In 2004, an 11th-grader named Judd Cramer at Mountain Lakes High School in New Jersey was assigned to read the 1925 novel The Great Gatsby. “I did not engage with it as much as I wish I had,” he explained to me a few years ago by email. “I only studied what was necessary for the test—themes, etc.” But several years later, in 2011, he read it again. This time, Cramer wasn’t a student; he was working as a labor economist for the Obama administration’s Council of Economic Advisers. As an adult, he “enjoyed the book much more and could relate to the selective stories that people tell about themselves, especially in a city like Washington, D.C.”

Later that year, the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, Alan B. Krueger, was writing a major speech on “The Rise and Consequences of Inequality.” In preparation, Krueger asked his staff for suggestions as to what to call the inverse relationship between income inequality and intergenerational mobility. The more unequal the society, the less opportunity there was to realize the American dream (here defined as rising above the circumstances of one’s birth and setting up one’s children for greater prosperity). And Cramer remembered The Great Gatsby. “Although Gatsby was able to acquire riches,” he explained to me later, “he was not able to ascend to the level of somebody who could pass that on to his children. He was gunned down. He could not last in the upper class.” Accordingly, “his story showed the large gulf in American society in the 1920s that was being reopened since the 1990s. One of the only ways to get out of poverty for him was a life of crime because the upper classes were so far removed from his upbringing.” All this was why, in 2011, Cramer suggested to Krueger that inverse relationship between income inequality and intergenerational mobility should be labeled “The Great Gatsby Curve.”

In his speech at the Center for American Progress in January 2012, Krueger used the chart of the Great Gatsby Curve (GGC) to predict that “the persistence in the advantages and disadvantages of income passed from parents to the children” would “rise by about a quarter for the next generation as a result of the rise in inequality that the US has seen in the last 25 years” (see figure 1). In other words, the trajectories of rich families and poor or working-class families would continue to diverge. “Not since the Roaring Twenties has the share of income going to the very top reached such high levels,” he said. “It is hard to look at these figures and not be concerned that rising inequality is jeopardizing our tradition of equality of opportunity.”

