of our research papers. From then on, I typed all of my final drafts for school, progressing from a manual typewriter to an electronic one during high school and experimenting with various inadequate forms of whiteout in the process. I didn’t begin using a computerized word processor until college in the 1980s. And it was bliss! Anyone my age or older knows what a gift the invention of word processing felt like. The ability to add, delete, or rearrange text without having to retype entire pages just to correct one word was pure freedom. The composition on the page became so much more fluid, and the process of creating it so much faster.

But even then, I only used the computer as a glorified typewriter as I continued to compose all of my drafts by hand. It actually took years before it occurred to me to compose on the computer. During grad school, I wrote in longhand, typed up the draft, printed it out, edited it in hard copy, then typed the edits into my digital version, printed again, and repeated. However, when I found myself printing the same 25-page term paper multiple times to edit it, the wasted paper prompted me to consider editing straight on the computer. This process evolved until I finally decided to try composing there as well. Making the leap felt overwhelming because I did not yet know how to think about anything other than typing while typing. The integration of keyboarding into the already merged tasks of formulating ideas and composing grammatically correct sentences gave me the feeling of trying to fly without the proper means.

Of course, I adjusted. And soon I was flying. My fingers raced over the keyboard, enabling me to move through my ideas with a rapidity handwriting could never afford. Composing on the computer happens delightfully fast, but I wonder: if writing is a process of discovery and learning, then what discoveries did I lose by speeding up the process? What connections haven’t I made? Is there a level of richness or complexity I haven’t achieved because I’ve spent less time engaged in that magic writerly state of mind and therefore, less time exposed to the possibility of revelation? I can’t escape the thought that if slowness is key to writing, and writing is a way of thinking, perhaps each tech-driven acceleration of the process has chipped away at my depth of thought.

If writing is a process of discovery and learning, then what discoveries did I lose by speeding up the process?

Ironically, I found the return to hand writing an essay painfully slow at first. Although I eventually rediscovered my old routines, I initially had moments where I couldn’t wait to get to my computer so I could just get it down already—see the clean and neat print on the screen instead of my messy scratched up pages. I also noted that it took me forever to get started. I mulled over my ideas for weeks before putting pen to paper, in part because I felt a pressure to have all my thoughts together first. Before completing my first draft, I saw this delay as an impediment—thinking the prospect of writing by hand had held me up, slowed me down. Now, I see that prolonged period of contemplation as a benefit, providing another means of slowing down that gives the element of time its due, allowing it to generate and enrich ideas. This is why I always try to sleep on a draft before turning it in to a client, why taking a break from writing can help writers problem solve and iron out difficulties in a piece.

Writing is hard, so I see why some might be tempted to let a machine do the initial composing. The blank page represents the most difficult phase of writing because this is when the writer must engage with their topic most fully. In the absence of time or energy, AI might sound like a great solution—just as past innovations felt like godsends. But AI brings changes far more dramatic than those of the typewriter. If I let an LLM compose my first draft, only to edit and shape it and supposedly make it my own afterward—as I’ve heard some writers suggest—then I would have skipped over that initial composition process, that period of intense intellectual engagement through which we enrich our ideas. I would sacrifice the element of discovery, learning, and creation in favor of the LLM’s regurgitation. If the future offers a world filled with AI-produced prose, who knows how much we will collectively lose to writing created without all those unique incidents of epiphany and realization.

The idea that technology may have reduced the generation of ideas by speeding up my writing process came to me while working on this essay. I didn’t begin with that thought. I simply began with a question about how technological change had affected my writing. Answers came through my writing process. Realizing this, I decided to put the same question to ChatGPT. I used a few prompts: How has word processing changed how we write and influenced what we write? How has technology diminished my role as the driver of my own writing? The results were unremarkable. ChatGPT produced predictable answers (some of which I had already—predictably—mentioned). There were a few paragraphs about the speed of word processing and accessibility for those limited by poor spelling or grammar. It mentioned slightly off-topic items such as the effects of social media on writing. Interestingly, in response to the prompt about technology diminishing the writer’s role, it told me that too many AI suggestions might give the writer the “illusion” that the machine is directing the narrative more than the writer. Was AI gaslighting me?

