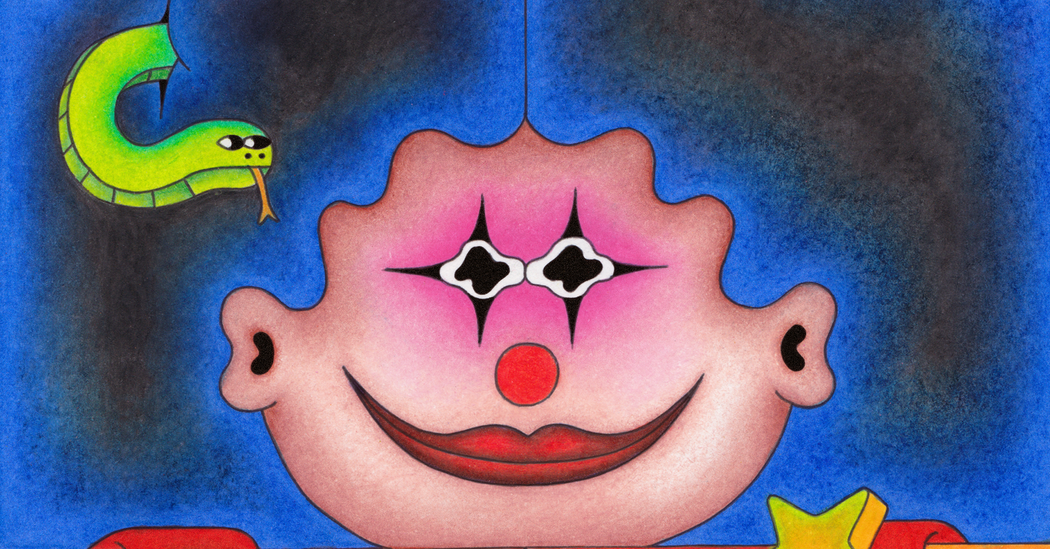

STOP ME IF YOU’VE HEARD THIS ONE, by Kristen Arnett

Some people don’t like clowns. I happen to have married one. My husband was a birthday clown for about four years in the early 2000s, a history that endeared me to the premise of Kristen Arnett’s latest, “Stop Me if You’ve Heard This One.”

Set in Central Florida, the novel follows Cherry Hendricks as she attempts to navigate the vicissitudes of late-stage capitalism. What does that look like? It means she spends her days working at Aquarium Select III, a dimly lit fish and reptile store, while pursuing, in her time off, her true calling: clowning.

Cherry’s clown persona is Bunko, a rhinestone-clad cowboy afraid of horses. She mainly books children’s birthday gigs, but she’s desperate to leave that grind for more full-time clown work. Luckily, there is a big audition for a traveling summer showcase. Cherry believes if she books the tour, it would allow her to “network with half the clowns in Florida” and help her reach the big time.

Then she meets Margot the Magnificent, “one of the most well-respected magicians in the greater Orlando area,” through a dating app. Margot is older and toys with Cherry’s heart, but she may have the professional connections to secure Cherry’s future. Madcap adventures ensue, with a laid-back picaresque pace that still contains the plot elements you’re hoping for: the dangling lure of the big audition, conflict with disapproving family, money problems and some pretty hot lesbian sex.

Throughout the novel, clowns are framed as a way to explore queer identity and gender expression. Bunko is after all a cowboy and is referred to with male pronouns, though Cherry is a woman and referred to with female pronouns. But the way that clowns are reviled by the public at large is also explicitly compared with the queer experience: “Clowning requires a kind of steeliness that I associate with my coming-out process: the knowledge that there will always be people in life who will hate you for who and what you love.”

Clowns have always provided social commentary, whether by making kings laugh at their courts, or by reflecting back to the crowds at the circus their own self-serious posturing. But Cherry is not the scheming, hyper-intelligent court jester figure of Dumas’s “Chicot the Jester,” nor is she meant to be a dark political symbol like Heinrich Böll’s Hans in “The Clown.” If anything, she is closer to The Dude in “The Big Lebowski”: hapless yet lovable, the protagonist while never fully becoming the hero.

Though Cherry has emotional motivations for becoming a clown (she’s grieving a dead older brother who was always the life of the party and their mother’s favorite), she is also interested in the philosophical underpinnings of clowning. Her musing leads to some of the most interesting lines in the book: “To clown well, you must embrace the light smile and the dark heart.” Though her conceptual preoccupation sometimes slows the pace, the nerd in me longed for these passages to go even deeper and provide more technical and historical insight. Clowns are curiously underrepresented in literature, and this is rich terrain.

Like Bunko, Cherry bumbles. A lot. If at times I yearned for her to simply have a better plan, or have a better act, or a better insight, I could also keenly imagine Arnett flopping down on my couch, cracking a beer and saying, “She’s not a heroine, she’s a clown, you dork!” Part of the book’s social commentary is a rejection of success as framed narrowly by capitalism, which also means dispensing with traditional narrative expectations of what the “hero prevailing” might look like.

What Arnett does best, besides set up scenes so cinematic the book is practically begging for adaptation, is ground Cherry in emotional reality. This is ultimately a book about not being loved enough by your mom, and the psychological accuracy of the scenes where Cherry grapples with that deficit ultimately carries the novel.

At one point, Cherry is visiting one of the book’s most lovable peripheral characters, an elder clown and purveyor of clowning accessories named Miri, who is certain that dolls have souls and that how we treat dolls determines how we come back in another life. “I don’t want to come back as something no one loves,” Miri says, a thought that haunts Cherry. If all characters are dolls to some extent, then it is clear Arnett has nothing to worry about: She loves Cherry very much, and by the end of “Stop Me if You’ve Heard This One,” readers will love Cherry too.

STOP ME IF YOU’VE HEARD THIS ONE | By Kristen Arnett | Riverhead | 259 pp. | $28