There is nothing more emblematic of American freedom than a car. Especially for me, growing up in a small town in the middle of nowhere. A driver’s license was synonymous with autonomy, and the first thing I did with my autonomy was to run down my family’s mailbox. I remember asking my father why he didn’t holler at me to stop as I backed out of the driveway. I have since learned, with or without the mailbox, the letter always arrives at its destination. My first car was his maroon stick shift Subaru Outback, a gay foreshadowing that I now cherish. When I failed to convince my parents to let me get a motorcycle at age 16, we compromised on a brown 1978 VW bus from a retired Santa Fe hippie. And later, in my early 20s, I became fixated on buying a white 89 Toyota pickup off Craigslist—the same make and model as the one a fleeting highschool boyfriend had. It was essential and urgent that it be the same color as his; solidifying my earliest expressions of masculinity through haunted mimicry where the smell of gas and closeted teenage sexual encounters intermingled with the sounds of radio country parked in an empty cul-de-sac that butted up against White Rock Canyon.

Article continues after advertisement

The only thing that could transport me as far away from my small town as much as my car was literature. As a kid, the promise of the freedom depicted in road trip novels genuinely impacted me. You can’t blame a closeted teenager for loving On the Road. You just have to beam at them in your memory. I read about highways through the sweet and dangerous lens of nostalgia: the road novel aesthetic ballooned so urgently that there was no material cost too high to justify how my car operated in my symbolic world. I guzzled gas, I blasted the same songs on repeat, I shifted smooth. My insurance was still cheap, backseat full of trash. I was on my own time, I went fast, I went everywhere. I was free and continued to be. My car was the symbol of freedom, and, as one does, I drove my symbol into the ground.

I sought out to find a poetics of cars and death/drives, asking what form could convey the tragedy and cost of our lived experience of the bound reality of freedom and unfreedom.

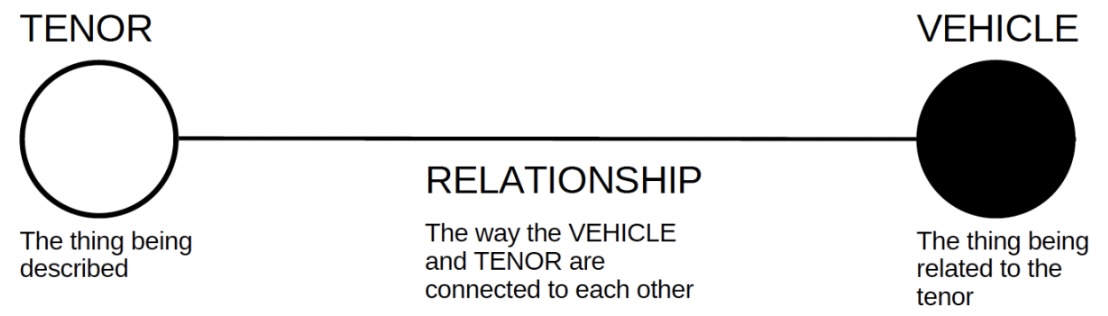

In school, when I first learned how the structure of the metaphor—the modus operandi of symbolism—worked, I was thrilled to find, even there in English class, my car. Most American students are taught metaphor via the heuristic developed by rhetorician I.A. Richards, who describes it as having a two part structure: a “vehicle” (is the figurative language used to describe something else) and a “tenor” (the thing being described). “Tenor” is Latin for continuity or a holding of course—and the “vehicle” is what carries us there. Developed as the primary way of teaching metaphor to rhetoric students in 1936—amidst the boom of “petromodernity” and the rise of the individual automobile—Richard’s use of the word vehicle has always haunted me. A car metaphor to describe a general structure of metaphor? How can the most popular way to make sense of metaphor—the bread and butter of poetry—be by comparing it to a car?