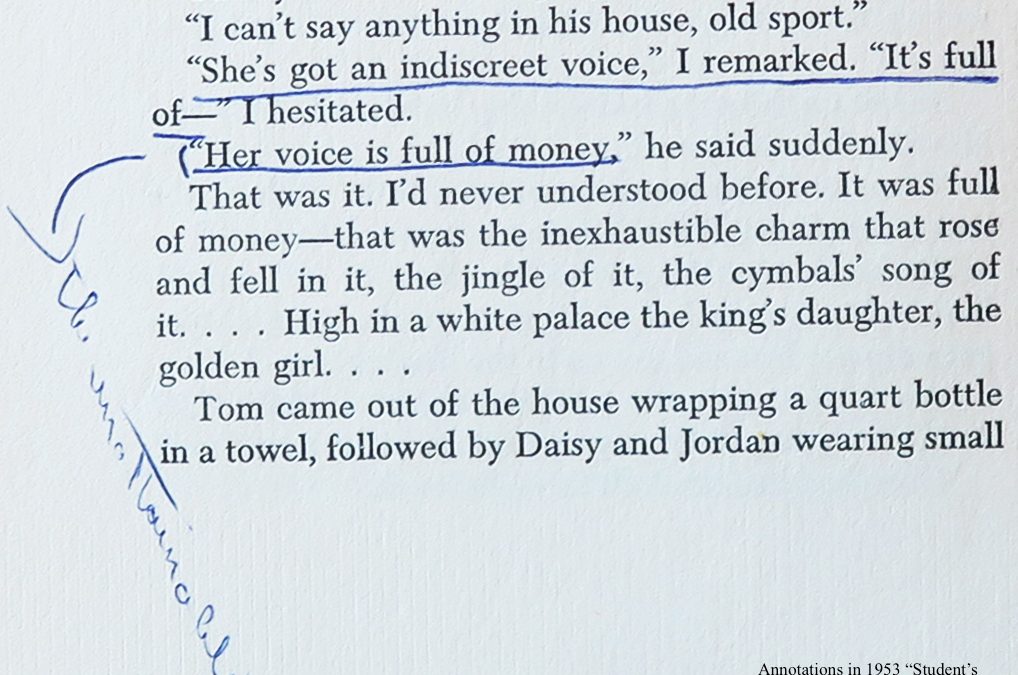

The introduction of Gatsby into the lexicon of economics completes a chiasmus, because economics have long been part of the study of Gatsby. For example, in “The Romance of Money,” the much-cited introduction in Three Novels of F. Scott Fitzgerald (1953), Malcolm Cowley wrote that Gatsby “revealed the new spirit of an age when conspicuous accumulation was giving way to conspicuous earning and spending.” Thus issues of class, inequality, and economic mobility entered the high school English curriculum. For the most part, it was presented as a cautionary tale. “The American dream is not to be a reality, in that it no longer exists,” wrote the English professor Roger Pearson in a 1970 article for The English Journal, “except in the minds of men like Gatsby, whom it destroys in their espousal and relentless pursuit of it. The American dream is, in reality, a nightmare.”

For many of Gatsby’s student readers, the novel has been an occasion to consider their own aspirations and the opportunities to realize them. Moreover, insofar as education, or educational inequity, is one of the factors that determines the gradient of the GGC, Gatsby itself has played its own small part in the viability of the American dream. As “the one American novel that most educated Americans have read,” Gatsby has been a middle-class attainment, demonstrating the sort of literacy associated with college eligibility and professional success and the “kind of knowledge-capital,” in John Guillory’s phrase, “whose possession can be displayed upon request and which thereby entitles its possessor to the cultural and material rewards of the well-educated person.” In that sense, responses to test questions about the symbolism of the eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleberg or the “green light” at the end of Daisy’s dock have significance beyond the classroom.

Gatsby’s centenary is an occasion for looking back at its history: its publication by Scribner’s on April 10, 1925; its commercial failure and quick consignment to Jazz Age ephemera; and then, beginning in the 1940s, a surprising resurrection and a deferred critical appraisal as a masterpiece, such that in 1998 it was ranked by the Modern Library as the second best novel of the twentieth century, after only Ulysses. But literary history has paid little attention to Gatsby’s vast scholastic readership. Today, according to a national survey of English teachers that I conducted with the historian of English education Jonna Perrillo, Gatsby is the most frequently assigned novel in American high schools.

So the story of Gatsby, Nick, Tom, and Daisy is also, much more importantly, part of the history of hundreds of millions of student readers and their teachers, spanning eight decades. In researching this article, I spoke to teachers and former students, because the significance of Gatsby lies not simply in its representations but in how it has been taught and understood.

In his speech on “The Great Gatsby Curve,” Krueger did not say anything at all about Fitzgerald’s novel. But had he been so inclined, he would have found plenty of evidence to support his thesis. Not only did Gatsby fail, but Nick’s father had been able to “finance” him for a year as he started out in “the bond business,” and Tom, whose “family were enormously wealthy,” had the means to bring along “a string of polo ponies” in moving from Illinois to East Egg. Myrtle and George Wilson had zero chance of escaping the Valley of Ashes. “‘Don’t talk so much, old sport,’” Gatsby commands his houseguest, Klipspringer, as he gives Daisy a tour of his mansion. “Play!” The song his guest plays on the piano previews the GGC:

One thing’s sure and nothing’s surer

The rich get richer and the poor get—children.

Krueger noted, “Children of wealthy parents already have much more access to opportunities to succeed than children of poor families.”

It follows that the children of wealthy and poor parents have different experiences with Gatsby. At well-resourced, majority-white suburban schools like Judd Cramer’s alma mater, where only .01 percent of students are eligible for free lunch, the study of Gatsby may be part of the intergenerational transfer of “knowledge-capital.” In contrast, at Bryan High School in Omaha, the entire majority-Hispanic student body is free-lunch eligible. Ilene Sigman finds that her students struggle to relate to the “extreme wealth, unimaginable wealth” depicted in the novel, as she told me recently via Zoom.

“I don’t think they’re opening Gatsby and being like, I don’t see myself in here”—she threw an invisible book over her shoulder—“they do find it a fun story, regardless, especially the romantic elements of it.” But they also have difficulty with the language. Sigman no longer uses Gatsby for whole-class reads, but rather includes it as a choice for literature circles, along with more accessible options like John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.

