It’s been thirty-two years since Eric Drooker published his groundbreaking tale of destitution in the city, Flood! A surreal, wordless graphic novel, Flood! was inspired by the work of woodcut artists Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward, Jungian psychology, and the pitched battles Drooker witnessed in his native East Village between police and the working-class activists who would not be silenced. A 1988 Tompkins Square Park protest in which Drooker took part appears in the final pages of Flood!, where jazz musicians and a powerful barefoot woman face off against club-wielding police on horseback.

After Flood!, Drooker collaborated with Allen Ginsberg on Illuminated Poems, drew the art for Howl: A Graphic Novel, and published Blood Song, a dreamlike account of a young woman’s journey from a jungle paradise to a dystopian urban world. Throughout his career, Drooker has stayed true to his activist roots. The latest in his long line of political posters, “Ceasefire!”, featuring a Palestinian child shouting for freedom, can be seen in apartment windows and shop doors around the San Francisco Bay Area. And in his thirty-five New Yorker covers, Drooker has tackled issues ranging from gun control to racism to climate change in his signature vivid, kinetic style.

As Nick Hornby wrote of Blood Song in The New York Times, “You can try stopping to stare at the pictures, but their strength is their simplicity . . . maybe we need lessons in how to read books like this.”

When I first met Drooker around 2010, at one of the spellbinding slideshows he puts on in the East Bay neighborhood we both call home, I tried to glean such a lesson from the artist himself. After the show I walked up to Drooker, introduced myself, and asked him to clarify an ambiguous plot point in Flood! “An author never tells,” Drooker responded coyly.

