In Katabasis, two graduate students at a magical version of Cambridge University go to Hell to rescue the soul of their adviser so he can give them a letter of recommendation. Anyone who has spent time in graduate school will understand the joke entailed in this premise, and also the extent to which it really isn’t a joke. Possibly most graduate students who have tried to go into the academy afterward—at least during the past few decades, when the perpetual scarcity of academic jobs has fallen to catastrophic lows—have understood themselves, in one way or another, to be going through Hell in order, as their prize, to get more of it.

This is a novel that plays with two genres at once. On the one hand, it faithfully adheres to what readers expect of romantasy: a genre, hugely popular with the readers of BookTok who can make a book a bestseller, that combines romance plots with fantasy settings. On the other hand, it’s a satire of academia in the vein of David Lodge, Elif Batuman, or, especially, Susanna Clarke.

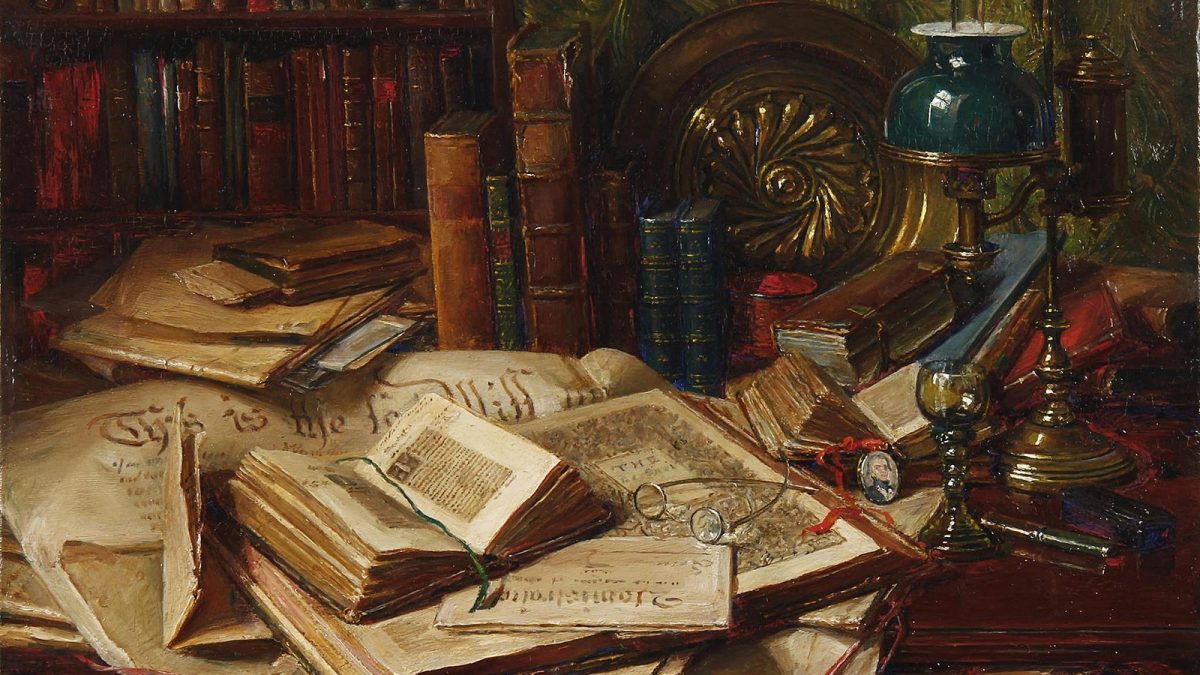

Which places the novel in the interesting position of drawing from a specific experience but being marketed primarily to readers who haven’t had that experience. The aesthetic called dark academia—which, for reasons we’ll get into, is the frame through which readers on social media will likely encounter the book—is one of the fastest-growing categories in publishing. The term only started appearing in deal announcements on Publishers Marketplace in 2022, but it has already accrued a long shelf of titles, including Donna Tartt’s The Secret History (retroactively), Leigh Bardugo’s Ninth House, M. L. Rio’s If We Were Villains, and Kuang’s own Babel. It also pervades TikTok, Tumblr, and Instagram hashtags. Think Gothic corridors, gloomy libraries, deadly secret societies, marble busts of authors watching you with knowing eyes.

Generally, the dark in dark academia refers to safely improbable things, like murder. Some people theorize that the appetite for dark academia started with the Harry Potter books, which gave young readers a taste for old stone dormitories, magical books, and late-night study sessions in the library’s Restricted Section. Regardless of whether that’s true, it is true that dark academia tends to present a vision of academic life that has far more to do with fantasy than reality. Dark academia is magical, murderous, melodramatic. It tends to be interested in Gothic questions, like whether we can bury a sin for good. The characters don’t care about the particularities of the academic job market. They’re more interested in questions like who murdered their classmate and whether the evidence points to a poisoned book or the necromantic rituals of a secret society.

