CAPITALISM AND ITS CRITICS: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI, by John Cassidy

Given how reliably Americans tend to favor promises of plenty, it has been curious to see a president inherit a humming economy and then proceed to gut the federal work force, start a chaotic trade war and celebrate the scarcity about to ensue. Asked about potential shortages of goods, President Trump has repeatedly offered versions of the same strange example. “I don’t think a beautiful baby girl needs — that’s 11 years old — needs to have 30 dolls,” he told NBC News. “I think they can have three dolls, or four dolls.” (He added, “They don’t need to have 250 pencils, they can have five.”)

Trump makes a few cameo appearances in John Cassidy’s new book, “Capitalism and Its Critics,” for his demonstrated ability to brag about his riches while tapping into growing discontent with the global capitalist system. Some of the critics Cassidy features in this book wanted to replace capitalism entirely; others, like Trump, have sought to preserve a core of self-interest while remaking capitalism’s rules. Rejecting a world financial order fueled by free trade and a bedrock American dollar, the president has been promoting a grab bag that includes both tariffs and crypto — a Trumpian hybrid of the very old and the very new.

But then capitalism has always been a protean force. In the 18th century, merchant capitalism yielded to industrial capitalism; in the postwar era, Keynesianism yielded to neoliberalism. Cassidy, a longtime staff writer for The New Yorker, originally envisioned writing a “shortish history” that began with the collapse of the Soviet Union, but he soon realized that to properly understand the roots of capitalism’s discontents, he needed to go much further back (some 250 years) and write much longer (more than 600 pages).

Despite the obvious differences among the people in this book, they share some complaints. “Over the centuries,” Cassidy writes, “the central indictment of capitalism has remained remarkably consistent: that it is soulless, exploitative, inequitable, unstable and destructive, yet also all-conquering and overwhelming.”

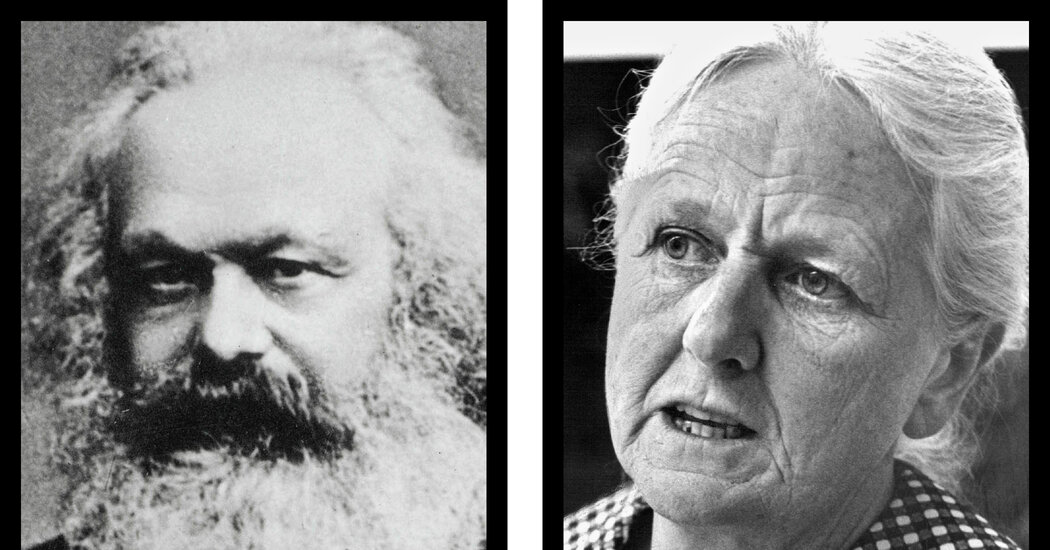

Cassidy begins in the early days of the Industrial Revolution and ends with some thoughts about the economic upheaval that may be wrought by A.I. In between he offers short chapters — 28 in all — dedicated to the life and work of figures both familiar and obscure. The result is an expansive history of capitalism that places less emphasis on economic abstractions like perfectly competitive markets and draws attention instead to how often capitalist systems have fallen short. “It is barely hyperbole to say that capitalism is always in crisis, recovering from crisis or heading toward the next crisis,” Cassidy remarks. In 1857, a financial panic on Wall Street prompted Marx and Engels to believe that a collapse was imminent. “The American crisis,” Marx wrote, “is BEAUTIFUL.” Engels replied, “The AMERICAN CRASH is superb.”

But the state stepped in, as it usually does — averting wholesale disintegration by saving the capitalist system from blowing itself up. This habit of state intervention, of course, runs counter to laissez-faire orthodoxy, with its insistence that markets should be left to their own devices. Cassidy devotes a chapter to Karl Polanyi (1886-1964), the Austro-Hungarian economic anthropologist who argued that free markets were such a “stark utopia” that they required a strong state to lay the ground rules. They were also so disruptive that societies spontaneously tried to reassert some order in response: Writing during World War II, Polanyi described socialism (which he supported) and fascism (which he abhorred) as two disparate reactions to the same capitalist upheaval. As Polanyi put it, “Laissez-faire was planned; planning was not.”

Polanyi was underappreciated in his day, when laissez-faire economics had been discredited by the Great Depression; he was rediscovered in the 1980s, when neoliberalism was ascendant and his grim view of unfettered capitalism served as a stinging rebuke. Cassidy shows how belated recognition was often the fate of capitalism’s critics. The Cambridge economist Joan Robinson (1903-83) was a colleague of John Maynard Keynes, who maintained that the state could get an economy out of a slump by spending money to stimulate demand. Robinson was a Keynesian who nevertheless recognized the limits of Keynesianism. Writing in the 1930s, she theorized about the possibility of unemployment getting so low that bargaining between employers and workers could lead to what was later called a “wage-price spiral.”

At the time, deflation was the biggest threat; it was only four decades later, when stagflation proved resistant to the Keynesian tool kit, that Robinson’s analysis got its proper due. By then she was already frustrated by the state of the economics profession, including the “bastard Keynesians” she accused of simplifying and deforming some of Keynes’s “acid” insights. Toward the end of her life, when asked by an economics student at Oxford if she would have done anything differently, she said she would have studied something more useful, like biology.

Cassidy includes a number of thinkers like Robinson, who attacked capitalism from the left. He also writes about Adam Smith, Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman — each in his own way a critic of what turned out to be a dying order, and who went on to become part of a new establishment. Those who have predicted capitalism’s imminent collapse underestimate its ability to shape-shift into yet another configuration. But stability has always been tenuous: Resolving capitalism’s many contradictions has also meant creating new ones.

The most haunting figure in this book is an outlier: Thomas Carlyle, the 19th-century Scottish essayist, whose assumptions about both capitalism and humanity were so dark that he made no room for the possibility of social progress. He was an avowed racist and antisemite. He thought democracy was hopeless, and evinced utter contempt for “the multitude.”

But Carlyle’s unrelentingly bleak vision, his insistence on hierarchy, his veneration of strongmen, don’t look so out of place in today’s reality. Nor does his ability to attract people who should have known better. Cassidy notes that Carlyle’s admirers included Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. The Transcendentalists thought that Carlyle wanted the same future they did. They thrilled to his excoriations of a soulless “mechanical age” and “Mammon-worship.” They were willing to overlook some of his more unseemly “exaggerations,” Cassidy writes, because, discounting all evidence to the contrary, they believed “his intent was benign.”

CAPITALISM AND ITS CRITICS: A History: From the Industrial Revolution to AI | By John Cassidy | Farrar, Straus & Giroux | 609 pp. | $36