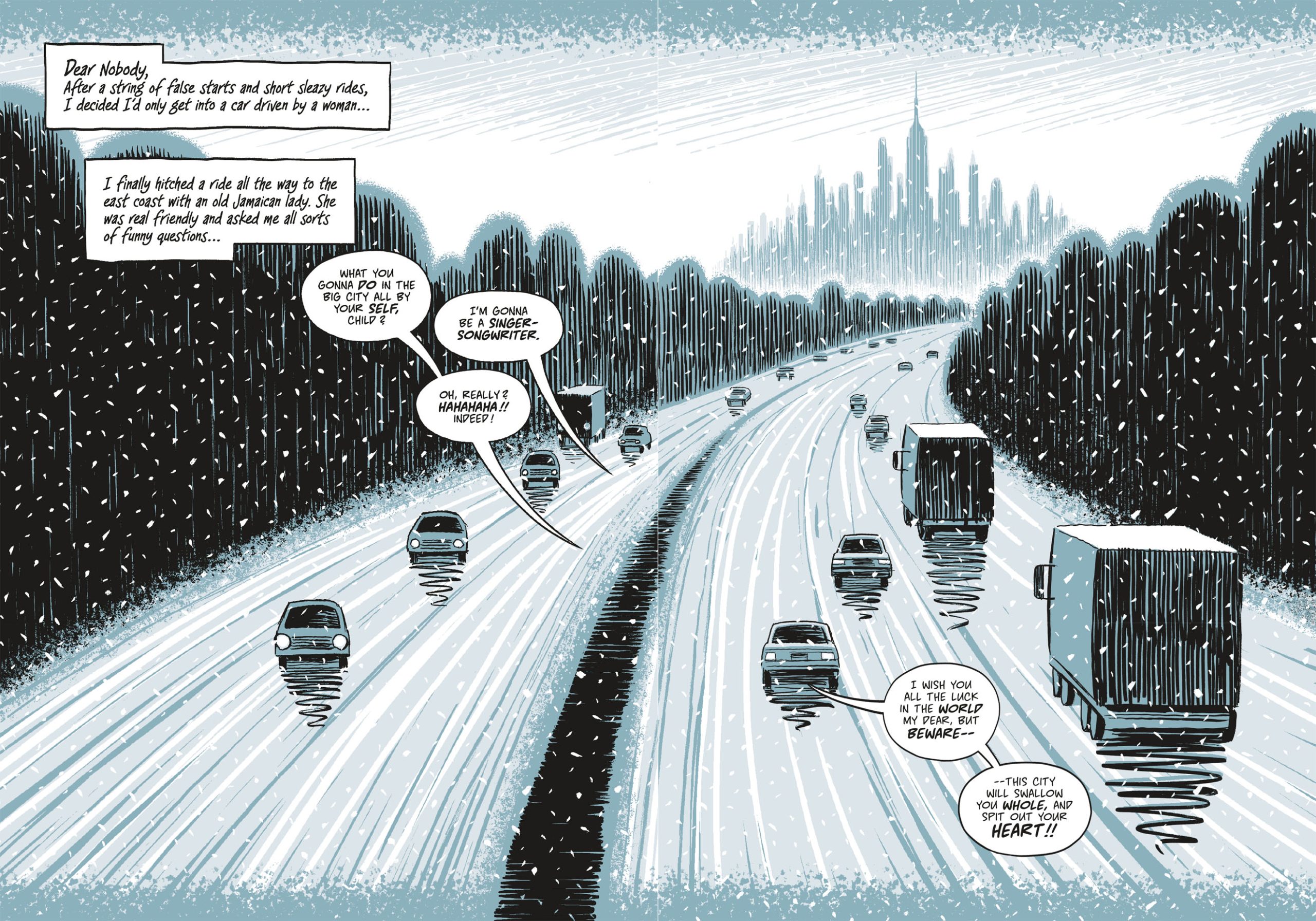

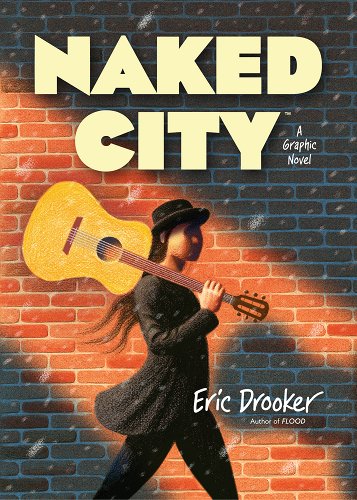

On a recent Saturday afternoon, I thought I’d try again to get a straight answer out of Drooker, this time about his latest graphic novel, Naked City, due out October 9 from Dark Horse Books. Told from the point of view of two wildly different creatives, Naked City follows a young Mexican-Italian singer-songwriter who hitchhikes to the big city searching for an audience and the genuinely-not-creepy male painter who hires her to model for his paintings. A tale of class struggle, artistic ambition, and unlikely friendship, Naked City breaks the mold of Drooker’s earlier work, incorporating dialogue throughout. In the small but airy upstairs office of his home near downtown Berkeley, Drooker was more forthcoming than before, talking about the role of the artist in an era saturated with images, the challenge of leaping into a perspective that’s not one’s own, and why the homeless window washer who calls himself Mr. Nobody is the wisest character in the book.

Carli Cutchin: The genre of the graphic novel has undergone a transformation since Flood! and even since Blood Song. My kids basically only read graphic novels, and in the adult market, there are now academic studies devoted to the genre. How does it feel to be, well, ahead of your time?

Eric Drooker: Yes, there are college curricula now studying the history of the graphic novel. In the last ten or fifteen years graphic novels have mushroomed into this legitimate art form. What makes it legitimate in our economy is that they’re selling lots of copies in bookstores. If you can find a brick and mortar bookstore, there’s a whole category for graphic novels. The art form is in a golden age.

My native tongue is pictures.

The term graphic novel wasn’t in circulation when Flood! came out thirty years ago. I would go into a bookstore and the store wouldn’t know where to put Flood! Superficially it looks like a comic book; it’s sequential art, but it’s not exactly a comic book because a comic book is this little floppy pamphlet, and Flood! was dealing with more adult things. Some bookstores would put it with science fiction; I would sometime find it in psychology. Some just put it in with the coffee table art books. Around the millennium, certainly by 2010, the graphic novel had become a category.

Graphic novels all use pictures in a sequence. Most people use the term a little wrong, they think comics are the co-mixture of words and images, but what about all the examples of comics or graphic novels that use no words, but the book is three hundred pages long? What does that have in common with Peanuts or Superman or Wonder Woman? [The graphic novel] is a sequence of images telling a story, using words or not.

CC: One of the preoccupations of Naked City is the status of images. The window washer Mr. Nobody laments to the Painter, “People prefer images over reality these days—Symbol over substance . . . But you can’t caress a symbol—You can’t eat money. Images are a dime a dozen in this town!” I thought his statement was interesting, given that your groundbreaking graphic novels Flood! and Blood Song are nothing but image, are completely wordless. In Naked City, you use dialogue to develop relationships between the characters the Painter, the singer-songwriter Izzy, and Mr. Nobody. Does your foray into words betray a loss of faith in the image?

