Orlando is Virginia Woolf at play—a piece of frippery, pure queer pleasure, a little romantic, a little coy, hinting at secrets. I have returned to Orlando repeatedly over the years, most recently after a few lifetimes away. Each time, something different awaits. To return to Orlando is to travel in time. Woolf shows us how we might live multiple lifetimes in one life.

Orlando’s own time travel is doggedly linear. Orlando simply grows older, very slowly. He is 16 when we meet. I, too, am sixteen—feckless class climber, clumsy gender bender, aspiring deviant, not rich enough to be punk. It’s 1987. I have a mushroom haircut. I skulk in the basement stacks of a fancy all-girls boarding school library, poking through the Ws while cruising (without knowing I’m cruising) an aloof classmate with three last names, a buzz cut, and a “Modern Love”–era slouchy suit. Maybe her father’s, likely Armani. I fondle an ancient, good-smelling hardback of Orlando (the title of which I’ve seen on a list of “Lesbian Novels” in a book called Lesbian Lists, memorized in the corner of the New Haven women’s bookstore). I flip through a few pages, skim for dirty bits, turn up The Lion and the Cobra on my portable Radio Shack tape player, get distracted by a different classmate flipping through Artforum—her father’s a painter, she’s a photographer, and I am in thrall. I hear the voice of the father from Orlando’s mouth—gore, glory, kill, own, be a man!—the voice of empire. Orlando ventriloquizes colonial patriarchy, that bad dad, and at 16 I ignore that voice, as I do all fathers. I put the book back on the shelf, and for decades will remember that I first read Orlando at sixteen.

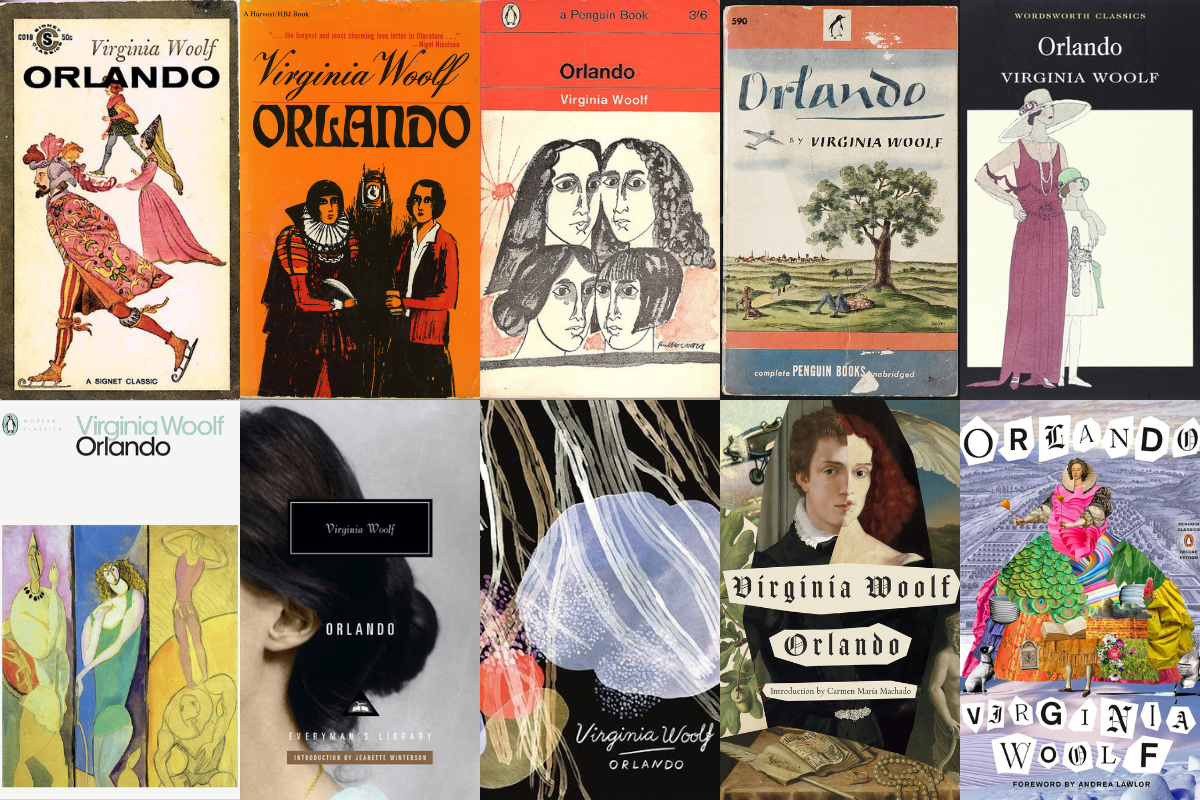

It’s 1990; I’m 19. I’m carrying my unread Signet Classics Orlando around a Jesuit college to impress my Novels of Transgression professor, who is a Modernist, which I’ve just learned means queer, which I’ve begun to understand is cooler than lesbian, or maybe just more accurate for me personally, which I won’t understand fully for ten more years (at least). I’m also carrying around a copy of Violet to Vita, a collection of love letters between Woolf’s beloved Vita Sackville-West (the inspiration for Orlando) and Vita’s other lover, the writer Violet Trefusis (the inspiration for Sasha). I try briefly to be femme to secure the attentions of a funny, handsome, and extremely authoritative butch writer whom, I will soon realize, I’m actually trying to be, not do. I’m impressed by Woolf’s dedication to seduction, the commitment it takes to write a whole book as a romantic gesture.