Having moved on from road novels to poetry, and above all obedient to the logic of the pun, I began my quest into how poets write about cars. In Bertolt Brecht’s “On Form and Subject-Matter” (1957) he asks “Can we speak of money in the form of iambics?” With the rise of petroleum as a commodity that organized an increasingly globalized world, he argues that “petroleum resists the five-act form” and “today’s catastrophes do not progress in a straight line but in cyclical crises.” Writing from the heart of the smoggy car city of Los Angeles, I followed this Brechtian prompt to ask what aesthetic forms could say something about the consequences of petromodernity 100 years later, as we live and drive toward climate collapse and the car’s obsolescence. I sought out to find a poetics of cars and death/drives, asking what form could convey the tragedy and cost of our lived experience of the bound reality of freedom and unfreedom, of the tenor and the vehicle.

I began with the story of Orpheus: iconic, sexy, ancient Thracian poet, who was refigured in Jean Cocteau’s Orphée in 1950, as having an obsession with a car. In the film, Orpheus, the famed poet, falls in love with Princess Death, who notably rolls up in a Rolls-Royce to the Café des Poétes in the middle of a brawl. Amidst the chaos, she (Death) doms both the poets and the cops at once, has her murderous henchmen (motorcyclists, my parents told me so) kill one of the young hot, existentialist poets Cégeste, and then demands Orpheus come with her to escort him to the underworld. Orpheus has no idea what is coming, and upon sliding into the backseat of the Royce with Death and her recent corpse, begins a journey where he will traverse between the living world and the underworld, all mediated via the car. Once returned back home to his wife Eurydice, Death transmits fragments of surrealist poetry to Orpheus through the radio of the Royce. Orpheus becomes obsessed with the transmissions (read tenor), and spends days in the car parked in the garage of his house attempting to capture and decode the poetic messages. He cannot drive. He cannot leave the driver’s seat. Cocteau’s reimagining of the Orphic myth locates his love for Death as just as irresistible as Euridyce, his wife. Euridyce is constantly trying to get him to pay attention to her, but Death and her poetics is all he longs for. “Orpheus,” Euridyce complains, “Nothing matters but this car.” Which is to say, nothing matters but Death. Nothing matters but the drive. Princess Death drives on.

Still from Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (1950).

Still from Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (1950).

According to Lacan’s update to the Freudian psychoanalysis, all drives operate at the speed of the death drive. The death drive is a mistaken longing for pre-Oedipal harmony that fuels the coherence of our symbolic order, mediating between life and death. But as every Orphic driver knows, this has more to do with our quest to cohere meaning in our symbolic worlds than biological instincts. For better or for worse, the drive is a series of detours that lets us speed toward and circle around the enjoyments of life that we, in a world that is literally running out of gas, don’t have the energy for. Not literally death, but the deadness we intercept driving close to the guardrails. The drive circuits around what keeps us alive, beyond mere self-preservation. The proof is in the poetry: the death drive, actually, is on the side of life.

Jack Spicer, a severely melancholic California poet whose own death drive ended tragically, left us with exquisite Orphic car poems in his wake. Spicer writes about Orpheus’s Hell in “Car Song” (1962): “Away we go with no moon at all. / Actually we are going to hell,” he writes. “We pin our pins to our backs and cross in a car / The intersections where lovers are. / The wheel and the road turn into a stair.” He concludes the poem with a prosaic note explaining the verse: “Intersections” is a pun…The stair is what extends back and forth for Heurtebise and Cegeste and the Princess [Death] to always march on.” Spicer’s hell is traversed literally via the Orphic Car and, like Orpheus glued to the car’s radio transmissions from Hell, Spicer famously invokes “dictation” from an always-outside source (A Martian, he says) as the source and inspiration of his poems. For Spicer, as for Orpheus, without the car’s mediation, there would be no poems. Nothing to live (or die, or drive) for.