ED: When I’m in the middle of [creating a book] a lot is unconscious and I’m going along for the ride. My native tongue is pictures. I was drawing a few years before I learned to read and write. [Naked City] gets into the nature of pictures and asks, What’s the point? Our culture is super-saturated with images already—with illusions and things like that. What’s the point of creating any new images? [Pauses.] That’s an open question.

CC: It’s always interesting when a work critiques its own medium, when it’s asking, What’s the status, what’s the purpose of what we’re doing here?

ED: What are we doing here?

CC: Right!

ED: I felt like I’d explored to the limit, How much can you tell a story without using words? Another way [Naked City] is a departure is that it’s a comedy, a dark comedy, whereas the other [novels] were so heavy. Since we’re living in such heavy times in the twenty-first century, I wanted to create some comic relief. That part was conscious. Also to have it be more cartoony. There’s enough heaviness in the world and in my life up to now.

CC: There’s this question of authenticity, too. The character of the Painter explicitly asks, Why am I creating art, what does it mean to make pictures for money? Who am I to be an artist? My question is, did you see yourself in the Painter?

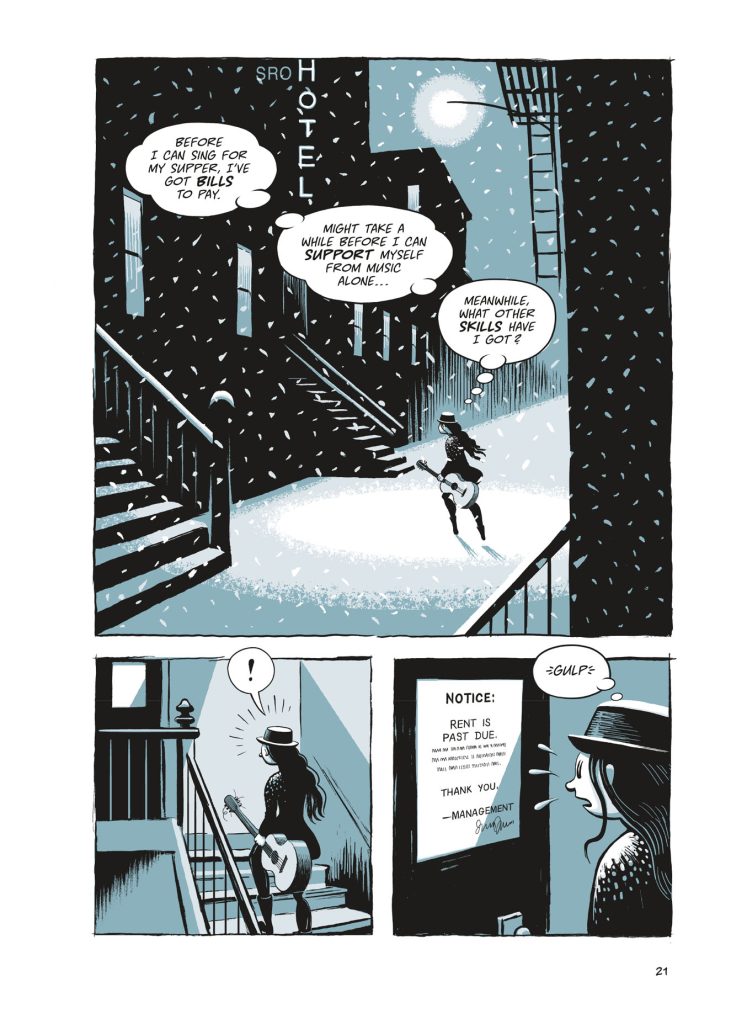

Survival is elevated to an art form in 21st-century America.

ED: It’s partly autobiographical, I suppose. The Painter resembles a younger, stupider version of myself. I am feeling a bit guilty about taking money for an artistic calling. Many artists go through this. It’s not that we’re doing it for the money. The landlord is demanding money. All the artists I know would be doing it anyway. [But] the art supplies are not free, the rent isn’t free, and the food sure the hell isn’t free. I make as much money from three New Yorker covers as for an entire book, to put it in perspective.

