I am not a creature of luxury, so it might seem strange that my novel is full of it.

Article continues after advertisement

The luxury was by accident. As someone who had for, a very long time, been on tour for my YA books one day out of every three, I had already decided I wanted my next novel to live in the liminal space of a hotel. And as a history major, I’d already decided I wanted my first novel for adults to live in the past. The early stages of novel-writing are opportunistic wool-gathering, so I can’t tell you where I first read a single, throwaway line describing the time the State Department had tapped a handful of rural hotels, including several in Virginia and West Virginia, to house hundreds of Axis diplomats until they could be repatriated, but I can tell you my first thought: those are my mountains.

I was born in the Shenandoah Valley, within easy driving distance of both the Greenbrier and the Homestead Hotel, two of the real-life hotels. How had I never heard about this?

It was an irresistible set up. A succinct, metaphorical backdrop on which to play out the story of a woman trying to untangle her future from her past, all contained inside my complicated and beloved home territory.

The moment it looks like work, luxury vanishes, replaced by its uglier, more mundane cousin: wealth.

The rub, of course, was luxury.

Guests of the Greenbrier alone included Woodrow Wilson, JFK, Nixon, Reagan, not one Bush but two; add Taft, Eisenhower, and Coolidge, and you’ve got the guest list of the Grove Park Inn. The real-life hotels of the diplomatic detentions were not just luxurious. They were exemplars of luxury.

This was an unfamiliar world.

I met with the Greenbrier’s historian; I spoke with the Bath County archives. I read the hotel memoirs of Ludwig Bemelman, Frank Case, and Conrad Hilton. I dug into the only book written on the detentions and then, when it came out midway through my own writing process, the second. Historians offered me unpublished memoirs from Swiss citizens pressed into service as neutral parties and out-of-print memoirs from children who had been part of the detention. From these, I absorbed the reality of these hotels. Black tie dining rooms and themed balls. Fur coats for guests who hadn’t anticipated a cold snap. Horses in the stables; orchestras above the swimming pools; electric cabinets humming in sweet-smelling bathhouses. Game nights in massive libraries; debutante balls swirling around marble fountains. The stuff of princess fantasies.

As part of my research for the novel, I spoke to a Swiss hotelier with a management resume featuring hotels all over the world, including a European property that went for $54,000 a night.

“How do you spoil the rich?” he mused. “They can buy anything you might give them. When they spend two million during their stay, but hug you for the privilege of spending it,” he added, “that’s when you know you’ve succeeded.”

“What do these people do?” I asked.

“You don’t want to know.”

But what he meant was it doesn’t matter.

*

About seven years ago, long before The Listeners was on my mind, I found myself at a Jackson Hole luxury resort, not as a novelist, but as an automotive journalist, test-driving the latest Rolls-Royce on behalf of Road & Track. (The truth is that I really like cars, had a midlife crisis, and let myself be wooed by multiple automotive magazines into writing features for several years.) Rolls-Royce, who was putting the journalists up, had arranged for accommodations to be commensurate with their product. The resort had spa services, heated floors, the most expensive hair dryer I’d ever seen, and free internet, which I used to pay a speeding ticket.

What a lot of noise, I thought, as I ate peanut butter from the jar I’d brought with me. I wasn’t here for filet mignon and hot rocks, I was here for the machines.

A card on my pillow asked me to call the front desk if I wanted absolutely anything.

Easiest phone call I never made.

Unknowingly, I was conflating luxury and wealth.

*

In pursuit of understanding, I spoke to a professor at the Cornell School of Hospitality. “Guests are a multiplier of the hospitality,” he told me; dutifully, I wrote it down and underlined it.

He spoke of luxury as a game, one where not all players were created equal—on either side of the board. Quality staff members enjoyed the challenge of pleasing their charges. Quality guests recognized the game as something more than mere service. The giver did not resent the recipient; the recipient respected the giver. It sounded mannered and artificial, like 18th century warfare. They lined up on Tuesday mornings to point pistols at one another and took holidays off.

“…refined, not crass.”

He was still talking about the ideal guest. It took me awhile to understand what he was trying to say. A bad guest wasn’t an entitled one. It was one who didn’t recognize the worth of what the hotel was trying to do.

He was talking about me.

In a world where individual identities are being stripped away by a thousand frightening factors, the luxury of being known is more important, not less.

I read about Ralph Hitz, one of the great hoteliers of the early 20th century. Like many great hoteliers, he began as a mere bellboy and worked his way up. This, most agree, is the only way to understand the magic. Front and back of house must dance seamlessly to make luxury seem almost playful. The moment it looks like work, luxury vanishes, replaced by its uglier, more mundane cousin: wealth. The rich can get that back home.

By the 1930s, Hitz was not just a manager—he was a pioneer of the industry. One of his innovations was the practice of keeping extensive records of his returning guests’ preferences. Stanley Turkel, his biographer, relates: “During the registration procedure the word loved most by the guest, his name, was used at least three times…This ‘strange music’ of one’s name did not stop until the guest was cozily settled in his room.”

“The rich can buy champagne,” my Swiss hotelier concurred, nearly one hundred years later. “They can’t buy being known.”

Knowing their names, of course, is a metaphor. He, like Hitz, took note of their favorite drinks, their anniversaries, if they always moved their nightstand closer to the bed. The staff then made this and much more happen—unasked, because here is another way luxury differs from wealth. Wealth does what you tell it to. Luxury surprises you.

*

At the Jackson Hole resort, when I joined the crowd in the dining room, the Rolls-Royce team waved me away from the journalist tables and pulled out a chair at theirs. They asked, Was I the novelist? The one who drove the Mitsubishi Evo? Maggie?

I was shocked at being known in a setting that didn’t demand it. Suddenly, I was not one of many, but rather, an individual. The gesture was effortless, personal, memorable, and surprising. It cost nothing.

This was luxury.

I forgive myself for misunderstanding, because luxury has become so entangled with indulgence. Most hotels, even the starry ones, traffic in just a newsletter mimic of the real stuff. But in a world where individual identities are being stripped away by a thousand frightening factors, the luxury of being known is more important, not less. It has nothing to do with wealth. The only cost is agreeing to play the game.

I’m in.

__________________________________

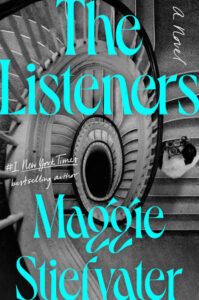

The Listeners by Maggie Stiefvater is available from Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.