I had been spending more time teaching at the essay cram-school and working at the coffee shop than writing. There was nothing I found more challenging than dealing with people, and yet everything I did to earn a living involved interacting with hordes of random people all the time. Working all day among people I didn’t know reduced my soul to a withered bit of spinach rotting away in the back of the fridge. I’d come home, shower, have two shots of soju and go out like a light. Then I would wake up before dawn and write.

I never thought the day would come when I would make a living solely from writing. This never occurred to me while I was writing that novel, or when the publisher picked up my novel for publication, or when the novel came out as a beautiful hardback.

Six months after the book came out, I quit the coffee shop. I was receiving commissions for the first time since I became a writer, which left me no time for the part-time job. A couple of months later, I quit the essay cram-school as well. The head of the school wanted to use my activities as a writer to generate publicity for the cram-school. There was nothing strange about a writer teaching how to write essays, but the sort of writing I taught was so different from the sort of writing I wrote – it was best that I quit before feelings were hurt. Besides, I was more than able to live off the royalties alone by then.

The novel wasn’t awfully progressive or radical, but it landed in the crosshairs of so many disputes. A middle-aged male actor read it, recommended it and was heralded as a feminist; while a young female radio-show host who introduced the book on her programme had to post a statement of clarification on social media, and then turned the account private when the attacks continued. I have to admit that this increased circulation and sales. Which gave rise to more disputes, more sales and even more disputes, in a cycle that was either vicious or advantageous – I can’t decide.

In the meantime, I was making enough to afford a personal trainer, underline passages in books and magazines I could now buy rather than borrow from the library, and have daily seasonal fruit I used to put back after checking the price. And I worked up the strength to write more. I can’t decide if this was a vicious or advantageous cycle, either.

I was being published, and I was given a voice. I believed there was strength in the written word and that there were certain things I ought to write with a sense of responsibility. I was afraid, lonely and disappointed more often than not, but I kept reading, thinking, asking questions and leaving a record whenever I could.

But hostility hit harder than kindness. Things I never said were printed in double quotes in interviews, and sentences and scenes that were not in my novel came up in online reviews. In the end, I gave in. I’m being used – the thought I’d been desperately keeping at bay came over me, and in that moment I knew I’d been broken. I took a wrong turn in my red shoes. My feet danced a jaunty jig as I wept copious tears. I had but one goal: get out of these shoes.

I accepted the Yonju University lecture at a time when I was declining all commissions and favours. It wasn’t for old times’ sake or out of gratitude for the teacher who comforted me when I was a girl, but to return the book to Ms Kim. And with it the message that I’d made safe passage through the bleakest days of my life thanks to this book.

The lecture was announced on the Yonju University website and Facebook page, and the first comment was, ‘I hope you die on the way here.’ I was afraid of getting egged on stage. I got on the Mugunghwa train to Yonju with Ms Kim’s copy of Bird’s Gift, so brittle that a firm grip might have broken it apart, a more recent hardback edition of Bird’s Gift with a new cover and a box of assorted cookies. And I vowed I would never again give another lecture.

*

No one egged me. The small auditorium filled up and I finished the presentation sooner than I’d planned, but the Q&A session ran over and the event ended far later than expected. I think I signed books for about an hour as well. I chatted with some people as I signed their books. Some were from neighbouring universities. I got nervous and embarrassed after the fact to know that quite a few literature and writing professors were in attendance as well.

Ms Kim, two students who were fans of my novel and I went out for a late supper. Ms Kim, who was sitting in the car’s passenger seat, half turned to the back seat and asked, ‘Choa, ever tried fish noodles?’

‘Fish noodles? I’ve had seafood noodles.’

‘Haha, it’s nothing like seafood noodles. This is more like fish porridge. Spicy and thick. It’s a local delicacy here. Try it.’

Bingeo – a kind of smelt fish – fanned out in a circle and fried on an iron pan, was placed in the centre of the table, and we each got our own bowl of fish noodles. I’d only seen these dishes on TV. The fish noodles were not as fishy as I anticipated, but quite hearty with a decent amount of meat. The fried fish served with sweet and spicy sauce was scrumptious to say the least.

