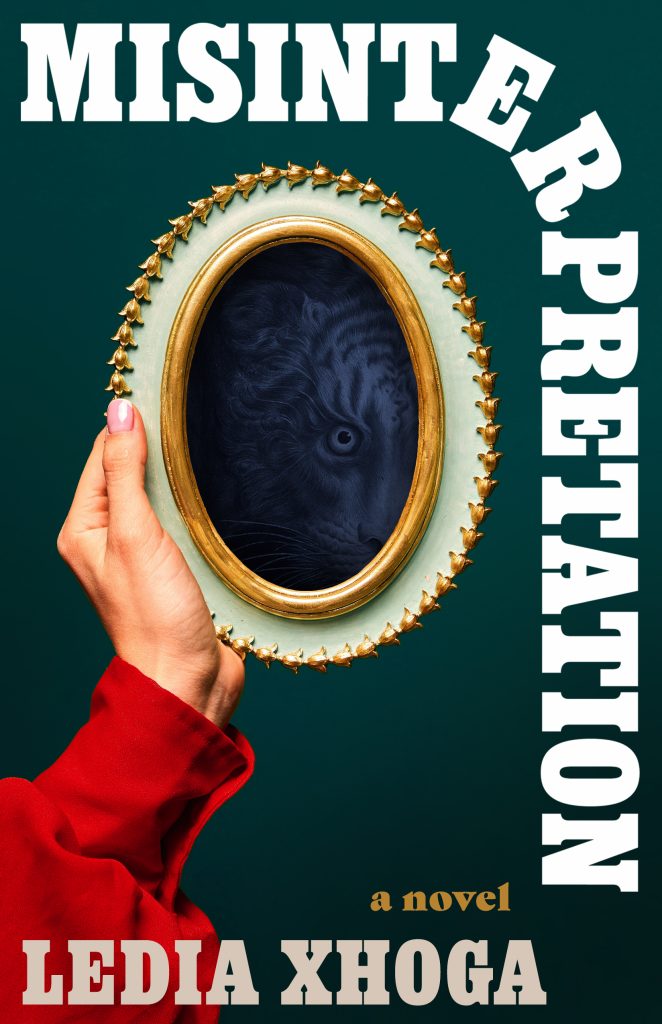

Ledia Xhoga’s debut novel Misinterpretation opens with the unnamed narrator, a translator from Albania, accepting an assignment to interpret for a Kosovar torture survivor named Alfred. Elements of Alfred’s story map onto her own family’s experience, and the narrator becomes all-consumed by his case. As personal and professional boundaries start to blur, the narrator is caught up in the precarious lives of other asylum seekers, like Leyla, a Kurdish poet who is being stalked by her ex-husband. Eventually, the narrator has to face the consequences of her meddling and the toll it takes on her professional life, her marriage, and even the lives of the people she’s trying to help.

The narrator reflects at one point, “Since moving to America, my life had been like… two parallel highways with regular exits onto each other.” In Misinterpretation, Xhoga artfully captures the experience of having a foot in two different worlds and how the narrator’s reality is distorted as a result of constantly shifting between them. Being able to speak so many languages and translate for so many different people gives the narrator a deep capacity for empathy, but it also complicates her relationships, blurs the lines between her identity and the people she translates for, and raises ethical questions about friendship and boundaries.

As an immigration journalist, translator, and nonprofit director providing services to asylum seekers, I was impressed by how deftly Xhoga captures the challenges of translation and the complexities of navigating the US immigration system. I spoke to Xhoga ahead of the novel’s release to discuss what it’s like to live on the border between two worlds, the unseen struggles of asylum-seekers, and how language shapes our world view.

Shoshana Akabas: The story starts with the narrator interpreting for a Kosovar torture survivor, despite her training that “if the interpreter’s circumstances resemble the client’s, do not accept the assignment.” What drives her to accept the job anyway?

Ledia Xhoga: For me, writing the book started with a “what if?” At one point, I volunteered to interpret for an organization that helps survivors of torture. I was supposed to interpret for someone, but it didn’t work out, and I always wondered what could have happened. So, that was the initial spark.

What convinced me that there was a novel in it—because, you know, there could have been nothing, it could have been a short story—but what convinced me was the complexity of the main character. She is very committed to helping other people, but eventually her behavior becomes disconcerting, because she’s incapable of holding two opposing viewpoints inside of her. And the novel starts from that moment when she realizes that maybe this is not such a good idea, because Alfred’s situation is bringing up a lot of her own past traumas. But on the other hand, she can’t help it. She has this compulsion to help other people that’s unchecked, at times, by other considerations.

SA: That’s very different from how her American husband moves through the world. He sees very clear limitations and boundaries. What do you think accounts for that difference?

LX: I think some of it is probably upbringing or cultural. I’ve noticed in my life that my husband and I are very different, and with American friends, sometimes I notice that they see things differently and boundaries are different in other cultures.

SA: Like when the narrator visits Albania, everyone knows each others’ business, whereas when she’s in the United States, lots of characters keep secrets from each other.