But Kuang uses the confluence of these elements—romantasy, academic satire, and dark academia—to pose a more interesting set of questions. To wit: What is the magic that scholars find in the academy? (Kuang holds degrees from Georgetown, Cambridge, and Oxford, and is currently taking a PhD at Yale.) What are the wrongs they’re asked to quietly endure—the things that make academia, so to speak, dark? And is the magic worth the darkness? Her novel has the obligatory murders, but there’s an allegorical resonance that comes from its setting in an academic world that graduate students and professors would recognize.

For instance, the adviser the protagonists seek is a celebrity scholar who enjoys seeing his advisees suffer, plays them against each other, and likes to remind them that without him, their careers are nothing. (We’ve all met the type.) Kuang’s magical Cambridge includes impoverished graduate students, professors who place their own names on papers their students wrote, sabotage, snobbery, sexual harassment, and bureaucratic machinery that readily crushes whoever gets in its way. Magic is, in fact, just another academic discipline there, like philosophy or literature; and, as in those disciplines, graduate students are so desperate to get one of the few tenure-track jobs that they’re willing to walk through fire. The protagonist, Alice Law, reflects on her situation in words that would fit in any of those unhappy essays that former tenure-track hopefuls write when they leave the academy: “She had trained her entire life to do this one thing, and if she could not do it, then she had no reason to live.”

If the devotion scholars feel toward their work is intense and sometimes irrational, it’s because this is one of the last spaces of unalienated labor. It’s precisely because the work is so powerful that younger scholars are willing to put up with bad actors for the chance to keep doing it.

The magic system is based on how academia works. Magicians work with the hermeneutics of interpreting statements and philosophical problems; if the interpretation can be jinked in such a way that the impossible seems possible—even for a moment—then the impossible will happen. (It’s the old author’s boast: fiction is magic.) Their methods of doing this split them into factions as quarrelsome as the panels at an MLA convention: “Over in America, visual illusions and flashy showmanship were all the rage. In Europe they were going on about things called postmodernist and poststructuralist magick, which seemed to involve lots of spells doing the opposite of what their inventors wanted, and spells that did nothing at all, which everyone claimed was very profound.”

That someone can only be a magician if they work in academia may seem odd, given all that magic has the potential to do. But that’s how it is in our world, too. Literature professors, for instance, think of what they teach as sublimely important, but most literature majors wind up in a corporate world that can find no better use for their talents than improving a brand’s SEO strategy. Some magical-PhD holders stay in the conversation, so to speak, by becoming hedge witches, but it’s the same lonely office as being an independent scholar.

And yet the magic, in the novel’s world as well as our own, is very real. Because of the nature of the magic system, every time the characters use magic, they experience it as if they were making a surprising connection or devising an elegant argument. And “the profession”—as people in academia call it, as if to suggest there is no other profession—has other enchantments, besides: the moral groundedness of doing work that might matter; the satisfaction of a really good teaching day; what historians call “the pleasures of the archive.” If the devotion scholars feel toward their work is intense and sometimes irrational, it’s because this is one of the last spaces of unalienated labor. It’s precisely because the work is so powerful, in fact, that younger scholars are willing to put up with bad actors for the chance to keep doing it.

The magic is also in the references. In the world of Katabasis, all the great stories about journeys to Hell, from Orpheus to Dante to T. S. Eliot, are nonfiction accounts that can serve as Baedeker guides for living travelers daring the same descent. Characters talk about literature and mythology constantly, which makes sense, given that any work of fiction in our world might be nonfiction in that one. And allusions wink at us above the level of the plot: the protagonists’ names are Alice, suggestive of the girl who fell into Wonderland, and Peter, suggestive of the original lost boy.

In short, the novel treats literature as a lived-in place—as it feels when you’re young enough to believe all the stories, or old enough to believe them again. (I won’t tell you how the book ends, but if you’ve read Paradise Lost or Dante’s Inferno, you know the words it ends with.)

As a satire, the novel covers plenty of academic absurdities and offenses, which readers might interpret, variously, as peccadilloes or contrapassi or minor infernal torments. In the “Pride” circle of Hell, for instance, a dean lists some of the sins that brought souls to that lesser ring: a reviewer who turned down manuscripts that didn’t cite him; a scholar who claimed to work at Oxford, when it was really Oxford Brookes; a medievalist who “made his wife call him Doctor.”

