The Stone Home took me eight years. Set in a 1980s South Korean reformatory center, the emotional and psychological heart of the novel pivots around humanity’s profound immorality as well as the incredible lengths we will go to persevere. It is easier to look away from the suffering of others, easier to reach for lighter fare when so much of the world is crushing devastation. I knew this, yet I felt a pull to tell this story after meeting activist Han Jong-Sun, a survivor of The Brothers Home. He and thousands of others had endured cruelty and pain, so when writing, preserving my own optimism did not seem like a priority.

Article continues after advertisement

When the novel was published last year, the question that threw me the most was: How did you protect yourself while writing this story?

That first time someone asked me, I said, truthfully, “I don’t know.”

The next time, I spoke about Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, where he explains: “When we spoke about attempts to give a man in camp mental courage, we said that he had to be shown something to look forward to in the future. He had to be reminded that life still waited for him, that a human being waited for his return.”

I had this quote at the top of my manuscript, and I returned to it often. As I wrote, I focused on my characters’ friendships and familial ties, so they had a reason to keep their compassion intact. When I considered possible endings, I wanted an honest, hard-won, bittersweet image, one that captured the ways in which we can only survive together.

This second answer, about relying on Viktor Frankl’s quote, is truthful, but it doesn’t capture the full truth because there were many moments, as I wrote through the pandemic and became a mother of two, when I wasn’t able to access this abstract faith.

Only with distance did I realize that in the daily of act of writing, I protected myself through something simple and essential: food.

In my family, as in many immigrant households, food is how we show our care. I love you does not easily pass the lips of my elders, but rather, have you eaten? Growing up, my parents knew intimately my sister’s and my favored foods. At mealtimes, they plucked the choicest flesh of fish and wrapped samgyeopsal in the freshest perilla leaves for us. They regaled us with stories of their younger years in Korea—of the rarity of eating meat or eggs, and when procured, those items were only for the head of the household. See, they were telling us, look how we care for you. When I went to college, I didn’t receive their love in messages stating, I’ve been thinking of you, but rather, in the galbi-jjim my mother prepared for my visits, in the orange juice and jeolpyeon tteok and tabbouli my father stocked just for me. I saw it in the cut pears after dinner, the carefully peeled quail eggs and hours-long simmered jangjorim packed for my return to school.

Like many children of immigrants, I was never explicitly taught that food was our language of love, but rather, shown it in quiet acts, so ingrained into our relations that only in my adult years did I begin to understand its significance. Food was nourishment, yes, but it was also shelter, hope, a gift.

How did you protect yourself while writing this story?

While reflecting on this question, I came to the realization that this way of being extends to my craft as well. Instinctively, as I wrote, I protected my characters from the terrible things they endured by lingering over their meals—the joy and luxury of glistening miyeokguk dotted with sesame oil, or the briny iron bite of jogaetang with their ridged, slippery shells. By allowing my character to slow down, to linger in the sensations, I gave them—and so, the reader and myself—a respite.

The meal doesn’t have to be extravagant. A bowl of hot, white rice. Sugar-sweet straws of Apollo Candy. A slice of sticky gamja jeon. Oftentimes, it is the communal act of imbibing together that is enough. To fully immerse yourself, to pay attention to the meal in front of you is to commit your hope and faith—in your body, in the next day, in our shared world.

Like many children of immigrants, I was never explicitly taught that food was our language of love, but rather, shown it in quiet acts, so ingrained into our relations that only in my adult years did I begin to understand its significance.

In real life, too, the simplest components make the most satisfying meals. One of my favorite comfort foods is white rice swirled with sesame oil and soy sauce. A glistening fried egg on top, the yolk runny, the white edges crispy and curled. A dusting of crunchy, roasted sesame seeds and crushed dried seaweed on top.

Growing up, my mother would make this dish when she was overworked. After catering to the whimsy of customers, she rushed home to more who needed her attention. Some days, when the thought of care-taking was probably too much, she dumped rice into a bowl. With the side of a flat spoon, she’d mash the fried egg until the yolk coated the kernels. This was a dish of convenience, thrown together with pantry staples. But to me, it felt like a special treat. Like a Pavlovian dog, the nutty scent of sesame oil made me come running into the kitchen. The clean, wholesome taste of white rice. The tangy soy sauce cutting through the fat. The richness of a golden yolk, the crunch of crispy egg, the smack of salt from the gim. A side dish of kimchi as the perfect complement. What else could a child need?

I make this dish for my children now, and it is deeply satisfying to see them savor the flavors of my youth. I submerge them with I love yous and kisses, different from my elders in many ways, but hardwired into my understanding of how to be is this offering—that food is memory and care and hope and faith and, yes, protection.

_______________________________________

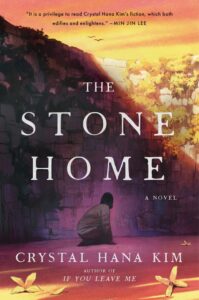

The Stone Home by Crystal Hana Kim is available now via William Morrow Paperbacks.