[Take] Mr. Nobody. He’s an artist of survival. Survival is elevated to an art form in twenty-first century America. There’s a whole permanent class of people called the homeless. Growing up in New York in the 1960s and 1970s we didn’t have [a significant] homeless population. I have a vivid memory that the word homelessness abruptly entered the language within months of Ronald Reagan becoming president. With Reagan, everything became deregulated very rapidly, including the real estate industry, which was allowed to raise prices to whatever the market would bear. Until then there were rent protections. [Suddenly] there were dozens of people walking up and down my block who didn’t have a place to stay.

CC: As you describe it, it’s as if a diaspora happened.

ED: That’s right. Before Reagan, even the poorest people lived five or ten families crammed into one tenement apartment. This concept of living on the street in a cardboard box … we’re asked to accept a permanent underclass known as the homeless, as if they’ve always been with us and they’re always going to be with us.

[But] the neoliberal era started very abruptly. Bust all the unions, deregulate all the industries, privatize everything, and offshore everything. For people who have been born and raised in [the current] era, there’s the illusion it’s always been this way.

That’s one of the things this story is about. I wanted to show the cruelty of the economic system but also how absurd and unnecessary the whole thing is, and how comic it is in its absurdity. As we get into the final chapters, a shift takes place. We realize [Mr. Nobody] is the only one who has real perspective on what the function of art is in society. Is it of any value? Who is able to make it work for them? What is the relation of art to beauty, to economics? He says the most beautiful art he heard was down in the subway. He got that from me, I noted that years ago as a young man. The most exquisite music I ever heard was down in the Lexington Avenue train station. Subway musicians are sacred to me. It’s a form of high art. When I least expected it and most needed it, I would go down and hear this incredible music, some of the best musicians in the world since they’re rehearsing for twenty hours a day. When you least expect to hear music, that’s when people need it most.

CC: There’s an interesting gender element to your work. As in Blood Song, in Naked City your primary protagonist is female, and you’re exploring issues of the female body and female empowerment. Why did you choose a young female protagonist who is—not you?

This is the gig of any storyteller, it’s a leap of faith, a leap of imagination and a leap of empathy.

ED: In Flood the protagonist was very much like—well, was the artist, you see him at the drawing board and he has a striking resemblance to yours truly. I did that early on. [Telling the story from another perspective] is more of a challenge. This is the gig of any storyteller, it’s a leap of faith, a leap of imagination and a leap of empathy. Can you tell the story through the eyes of another person who’s not like yourself?

CC: Yeah. Naked City is told from multiple perspectives, so there’s a question of, Do you want all these perspectives to be that of male Jewish artist? That could feel like navel gazing.

ED: It’s more vivid storytelling if you have a few different characters who contrast. One of the principles of aesthetics is to have vivid contrast, even if it’s abstract art. In this story, I made the decision there would be not one but two protagonists. In [my first two] stories, we’re identifying with these single journeys of these single heroes, if you will. Here, the first person we’re introduced to is Isabel, this wannabe singer-songwriter, who hitchhikes to the big city. Shortly after coming to the big city, she encounters this artist who’s a little bit older, who’s native to the city. This was a device, now that I’m looking back on it, of maximum contrast.

CC: Who are some of your favorite graphic novelists who have come on the scene in the last ten or fifteen years?

ED: I have so many favorites now. If I had to boil down which ones influenced me the most—there’s Harvey Kurtzman, the creator of Mad Magazine; before it was a magazine it was a comic book. He’s not a household name but he’s one of the most influential people in our culture. There would be no Stephen Colbert, no Weird Al Yankovic, no Saturday Night Live or The Simpsons, there might not even be a Frank Zappa without that emphasis on satire and parody that Harvey Kurzman was a master of. He in turn influenced a whole generation of underground cartoonists like R. Crumb, who’s a major influence on me, and Kim Deitch, another first-wave underground cartoonist. Right now, there’s people like Dan Clowes. Kate Beaton, a working-class woman from Canada, put out a memoir called Ducks which I think is one of the best graphic [narratives] that anyone’s done yet. Emil Farris is brilliant; she just put out of her second volume of My Favorite Thing is Monsters. Eleanor Davis wrote The Hard Tomorrow. Brilliant artwork and writing. This is a traditionally male-dominated form, comics, but the most innovative and expansive uses of the form are from women now.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.