The twelfth-century Cistercian monastery of Poblet has endured its share of hardship over the years as wave after wave of warring groups plundered their way through the vineyards and olive groves. Poblet has left its history of setbacks behind to develop into a monastery that boasts one of the most cutting-edge monastic gardening programs in the world. What the investment banker turned monk from Barcelona in charge of the vast gardens, orchards, and vineyards doesn’t send to the monastery’s kitchen or culinary training program for disenfranchised youth, he pickles or dehydrates for the Tarragonian winter.

Article continues after advertisement

The monastery, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is a two-hour drive from Barcelona, on the southern border of Catalonia. Poblet is one of the largest and most complete Cistercian monasteries in the world. It towers above the valley as an imposing reminder of nearly nine hundred years of Spanish history, in all its illuminated triumphs and grievous defeats.

The abbey of the monastery rises up from the russet foothills of the Prades Mountains. Inside the abbey, alabaster statues of Christian icons watch over the ancient tombs of kings and queens who ruled for centuries over the legendary Kingdom of Aragon. Fra Borja Peyra, a former investment banker in his early forties with salt-and-pepper hair and a relaxed nature, details the conflicts the monastery has endured throughout its existence. It was closed altogether in 1835, when an edict from Prime Minister Juan Álvarez Mendizábal to confiscate all Church properties ushered in a dark time for the monasteries of Spain. Poblet was not spared. Pillaging transformed the grand complex, with its six-foot-thick battlement walls and intricately carved porticos, to ruins. Fortunately, many of Poblet’s most valuable paintings, treasures, and furniture were safeguarded in private homes in the surrounding villages before a catastrophic fire ravaged what was left of the monastery.

Over a century later, Italian monks of the same Cistercian order reopened Poblet’s doors after a painstaking restoration process initiated in 1940 to return the monastery to its original splendor.

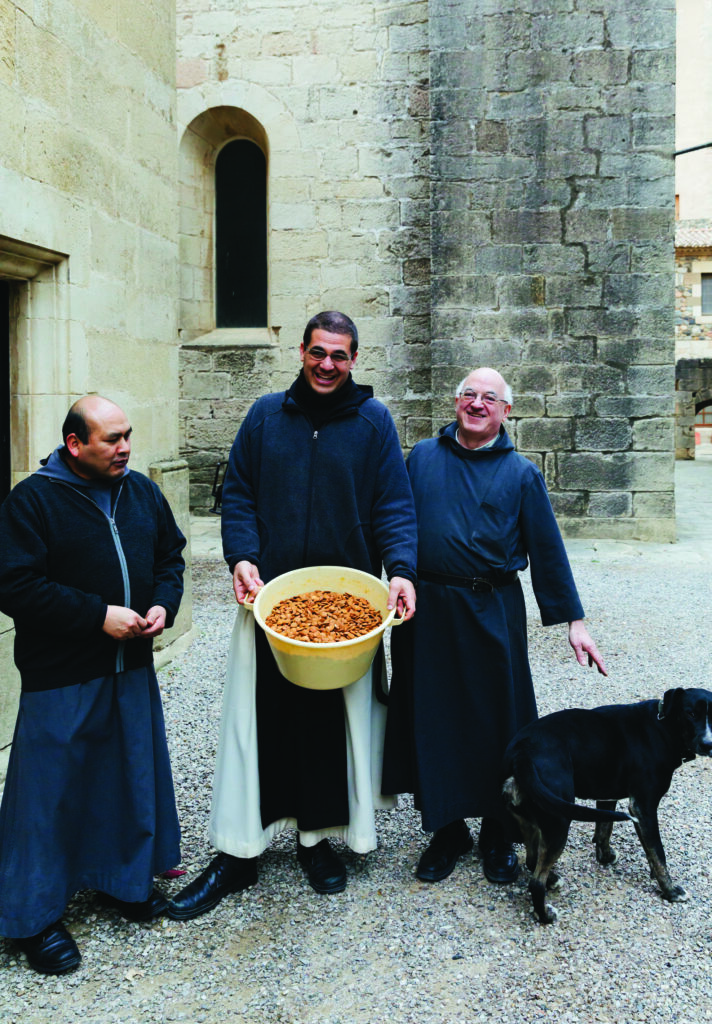

Fra Borja smiles with a finger to his lips as he strolls along a cobblestone lane past lemon and hazelnut trees on this sunny but cool autumn morning. We stop to feed his chickens before ducking into the vast pantry to inspect the freshly harvested crates of persimmons and baskets heaped with almonds. Along the edge of the property, Fra Borja finds his stride in a garden that tumbles down the hillside to the olive and almond groves far below.

He proudly explains that he is the monk in charge of the gardening program at Poblet, where they employ an amalgamation of ancient wisdom and modern technology to coax everything from tomatoes to beans to carrots from the region’s fertile soil. Their goal is to be completely self-sustaining, with any excess distributed to the surrounding villages as a way to ensure that the time-tested kinship between the monks of Poblet and the people of Catalonia endures.