I have returned to Orlando repeatedly over the years, most recently after a few lifetimes away. Each time, something different awaits.

Two years later, I’m annotating my now-thrashed copy of Orlando, which I’m actually reading, to impress a different queer Modernist professor at a big state university. My comments are a master class in jejune opinions and point scoring, presented in careful, art-boy block lettering. Confronted with racist language and imagery, I angrily print coloNialism! Titillated by Woolf’s gender theory, I abbreviate scandalous terms, thrilling at my own esoteric knowledge, my range. I revel in Woolf’s light approach to gender, how Orlando becomes a woman who cross-dresses and finds adventure in the demimonde, the bits of earnest queer romance that slip through.

I have an ancestor, finally.

In class, I read Orlando in contrast to another formative queer novel, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, also published in 1928 and following the depressing life and melodramatic death of a wealthy British invert, Stephen Gordon. I prefer my playful ancestor, the one who wanders between genders, lives centuries without a scratch. And yet, I bore easily. I’m annoyed by Woolf’s satiric treatment of the literary world. I tire of her obsession with time. I want more dirty parts. I take some ill-gotten Ritalin and slow down enough to appreciate the ellipses, but I turn to Mrs. Dalloway for something more palatable—these gestures toward sapphic sincerity, toward rapture. Something less compromised.

It’s hard to get past the first paragraph of Orlando. In fact, you can’t actually “get past” the first line of Orlando, and neither can I. Whatever Woolf intends (a misguided attempt at a feminist critique of colonial masculinity is the most generous reading), her exalted prose style can’t help but exult in the pageant of the teenaged white boy Orlando desecrating the body of a dead African man:

“He—for there could be no doubt of his sex, though the fashion of the time did something to disguise it—was in the act of slicing at the head of a Moor which swung from the rafters.”

Orlando is a book from another time, and no amount of historical context will change how it is compromised by Woolf’s Orientalist preoccupation with racialized bodies, her zeal in evoking Blackness in racist terms. We don’t get past the racism that rises from these pages, that haunts this book and many others of its time. We don’t read the book in spite of it, either. If we keep reading, we read into the time, understanding that whiteness and all its violence, along with Woolf’s brilliance, her vision, her profound intimacy with the English language, are among the forces that shape this literature.

It’s 1993. I’m alone in the dark of the campus movie theater, discovering Tilda Swinton in Sally Potter’s Orlando. I’m undone by cinema, where everything happens with no explanation. I’m transfixed by the film’s opening, the knowing glance, the relief of Potter’s elision of Woolf’s first paragraph, the sinister elegance of that pivot, which I call feminist. I’m entirely seduced by Jimmy Somerville’s sexy Anglican countertenor, by Quentin Crisp’s powdered queen, by the offer of inclusion in the gay-boys’ club, by Woolf’s queer window on history showing all of European time as gay, gay, gay, and by Swinton’s performance suggesting that female masculinity could be cool like Derek Jarman was cool.

We read into the time, understanding that whiteness and all its violence, along with Woolf’s brilliance, are among the forces that shape this literature.

Potter’s Orlando is aristocratic queer feminist camp. This is a balm. I imagine Potter must have identified with Orlando; maybe Tilda Swinton did, too. To be a woman director or lead actor in 1993 was to fight on a battlefield where Woolf had fought only decades before, and casting Swinton helps us to see Orlando as the story of a woman artist. Potter’s Orlando also tells a story about aging queerly, and at the time, it offered an out—gender-fluid immortality—to those of us whose people were dying. (Charlotte Valandrey, who plays Sasha, died in 2022, with HIV. She was 53.) Potter mostly avoids Woolf’s race problems, prefers to play with the middle of the first line: “. . . there could be no doubt of his sex, though the fashion of the time did something to disguise it.” That’s a choice, I see now.

What Orlando aficionado hasn’t tried an adaptation? An explosion of takes marks this new century, includes playwrights, fashion designers, graphic novelists, curators, drag kings, librettists. Perhaps most significantly, Paul B. Preciado’s 2023 documentary, Orlando, My Political Biography, challenges Woolf’s colonialism and racism from a trans perspective and makes manifest Orlando’s multitudes by casting twenty racially diverse trans and nonbinary people (alongside Preciado himself) to play the lead.

It’s 1994. For Halloween I’m Potter’s Sasha, Orlando’s love. With my dark curls, who else could I be? Plus I have the right hat, a faux fur thrift score. I feel myself to be in drag but am unable to communicate this to others. I flirt with a long-haired bisexual boy or maybe my straight girl roommate or maybe both.

Then there’s some years between 1994 and 2007, when I remember only one thing about Orlando—the passage where Orlando goes to sleep, sleeps for a long time, and wakes up as a girl. The ease. Class magic, Woolf’s inheritance of audacity.