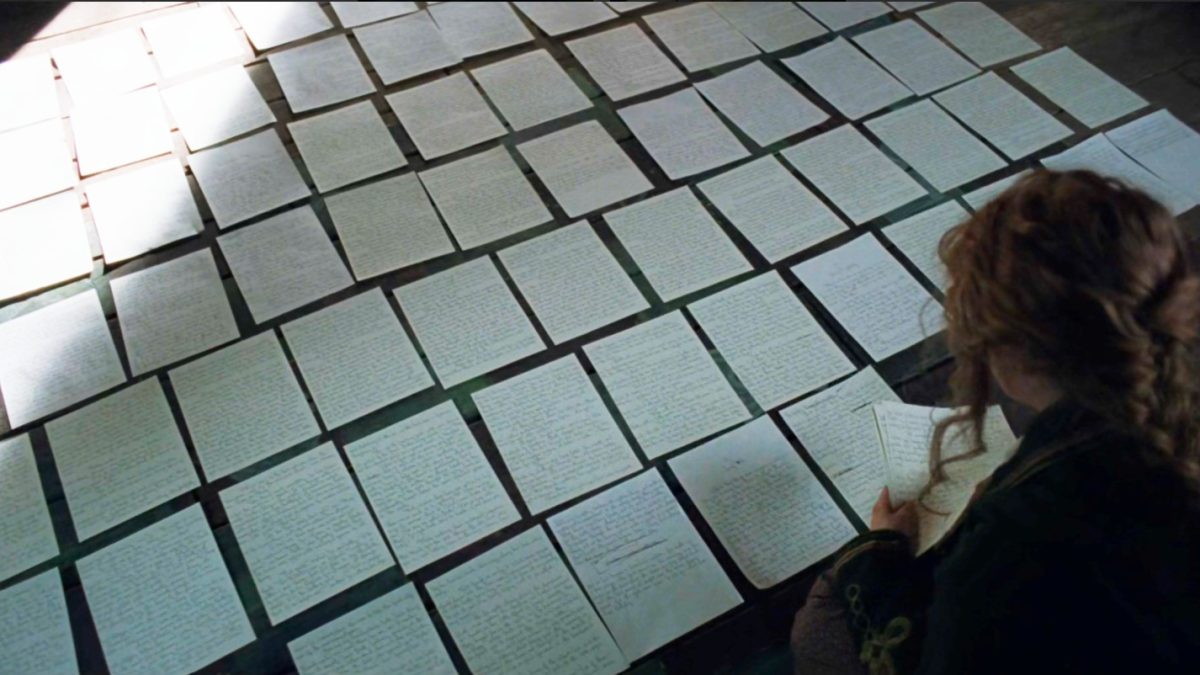

My essay certainly wouldn’t have evolved the same way if I’d begun writing by feeding those few prompts into an LLM. Who knows, maybe I would have ended up writing about social media? What I do know is that absorbing the results of the AI prompts didn’t feel like thinking, it felt like reading. If I’d started with AI-produced paragraphs, the generative process of writing the essay—not just the arrangement of ideas into sentences and paragraphs, but the process of formulating the actual points—would have come instantaneously from the outside. Meanwhile, I spent hours thinking about the topic before and after I started drafting and revising my handwritten essay. I experienced nostalgia remembering the satisfying clunk! clunk! of my old manual typewriter echoing in my childhood bedroom. I thought fondly of the long-ago graduate school days when I covered my living room floor with my term paper pages while trying to organize my thoughts. I pondered other questions, such as how AI might inhibit the development of voice for new writers only just coming of age. The paragraphs I wrote and cut about voice led to more paragraphs that were also cut about a job I had writing advertorials over a decade ago. I recognized the advertorial internet speak in the AI responses to my prompts. I even spent time thinking about the pleasure of improving my handwriting while drafting, relishing the curve of an “S,” the soaking of ink into the page as my pen looped through the script. These reflections don’t appear here—beyond their mention in this paragraph—but they are part of my experience of writing the essay, giving it more depth than any list of AI talking points. This experience demonstrates something basic, something I’ve known from years of journaling but didn’t think much about when I started this composition: writing is a personally enriching process, and it is this enrichment that comes across in the unique quality of what each of us writes. It is the soul of the writing, the thread that can connect writer to reader, which, I believe, is why we write in the first place.

There are all kinds of slow movements: slow food, slow families. Perhaps it’s time for slow writing.

Tech advancement has always asked us to relinquish our skills to machines in exchange for the reward of time. The deal feels worth it in many cases. But as I held my thick and crinkly sheaf of scribbled-on papers, it felt good and satisfying to have that physical product of my labor in my hands. And I wonder if perhaps we’ve gotten confused, thinking we should always use the extra time technology affords to do more things faster rather than using it to do fewer things slower. There are all kinds of slow movements: slow food, slow families. Perhaps it’s time for slow writing. For me, I plan to adjust my writing process by always writing my first draft on paper. This is, in part, an attempt to assert my humanity and wrest my writing from the clutches of technology, but it’s also a return to a process that feels good, takes time, and opens me more fully to the joys of personal discovery and connectedness that occur when words flow onto the page.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.