There is no sorrow in his voice as he discusses what had been vanquished, only optimism and possibility.

One of the things I’m working on that excites me most is a hydroponic growing system that I am installing in one of the greenhouses before winter sets in. If it’s a success, we will be able to complement the preserved fruits and vegetables we serve during the winter months with fresh produce. It’s a challenge for me because there are only a few younger monks now living at Poblet who can handle manual labor. I must balance my heavy workload with the care of the elderly monks who rely upon us. But this is what living in a monastic community is all about. It reflects society as a whole; to survive and to thrive, you must look out for one another.

There is no sorrow in his voice as he discusses what had been vanquished, only optimism and possibility.

Fra Borja steps into an imposing stone room housing nothing but an intricate wooden rack upon which thousands of plump, ripe tomatoes are hung. He breaks one off the vine and bites into its taut red flesh, juice as vibrant as a tomato picked in the heart of summer dripping down his chin and fingers. He wipes his chin with the sleeve of his fawn-colored habit. “In Catalonia, this is a traditional way to preserve our tomatoes. Hanging them in this manner enables them to ripen to a sweet finish without spoiling. If we are fortunate, they will last us all winter long,” he says as he runs his fingers through buckets of dried pinto beans and almonds.

He lifts up a sheet of burlap to reveal large glass jars of pickled vegetables prepared for the ensuing winter months and points to hundreds of fingerling potatoes and yellow onions carefully arranged on the cleanly swept stone floor. He says, “The cold floor preserves them long enough to carry us through the season. You don’t need a root cellar, just a place brisk and dark enough to keep them in the game.”

We walk to the refectory, where around thirty-five monks gather for their meals each day. A ray of sun beams down upon the long wooden tables, where settings of balsamic vinegar, olive oil, red and white wine, water, salt, and bread are carefully arranged for each monk. Poblet is renowned for its wine, especially its Pinot Noir, a tradition nearly as ancient as the monastery’s eight hundred years.

Fra Borja explains that the handcrafted pottery in shades of chestnut, burgundy, and ecru was made by one of the monks. “Each one of us is encouraged to create something of value to be used at the monastery or sold in the gift shop to support the ethos of self-reliance that we encourage here.” He picks up a ceramic wine goblet and inspects it before whispering, “I’m not sure if we are earning a profit from this monk’s work, however. He breaks most of the pottery before he finishes firing it.”

The resident chef of Poblet, Felip Abela, a silver-haired monk in his fifties, begins the lunch preparations in the next room. After a mushroom-foraging session and a trip to the herb garden just outside the basement kitchen’s door to snip parsley, thyme, and sorrel for the meal, he begins to cook. There is a massive paella pan in one corner of the room tended by Felix and Sergi, two young men who look nothing at all like monks. The one wearing a backward baseball cap pours enough olive oil to coat the bottom of the pan and concocts a deep red sofrito of tomatoes, onions, garlic, and spices before his cooking partner, who sports a Barcelona football jersey, sifts in large spoonfuls of bomba rice. The rice hisses, filling the room with a toasty aroma coupled with the potent, nose-tickling scent of the sofrito.

Fra Borja whispers that the young men are not residents of Poblet but troubled youth who are trained at the monastery to be cooks. The investment arms them with a skill the monks hope will transform their lives. The novice chefs share a few jokes in Spanish with their mentor, who has opened a jar of preserved pears that he slices thinly and arranges on a dehydrating tray, to be served with whipped goat cheese and fig syrup for dessert.

After a few hours of prepping and cooking, the monks file into the rectory for their meal. They are a noisy bunch, ribbing each other as they sip Poblet wine. Fra Borja sits next to a young monk who he explains will be assisting him with his hydroponic project. “We have big plans for the future,” Fra Borja says before digging his fork into his plateful of paella. He sinks his teeth into a creamy roasted potato slicked with olive oil, then pops a slice of rack-dried tomato in his mouth. He closes his eyes and grins. “A Catalonian summer right here in my mouth on a cool autumn day. Life is good, in spite of my sacrifice.”

“But this is what living in a monastic community is all about. It reflects society as a whole; to survive and to thrive, you must look out for one another.”

*

Shrimp and Chorizo Paella

Serves: 6

Preparation time: 2 hours

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

8 ounces chorizo, cut into 1/2-inch pieces

2 medium white onions, coarsely chopped

4 garlic cloves, finely chopped

1 (16-ounce) can crushed tomatoes

2 medium tomatoes, coarsely chopped

2 roasted piquillo peppers (see page 73), coarsely chopped

1/2 cup chopped fresh flat-leaf parsley, coarsely chopped, plus more for garnish

1 bay leaf

1 tablespoon smoked paprika

1 teaspoon Spanish saffron threads (see page 73), crumbled

1 cup bomba rice

1 cup dry white wine

6 cups fish stock

1 teaspoon salt

1 pound large shrimp, peeled (heads and tails left on, if desired) and deveined

Lemon wedges, for serving

Crusty bread, for serving

Every country claims a national dish, and for Spain it is paella. It graces tables from north to south and east to west, each incarnation reflecting the natural resources and gastronomic customs of the region. There are several steps involved in creating this paella, but they are not complicated. With a little patience, you will discover paella’s irresistible character, as the Spanish have done for centuries. At the beginning of the cooking process, the foundational ingredients—onions, garlic, tomatoes, and spices—are combined. Give these elements time to commune and chat it up a bit until they form a thick paste called a sofrito. This is your flavor bomb and with it, you’re well on your way to a paella championship.