In 2007, a writer I know, Tisa Bryant, publishes a collection of essays, including one on Orlando called “The Head of the Moor.” Bryant writes:

“Woolf apparently believed that a human being is made up of thousands of selves existing across time and space. Woolf writ- ing as parodist, lover, critic, self, and more. But there’s much in Orlando’s fabric that . . . deep knowledge of [Woolf] . . . cannot account for, the racialized darkness throughout, exoticized, yes, but not interrogated, over time and space, between thousands of selves, writer, critic, reader, admirer, gatekeeper.”

I see that I have been reading through my whiteness, yet again.

This new edition is an opportunity to revisit Orlando. We are friends across time, me and this unruly queer ancestor of ours.

Fast-forward to 2019. I’ve written a novel some people have compared to Orlando, which I accept as a kindness. I see what they mean, of course, what with the shapeshifting, the refusal to explain, the attention to the fashion of the times. And Orlando really must have been somewhere in my mind as I wrote—for, like its hero, I took 342 years to finish my first book. I’ve been flown to England and on my first day ever in the country, I’m rambling jetlagged around Charleston House with my publicist, marveling at this pilgrimage she set up, to the Bloomsbury Group’s HQ, that bisexual idyll where writers wrote and painters painted and everyone slept with everyone else, a pocket of freedom in a war-stunned country, or so the story goes. Later at Monk’s House, in Woolf’s small writing lodge, I marvel again: she wrote her dazzling sentences here, those radiant paragraphs. Was this the very desk where she wrote the “Time Passes” section of To the Lighthouse? Did she walk the garden path, dreaming of Sally and Clarissa in their youth? Did she gaze out this window, imagining Vita as the ambassador to Constantinople, imagining revolutions, imagining that one might change one’s body and find some new liberation? My publicist and I take selfies, which I post to Instagram, interpolating myself into this literary lineage. I haven’t shaved in a week and have a small asymmetrical collection of hairs above my lip, which I hope creates some hormonal ambiguity on this book tour where, as usual, I don’t feel trans enough and also feel too butch, which in 2019 feels as archaic as heterosexuality.

I stoop through the old doorways, gender-affirmed but an interloper in an aristocrat’s rustic fantasy.

Now it’s 2023. I’ve been asked to introduce Orlando, and I accept, thinking of the opportunity to say something about reading differently with time and experience, about reading as a white person, about how it’s good to change over time—and also thinking about the prestige, linking my name with Woolf’s. Late Western capitalism flows through me.

I felt one way at first, I feel differently now, I will likely feel a new way in the future… Reading, like life, is subject to revision.

I am asked to write something personal, which at first I resist. Like that other queer refusenik Bartleby, I would prefer not to. I have changed since I first encountered Orlando 35 years ago—what adult hasn’t changed in 35 years? And because I have changed, how I read has changed. I’ve even changed since I first started writing this essay, in the summer of 2023. I’m recovering from recent top surgery, once a topic for a memoir and now routine, covered by insurance. I am rereading Orlando—arguably the first modern transition narrative—during my recovery. Like Orlando, I find that I have woken up over a crack in the sidewalk, feeling not much different in my new body. Instead of thinking about gender, I find to my surprise that what resonates now is Orlando as Künstlerroman, the maturing of the artist. What resonates now are all Woolf’s ideas about metaphor, her finely crafted arguments about the material conditions necessary to write, even the bits about marriage. What did I learn from Orlando? I learned that we could play with gender, not take everything so seriously all the time, oh my god. I learned that transformation could be the easy thing, writing the hard thing. I learned that writers could skewer other writers’ ambitions, and I learned to fear being skewered thusly. I learned that rich people really care about their inheritances. I learned that white people often need to read a few times to see what’s on the page. I recently learned that Woolf was writing climate fiction a hundred years ago. Every time, a surprise. What do I take with me? The queer art of refusal, with a soupçon of aristocratic entitlement mixed in. Also, that one might write a book to impress girls.

This last time I meet Orlando, I’m 52. On the last page, Orlando is 36. And Woolf is 46, in 1928, at the time of publication. Impossibly, they are both younger than I am now. I’m old enough to have seen more than a few decades of literary life unfold, to have reread my early influences and revised my thinking, to have been revised myself by reading. To have revised my own body while time revises me. This new edition is an opportunity to revisit Orlando, as artists have done for a century. We are friends across time, me and this unruly queer ancestor of ours.

Rereading this book that has accompanied me throughout most of my life, I am left with this: I felt one way at first, I feel differently now, I will likely feel a new way in the future. Like Woolf, I will resist explanation and merely say that reading, like life, is subject to revision.

My own centuries, both of them, are the ruins of Orlando’s times. And yet we all live here. There’s no place outside the ruins, no place to return. We root around in the remainders, hold up the shards to the light of history, the light of transformation, the light of time. Woolf as ancestor, in this stream of time. What can she tell us? What can we tell her?

From Orlando by Virginia Wolf, published by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Foreword copyright © 2024 by Andrea Lawlor.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.