In early May I drove back to LA from a reading in the Bay listening to Jonathan Richman’s song “Roadrunner” on repeat. Joshua Clover had just passed and we were all grieving. I spent the week reading his poems and landed lastly on Roadrunner (2021)—a book about the Richman song about driving around the beltway around Boston—its own Brechtian cyclical crises, which is a really different experience than driving down the I-5, but in the structural context of capital, not so different at all. Clover situates Richman’s Boston circular Route 128 “within what is for me the true metanarrative of the U.S. present: the catastrophic trajectory of capitalism.” And driving down the I-5, listening to Richman singing about listening to the radio to feel less lonely at night, feeling myself less lonely as the sunset to the left of downed almond groves and fields of pumpjacks, I gunned it through the cyclical catastrophic trajectory of capitalism. The whispers of the dead bugs slamming against the windshield of the dead labor—(Marx’s own metaphor to describe the labor crystalized in the commodity) crystalized in my most dependable commodity that I cannot live with and cannot live without. My symbol, my trap—my car.

I don’t drive a Roadrunner like Richman or a Rolls-Royce like Orpheus. Now, I drive a 2013 Prius-C with a dented bumper and cigarette holes burnt in the roof from when it was stolen out of poet Carla Harryman’s driveway in Ypsilanti, taken for a 3 month joyride, before being returned to her and then sold to me for my cross country drive to move to LA. The car would be utterly dysphoric—as all Priuses are—if it weren’t for this lore, and it was an act of embracing my adulthood to sell my latest baby blue 1981 Datsun pickup with zero power steering (symbolic) to give up the show and buy a reliable car. This is the car I sit in as I commute around the LA interstates, whispering my favorite mantra to myself: Rosie, you aren’t stuck in traffic, you are traffic. “And my other favorite mantra” to “And my other favorite mantra; to live is to drive, which is a line from Wanda Coleman’s poem “I Live For My Car” (1985). In it, the poet laureate of LA, royalty of the Watts Writers Workshop and embittered romantic lyric of state violence writes: “can’t let go of it. to live is to drive.” Coleman’s car poem is tongue-in-cheek quintessential LA: an ode to the vehicle that at once enables connection is the same thing that keeps us as separate individual nodes in a driving city. For Coleman, it’s what she pours her money into to keep it running at the expense of making rent, it’s the location of her fantasy, her identity, and is her revenge. “i have frequent fantasies about running over people i don’t like / with my car,” she writes. “my car’s an absolute necessity in this city of cars where/ you come to know people best by how they maneuver on the freeway / make lane changes or handle off-ramps.”

Coleman wrote from a position of Black single motherhood and multiple jobs in the 1970s post riot landscape of Los Angeles. To love is to be a commuting soldier, to fight to traverse the tragedy of loving amidst the tragedy of racial capitalism, to hurtle toward freedom in a death trap going 60mph. But Coleman’s insistence on loving her car makes it clear it is explicitly not a metaphor—it’s the real thing—the Ur-commodity of the Angeleno. Compensating for its daily depreciation with the repetition of appreciation, Coleman almost succeeds in turning its exchange value into use value. As if her love for her car could reclaim the commodity from how it circulates in capital, from how her body is alienated as living labor, getting from home to work to home again, kids in the backseat. Instead of God, she prays to the mechanic that the AC works, tuning the spark plugs and lug nuts to keep her mobile. In a final inversion she writes, “I live for it. Can’t let go of it/ to drive is to live.” To live is to drive, to drive is to live. Coleman’s freedom and unfreedom is bound to the car.

In talking about Roadrunner in an interview in The Paris Review in 2021, Alex Abramovich, Joshua Clover speaks to the car as a symbol of (un)freedom in American Literature. “You are free at the wheel of your automobile because of a complementary unfreedom, which is, to simplify, the person working in the auto factory,” he writes. “When you buy the car you are purchasing their misery. And the important thing is, the driver and the factory worker, one circulating through the world of consumption with its pop songs and Stop & Shops, one immobilized in the world of production with its assembly line…these are not different people, despite what they tell you in Econ 101. They are the same person, it’s just a different time of day.” Coleman’s poems echo. Sardonically reclaiming not only the commodity but the commute from the logics of capital, Coleman’s tone takes the contradictions of capital by the throat and pins it against the wall. Can’t let go of it. Like the poet needs the car to make her metaphors work, the worker needs the car to get to work and back.

The poetics of the car drive us through death and back: to grapple with the tragedy and truth that there is no outside to the darkness that surrounds in the form of capital, nor the repetitive teleology of the death drive.