We ordered soju at first. We’d finished two bottles when one of the two students had to go. The student wanted a picture with me, but I was too red in the face, so took a rain check. But I offered to sign her copy of my book. The pen kept slipping in my hand. I wondered and worried if I was that drunk already.

Ms Kim ordered another beer and soju. She filled a beer glass halfway with soju and poured a small layer of beer on top.

‘Don’t stir and take a big sip. It’s sweet.’

No way. She handed me the glass and I took a sip. It was sweet. I looked at the glass, took another sip and cried, ‘Wow! Wow!’ I was pleasantly drunk on the sweet concoction when Ms Kim said she had a confession to make.

‘You know, I didn’t lend you that book.’

‘Huh? Book? Bird’s Gift?’

‘That’s the one. You got it wrong, Choa. You were talking about the day Kim Seongtae hit you, right? Summer session?’

‘Yes.’

‘I did take you out to the hill behind the school. And since you were in my class first period, I went back in and told you to go wash your face and come back when you were ready. And you came back later with the front of your shirt soaked.’

I did? I don’t remember. But I did get slapped by the Dean of Students one day during summer session in my senior year, and it was Ms Kim who took me up to the hill and comforted me. I guess the Dean of Students was Kim Seongtae. And only I remember borrowing Bird’s Gift from her, just as only she remembers me showing up in class with my shirt wet. I felt dizzy. We ordered more beer, soju and fish fries. Lots of loosely interconnected stories were exchanged in succession.

I asked if she had family in Yonju and she said, ‘No, which was all the more reason to apply to Yonju University.’ And she added matter-of-factly, ‘My father hit me.’ He hit her less and less as she went through adolescence and he hadn’t hit her once since her coming of age, but she still remembered vividly. The tension and pain, the terror and sadness.

‘Maybe that’s why I pulled you out of there that day. You reminded me of myself, the way you were standing there with your cheek glowing red. I was like that, too. I would apologise and promise never to do it again, cry, beg, plead. But when I got hit – smack! – I just froze. Not another word, no more tears.’

Ms Kim’s younger sister left home for yet another set of fetters called marriage; Ms Kim fought to protect her powerless mother and ultimately ran away from her entire family. Her father’s violence came from his ineptitude, she now knew. Each time things went wrong outside the home, he turned into a despot to confirm that he was still master of his household. Ms Kim confided a few memories about her father and I just listened. I didn’t ask questions or share my own stories in return. I was hurting.

‘That’s enough alcohol for me! The things I’m saying to a student!’

‘I’m not your student anymore.’

‘That’s right. I checked your bio on the book jacket and I was shocked. We’re only eight years apart! We’re both in our forties now. We’re getting old together.’

Ms Kim cackled, her shoulders heaving. I couldn’t laugh. She gazed at me and told me not to worry because she was content with her life now. I told her I was glad.

It was past three in the morning when we left the restaurant. Ms Kim invited me back to her place, but I didn’t feel comfortable and didn’t want to impose. I said I’d hang out at a café, or at Lotteria near the station, and catch the first train back at six. Ms Kim laughed, shoulders heaving again.

‘Nothing’s open now. This isn’t Seoul. There are no 24-hour coffee shops and burger joints around here. Come with me if you don’t want to sleep at the train station like a hobo.’

Without meaning to, I woke up at her place past noon and we went out for hangover soup together.

__________________________________

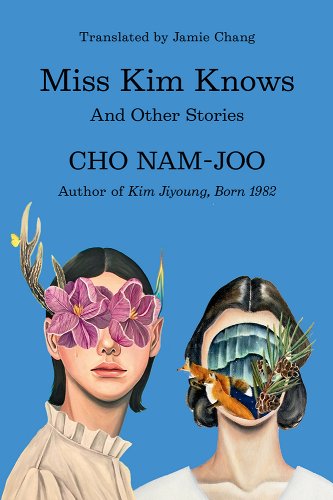

From “Dead Set,” excerpted from Miss Kim Knows: And Other Stories by Cho Nam-Joo. Copyright© 2021 by Cho Nam-Joo. English translation copyright© 2023 by Jamie Chang. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.