It was so much easier to hold beauty once I stopped existing.

Article continues after advertisement

Before then, I had spent exhausting years trying to cope with my own embodiment, trying to untangle my gaze from that of everyone else around me. My view of my beauty was rarely mine; it was fed to me by other people, and I believed them because they were the ones looking at me. I existed in their eyes. If my family mocked me for being fat as a child, then that was true. If the cool girls in secondary school ranked me as pretty, then that too must have been true. Beauty was something that was given, and it could just as easily be taken away.

When I was sixteen, I came to the US for college, crashing into a new and hungry gaze, and I learned fast. Beauty was whittling myself down with anorexia and the gasps of college friends at the beauty of my bones through my skin. Beauty was hair whispering past my shoulder blades, straight or not, as long as there were inches and inches of it. Beauty was a formula favored by genetics—clear skin caught in the golden hour, a symmetrical face, even teeth gleaming in a smile. Like everyone else raised as a girl, I was conditioned to believe that some beauties of the flesh were more vital than others. You could be forgiven certain things if you held on to others. You could walk away from one beauty, like an unblemished body, and straight into another beauty, tattoos wrapped around limbs, metal piercing through cartilage. A palace of beauty with many rooms, and I became dizzy as the years passed and I kept falling through doorways. I still wander through a bramble of beauties, resisting some and conforming to others.

When I ask myself what beauty is in my eyes, the answer is that I would prefer not to have eyes.

After I had top surgery, there was no way for beauty to latch itself to my body without another truth attached—that I was deviant and everyone would be able to tell when they looked at me. The bramble thickened, and old voices whispered that thinness would temper it, something that can be controlled, beauty that can be forced. It’s all a delicate balance, especially as a public person, tens of thousands of eyes on you. Some beauties give you power in some palace rooms. Some beauties will make people be kinder to you, less violent. Which choices do you make? Which doorways do you throw your body into? At the end of the day, the standards are rooted in white supremacy, and the world will applaud your bones.

When I ask myself what beauty is in my eyes, the answer is that I would prefer not to have eyes.

I would prefer not to have flesh, I would prefer to be dust, free of the whole thing altogether. I become ensnared by other rooms in the palace, rooms that have nothing to do with me. Yellow strokes of plaster over a wall, speckled green vines, a sun splitting into pieces between twenty feet of waving bamboo. The sky is a riot of pink and blue and clouds, mirrored on a lake so the horizon is consumed. The beauty is my life, that I can see these things. The beauty is that it will all end, and that is the most terrible beauty of all.

Sometimes the eyes are indifferent, mechanical, assessing the body as rudimentary meat.

What could be more beautiful than the sheer vastness of nothing? I would throw away my existence in the effort to experience it, this magnificent promise. I have tried to throw away my existence for it, and even the ritual of that was beautiful, beyond flesh, beyond my gaze or anyone else’s, beyond structures and a cruel society. It was lying in a swamp watching the sky as grams and grams of medication seeped into my blood, reeds and water humming softly around me. I am so temporary, like everything else, and that amplifies the beauty of the void, an inverse reflection of sorts. It all means so little in comparison, a crumbling palace, beautiful because it will die. I survive my suicide in the swamp, and I am reminded that the void is—in the end—an unattainable beauty. By the time I get there, I won’t exist enough to perceive it, which feels right, to only experience the beauty of nothingness by becoming part of it myself. While I live, all I can do is imagine it, dream of it as I wait for it.

I am still never fully clear on whether my gaze on my flesh belongs to me or whether it’s something I ate from someone else, swallowing down their stories. The uncertainty will remain; I don’t exist enough to believe in an essential self. I have beautiful masks that I built up in palace rooms, that I know are beautiful because the audience says so, and doesn’t beauty belong to the eyes naming it? My years of childhood training mean I know how to borrow people’s eyes. In the mirror, sometimes they belong to my mother and brother, or those of strangers, bullies and supplicants both. Sometimes the eyes are indifferent, mechanical, assessing the body as rudimentary meat. All of it is always temporary, dust holding form until it returns to dust. Beauty sifts through my fingers like crumbled skin, and I taste the edge of sublime at the end of a lifetime.

There will be nothing as beautiful as nothing.

__________________________________

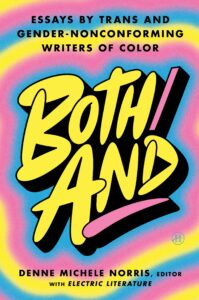

From Both/And: Essays by Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Writers of Color, edited by Denne Michele Norris. Used with the permission of the publisher, HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2025 by Akwaeke Emezi.