LX: Exactly. In Albania, for example, it’s very common for people to live together. Even if you are married and have kids, you can still live with your parents. They live in such close proximity to you. That doesn’t happen as much in the United States. The idea of boundaries is much more pronounced in American culture.

SA: I also wonder how the narrator’s translation work shapes her worldview. As a translator, she’s used to slipping into different lives and sort of embodying the person she’s interpreting for.

LX: You have to be very flexible when you’re translating. It’s not as simple as, “I’m going to tell you this exact sentence.” It’s more like, “I’m going to say it in a way that you’ll understand.” Instead of being analytical, you’re trusting your intuition, your emotions, and understanding the other person’s body language. You’re so much more involved, immersed in the experience.

SA: Let’s talk about the title for a minute. Translation figures into the story in so many different ways. How does the theme of mistranslation run through this book?

LX: So many ways. In everyday communication, even within the same language, even with your family members, there can be two opposing views. You can look at the same thing in different ways. Misinterpretation is everywhere. And of course, it takes on another meaning when you bring in a different language. It’s especially pertinent to the story, because during the therapy sessions, she really misinterprets Alfred, and she withdraws so much into her own trauma, into her own past. So I started to think of ‘Misinterpretation’ as the title after I wrote the scene with Alfred when there was a real misinterpretation. But the more I continue to write, the more I could see other things being misinterpreted throughout the book. And then, there’s this wider meaning that a work of art is always going to mean something different to different people. Any work of art, anything that you create, will necessarily be, in a way, misinterpreted.

SA: The theme of translation in this book is so beautifully complemented by the theme of immigration and the idea of having a foot in two different worlds. Can you talk a bit about how these two themes work hand-in-hand for you?

In everyday communication, even within the same language, even with your family members, there can be two opposing views.

LX: I read this quote by Toni Morrison, “I stood at the border, stood at the edge and claimed it as central. I claimed it as central, and let the rest of the world move over to where I was.” It totally spoke to me, because it felt like that’s what I was doing. Misinterpretation is a novel about standing at the border and claiming that as your reality. The translations, interpretations, everything—it happens because you are on a border. That’s your reality, so that’s where you have to exist.

It’s funny, because when you finish a novel, what you’ve written doesn’t fully sink in until some time has passed. So one of the things I thought about recently is the duality of experience in the novel. Some of them are very obvious: you have the Albanian language and you have English. New York City and Tirana. But then I started thinking about how this duality extended also to other elements of the novel.

SA: Like the characters with legal status and the people who are in immigration limbo?

LX: Yeah, the path of a person who already has their papers and the person who doesn’t have their papers. There are so many instances of doubleness or polarity. The Kurdish woman who appears in the novel, that’s another path the narrator’s life could have taken, almost like another reality, so I was just thinking about how much I internalized this duality that it became a theme for the book.

SA: How did you approach using both Albanian and English in the text?

LX: Initially, I didn’t have a lot of the sentences that you see in Albanian. They were in English. My editor said, “Let’s have more sentences in Albanian,” so I started having more sentences in Albanian, and it changed my perspective of the text, in a way, because then I started looking at other sentences in English and thinking, “What would they sound like if they were in Albanian?” And then I started thinking, “What would this whole novel be like if it was written in Albanian?”

SA: That’s fascinating, because I think the characters in the book act differently when they speak in different languages and when they’re in different countries. So, it makes sense that your writing might take on different characteristics depending on which language you’re writing in.

That’s why we read, right? So that we can realize that we have enough things in common with each other.

LX: Just those few sentences with these two elements together—the Albanian and the English—brought up so many questions.

SA: Circling back to immigration, I appreciated how the book digs deep into different immigration stories. Many of the characters are in really complex and precarious positions. Like Zani, who was promised asylum in exchange for offering information about a crime, but the process doesn’t go as planned. What kind of research did you have to do to create these backstories?

LX: I’m a little bit afraid of research, because I feel like it kind of paralyzes me. So, what I tend to do is: I look things up, and then I let a lot of time go by, so that it’s not so fresh in my mind, and then I use whatever has stayed in my mind. And maybe what has stayed was also the most interesting part of it. So I did read about somebody who was promised asylum for collaborating with the U.S., but it somehow didn’t work out. So, yeah, I did some research for these situations.

SA: As we discussed, art can be interpreted or misinterpreted in many different ways, but what’s something that you hope the reader understands about “standing on the border” as a result of reading about these characters?

LX: I hope they find commonalities with their own lives, even if they’ve never heard of Albania, or they don’t know what is on the map. No matter what, I hope that they read it and they realize, “This person has such a different culture, and their background is so different from mine, but I feel like I can relate to them.” I also think the description of the novel necessarily focuses on some of the darker aspects of the plot, but I’d like to think that the book is a little bit more colorful and has more hope, more nuance. So I hope people see that side of it. But yeah, finding things in common. I mean, that’s why we read, right? So that we can realize that we have enough things in common with each other.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.