The crusty layer of rice that forms on the bottom of the pan during the final stage of the cooking process is called the socarrat. It’s discussed in this recipe’s notes and is another crucial factor for a sublime paella. Although a paella pan is not necessary, a wide, shallow pan is preferred because it will allow a generous socarrat to form and also enable more balanced cooking. The flame should also be evenly distributed beneath the pan, which of course means that the ideal environment is a wood-burning fire, but in case you don’t find yourself living in the ultimate paella fantasy world, use two stovetop burners beneath the pan as opposed to one.

This recipe calls for spicy Spanish chorizo and shrimp, but of course, any protein combination will suffice. Note that Spanish chorizo is a cured sausage, not to be confused with raw Mexican chorizo. Chicken, lobster, fish, and mussels are excellent backup plans. Chicken or vegetable stock (or even water in a pinch) are good swaps for the fish stock. If you keep all this in mind, you’ll be well on your way to a lustrous paella—just channel the resident chef at Poblet, who advises, “Let paella wander around a bit, find its footing, develop a solid foundation all on its own. It knows what it’s doing. It’s been doing it in Spain since the beginning of time, or at least since good food became a part of what time is all about.”

Preheat the oven to 375°f.

In a paella pan or a large, shallow ovenproof skillet, heat the oil over medium heat. Add the chorizo and sauté until crispy and golden brown, 7 to 9 minutes. Transfer to a paper towel–lined plate and set aside.

Add the onions to the fat left in the pan and sauté until tender and caramelized, about 7 minutes. Add the garlic and sauté until tender and aromatic, about 2 minutes. Add the crushed and fresh tomatoes and piquillo peppers and bring to a low simmer, then add the parsley, bay leaf, smoked paprika, and saffron. Simmer until the sofrito is thick and caramelized, about 7 minutes. Add the rice and cook for 2 minutes while stirring continuously, then add the wine and 3 cups stock and bring to a boil.

Season with the salt, reduce the heat to medium-low, and cook at a gentle simmer until the rice has absorbed nearly all of the liquid, about 20 minutes. Stir occasionally to prevent burning. Increase the heat to medium, stir in the reserved chorizo and remaining 3 cups stock, and bring to a simmer. Cook until the rice has absorbed nearly all of the liquid, about 10 minutes. Remove the bay leaf.

Add the shrimp, burying them as deep into the rice as you can, and transfer the pan to the oven. Bake for 20 minutes, or until the shrimp are bright pink and cooked through and the socarrat is crispy and dark caramel-red. Lightly cover the pan with aluminum foil and let rest at room temperature for 10 minutes. Garnish with parsley and serve from the paella pan for dramatic effect, alongside a bowl of lemon wedges and hunks of crusty bread. Leftovers will keep in a covered container in the refrigerator for up to 5 days.

Key Paella Ingredients and Tools

The first, and many would agree, most crucial element for a successful paella is the rice. The Spanish use a short, fat rice called BOMBA, which is similar to arborio should you not be able to locate bomba at your market. Long-grain rice will not do because the grain needs to be plump and ready to soak up all the flavor.

Piquillo peppers are a specialty of northern Spain, where their name translates as “little beaks.” These diminutive red jewels are prized for their sweetness and the depth of flavor they command when roasted. Piquillos are typically roasted, seeded, and sold in jars of brine. They are available in many grocery stores and specialty Spanish markets, but should you have trouble sourcing them, roasted red bell peppers make a good substitute.

Saffron is prized throughout the world for its unique flavor, the color it adds to a dish, and the backbreaking work required to harvest it. Saffron is the stamen of the crocus plant, and each purple flower produces only three precious threads of saffron, making the time and labor required to procure it highly intensive. Spanish saffron is not as prized as Iranian or Kashmiri saffron, but don’t tell that to a Spaniard—they covet their saffron as much as they do their wine and siestas. Of course, nothing matches the flavor of authentic Spanish saffron, but in a pinch, 2 teaspoons ground turmeric will lend a similar color to this paella recipe.

One of the most crucial reasons to use a paella pan as opposed to a pan that is not as shallow and wide is for the socarrat, the irresistible layer of rice that caramelizes on the bottom of the pan during the final stage of cooking. This crusty flavor explosion is the thing that every paella lover will inspect (and wage war for) when the pan is set down in front of them. Give your paella time to develop its socarrat by letting the magic happen in the oven as long as it needs to.

__________________________________

From Elysian Kitchens: Recipes Inspired by the Traditions and Tastes of the World’s Sacred Spaces by Jody Eddy. Copyright © 2024. Available from W.W. Norton & Company.