Poet Phillip Levine, who started working in Auto factories as a kid in Detroit in the 1930s, puts it most straightforwardly in “What Work Is” (1991): “We stand in the rain in a long line/ waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work.” Which reminds me of one of my other favorite lines in American poetry “The pure products of America/go crazy–” writes William Carlos Williams in “To Elsie” (1923). Williams laments the devastation of destitution under capital, concluding the poem with the lines: “No one/to witness/and adjust, no one to drive the car.” Robert Creeley famously makes a similar assertion in a far different tone. In “I Know a Man” (1991), another parodic invocation of car-as-solution for the fucked up world we live in, he asks: “The darkness sur-/rounds us, what/can we do against / it,” To which he answers his own question with the bravado of exhaustion “or else, shall we & / why not/ buy a goddamn big car.” In “Homage to Creeley” (1959), Spicer plucks up Creeley’s goddamn car and inserts it back into the Orphic hellscape. In the explanatory note following the poem he writes: “The car is still travelling. It runs through the kingdoms of the dead picking up millions of passengers.” Speeding down the I-5 passed the stench of the massive cattle farms and the haunted site of downed almond tree groves, I meditate on these kingdoms of the dead—that metanarrative of U.S. capital as embodied by the extracted and depleted Central Valley. The car is both the most precise embodiment of American capitalism as Williams laments, and an exhausted turned euphoric answer to how we get where we are going. A small goddamn second hand Prius once rightfully stolen—liberated from the chains of exchange—alone careening through an apocalyptic Southern California landscape.

But like Levine’s line, the bleakness of the Central Valley death drive brings us so close to the contradiction of capital, precisely where we cannot turn away from it. At the end of Levine’s “What Work Is,” he paints a scene of standing in line in the rain at the auto factory waiting for work. Looking ahead, he mistakes a colleague for a brother—when “You love your brother, / now suddenly you can hardly stand / the love flooding you for your brother.” Only those standing in line for work mistaking their underemployed coworker for their brother can know this feeling, the poem argues. If you haven’t told your brother you love him recently, it’s not because “you’ve never/done something so simple, so obvious, /not because you’re too young or too dumb,” he writes. “No,/ just because you don’t know what work is.” Levine’s love in the auto factory line is the same love that Coleman has for her car: to live, to love in and through the trap of capital and its commodities. Nothing matters but this car.

The poetics of the car drive us through death and back: to grapple with the tragedy and truth that there is no outside to the darkness that surrounds in the form of capital, nor the repetitive teleology of the death drive. But who else but to deliver us a rallying cry that takes us beyond the border of the poem than Diane Di Prima’s (who, according to her friend David Levi Strauss, drove a “rattletrap little red death car”) “Revolutionary Letter #16” (1971) when she asks: “do we need cars, when petroleum pumped from the earth poisons the land around for 100 years, pumped from the car poisons the hard-pressed cities?” The question isn’t rhetorical, and she answers it in “Revolutionary Letter #34” (1971), saying No, instructing us not, in fact, to get a big goddamn car in the face of existential and capitalist dread, but instead, to “BLOW UP THE PETROLEUM LINES.” The goal is how to not let Death seduce us into thinking it will win. It is how to forgo the Rolls-Royce of metaphor and find our way to tenor—to being held continuously. Can we free the car from its status as vehicle in favor of its materiality? Use it for the purposes of the tenor—of carpooling our lonely American bodies to each other to blow up the very thing that shapes our life. Cathect not just to Orphic death, but to the drive. Find solidarity in kissing our brother’s in line for work. As we drive to live and live to drive, may we find a poetics that compels us to use our death drives to invoke the explosion of revolution that might transform our petromodern society on the cusp of climate collapse. May we do what Creeley implores and “for christ’s sake, look out where yr going.” And may we, like Orpheus, transmit the poems of those we have lost, singing along with Clover to Richman’s lonesome velocity, with the Radio on.

__________________________________

Fuel by Rosie Stockton is available from Nightboat Books.