I assume the novel was written with the expectation that academics, taking the bait to treat it as a roman à clef, would amplify the conversation by quibbling over such details, which I’ll do here: I’m convinced that, in real life, the sin the professor would commit against his wife wouldn’t be having her call him Doctor, but having her work on his dissertation without giving her credit. The other sins I’ve seen. And others still: visiting fellows from outside academia who quickly update their bios to say they “teach at Prestigious University” and never update them again; archivists who growl and snap at the gates like Cerberus; undergraduates who campaign to change their grades with all the calm and wisdom of a pro se litigant.

If that were all one had to endure, the joke of the novel’s basic conceit wouldn’t land with nearly as much impact. But we all know how the soft snow of silence in this business covers over real exploitation, real abuses of power. A few pages in, there’s a piece of withheld information that made me think the adviser had committed what Americans call a Title IX violation. You’ll have to read the book to see if I was right.

And yet—Kuang very obviously loves this place, too. Like Milton, who can’t look at Eve in Paradise Lost without falling in love with her, Kuang can’t look at Cambridge without being in love with it. Or maybe a better comparison is the moment in the Iliad when the Trojan council of elders, who have seen their city ground down under a nearly decade-long war for the sake of Helen, see her approaching the city’s walls and say to each other, effectively, “I get it.”

When the protagonists first get a good look at Hell, for example, they discover that it has bent to the shape of their own “moral universe,” just as the Hell of Dante’s Inferno reflects the moral universe of 13th-century Florence. But whereas Dante saw stinking swamps and bleeding trees, reflecting his idea that suffering in Hell is just the sin itself without the illusion that made it desirable, Kuang can’t help but look with desire, even here:

So perhaps they should have expected, then, for Hell to take on a most familiar landscape: Gothic towers, courtyard walls, and winding between them, a single paved path—just wide enough for pedestrians and cyclists, not wide enough for cars. You always knew, stepping into such places, what they were for. You knew precisely where you were from the uniformity of design; the same shades of brick and stone across buildings. You knew from the lack of wide streets and shop signs; from the quiet absence of children. You knew from the arched gates that marked the boundary. Fairy gates, signaling departure. The mundane world ended here. These were not places of leisure or business. These were places to be still, to think, and to step out of time.

“Christ,” said Peter. “Hell is a campus.”

As I mentioned, the challenge that the author has set herself is to combine a satire of a very specific world with a genre novel for a much larger readership. It’s also a younger readership than the one David Lodge, for instance, wrote for, and therefore less likely to be familiar with the academic labor system. In Lodge’s time, genre fiction was written to be bought in airports or at the grocery store checkout. In the 21st century, it has undergone a consumer revolution, thanks to the rise of reading communities, mostly women in Gen Z, who talk about books on social media—the younger sisters of the readers Janice Radway discusses in her 1984 classic, Reading the Romance.

These communities are powerful—so much so that they’ve changed the very way books are made. Now book covers are designed to stand out on a phone screen, not just in the hands. Bookstores are putting out tables showcasing story categories that Gen Z is intimately familiar with, but that haven’t yet made it to the labels on the regular shelves: romantasy, cozy fantasy, dystopian romance, dark academia. In 2021, Shannon DeVito, a senior director at Barnes & Noble, told the New York Times that success on BookTok can mean “crazy sales—I mean tens of thousands of copies a month.”

Genre is a suite of expectations on the part of readers. Accordingly, this book indulges the reader with a charcuterie of BookTok bait. By page five, we’ve squarely hit the trope “enemies to lovers.” After that, we soon hit “look at me” (a trope in which one character says these words to another having a panic attack), “only one bed,” and “fake dating.” Then we get “look at me” again, this time reversing the speaker and the listener.

Likewise, the book’s presentation and marketing aim, in part, for that BookTok audience. Influencers are on the media list to receive galleys. The launch campaign will include a “deluxe limited hardcover” with illustrated fore edges—which is going to look great on Instagram and TikTok, where content creators will hold up the book for the camera and recite the story’s tropes. (These also include “slow burn,” “second-chance romance,” and “he falls first.”)

Kuang is doing well: she’s a New York Times best-selling author, and already, at 29, the kind of high-profile author whose name appears in book-deal listings as a selling point—“Pitched for fans of R. F. Kuang.” The galley of Katabasis was as hard to get as a Sally Rooney galley.

Will her Gen Z readers be interested in the question of whether the magic of academia is worth it? If she’s done the job that a novelist is supposed to do, they will. She may even inspire some of them to go to grad school—an offense for which, if there is justice in the afterlife, she will certainly have to put in some time in Purgatory. ![]()

This article was commissioned by Leah Price.