A school where students actually look for themselves in Gatsby, where they look forward to the unit on that novel as a rite of passage, is Great Neck North. As an 11th-grader there recently pointed out in a masterful article for the F. Scott Fitzgerald Review, the school is constructed on a parcel of what was once Nirvana, the 125-acre estate of William Gould Brokaw. When we spoke, Brian Hartwig had just finished teaching Gatsby in one course and was preparing to do so in another. In fact, Hartwig actually has a student who lives in the house where the Fitzgeralds had lived when F. Scott started the novel. But the students at West Egg High are not the descendants of the partygoers from the Jazz Age. Today the school is populated largely by the children of Persian Jewish and Asian immigrants.

The students of Great Neck North, according to Hartwig, come into the unit knowing Gatsby as a “meme”: Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby holding up a glass of champagne (figure 2). “It’s not that I take pleasure in it,” Hartwig said, “but it’s exciting for me to demystify or to get rid of all the allure of Gatsby and really think about what the text is, because I think, like anything else, it’s a hundred years old, and it’s become a million different things.”

Figure 2. The Gatsby Toast

Our survey finds that Gatsby is still taught in all kinds of schools, across every demographic. Often it’s as a required text or as a selection from a list of approved titles. In an era of high-stakes testing and diminished reading stamina, when an 11th-grade class might read only two or three books in a year, one of them is likely to be Gatsby. It’s a safe choice. If one were looking for them, the novel offers plenty of pretexts for challenges, but it’s not the sort of book Moms for Liberty is gunning for.

With its white male privilege, Gatsby is also the antithesis of a culturally relevant text selection. Anna Roseboro, now retired from the classroom, encourages her mentees in the NCTE’s Early Career Educators of Color program to eschew the canon and teach works that are more relatable for students. But in over four decades as a classroom teacher, she taught Gatsby as a required text at a variety of schools in four different states.

“I don’t think any good text is disconnected,” she said. “Our job as instructors is to provide the bridge, and invite students to notice what is similar. And the same thing about economic differences: Who’s in? Who’s out? Who makes the money? Who doesn’t?” At an independent school in La Jolla, she had students “crossing the border from Tijuana every day,” and others who were East Asian immigrants: “Almost everyone could connect. They knew of it. They were in one of the classes that was addressed in the book. And they knew how they were perceived.”

Except not all English teachers, historically, have sought to facilitate personal connections with literature. One of the keys to Gatsby’s curricular ascendance is that it lends itself so well to the sort of formalist, self-contained analyses that dominated college English at mid-century and is still enforced by state standards. For example, Patrick Grant, who earned his BA in English from the University of Maine in 1969, was typical of his generation of teachers, trained in the New Criticism: He aimed to teach his students at Brewer High School in Maine about literature itself. “I think maybe he wouldn’t have been surprised,” says his former student Tanya Baker, recollecting her personal “vision altering” experience of reading Gatsby and then The Grapes of Wrath in his class during the 1980s. “I think he probably had a very personal relationship with literature himself, but I think he didn’t choose a set of texts to be like, ‘You’re white people from Bangor, Maine, and your families haven’t gone to college, and here’s a juxtaposition of two books that will blow your mind.’ I don’t think that.” Now the Executive Director of the National Writing Project, Baker began her career teaching English at Brewer, her old high school, where she taught The Great Gatsby.

“There’s something so beautifully perfect about that little novel,” she said. “I think many young people growing up in the United States, in the particular culture that we live in, yearn for things that they don’t understand the costs of, and for a kind of life that they see represented around them. But they don’t understand why some people have it and some people don’t, and why. What would it take to access it, or if it’s even possible to access it. And in The Great Gatsby is sort of the perfect characterization of that desire that we’ve been fed, and it’s so poignant.” Her words made me reconsider my own ambivalence about the novel, as well as its curricular uses.

“I just think it stunned me when I was 17,” she continued. “And I taught it for 10 years when I was a high school teacher—it stunned other kids. You know it stunned kids. And it’s so little, and there’s so much. You know, people will talk about the purple prose, but it’s like … so American, actually, this idea that we can build something extraordinary—”

“And then have it come crashing down,” I interjected.

“And then have it come crashing down,” she agreed, “without ever really recognizing what it costs.”

high school English may aim to equip students for success, but the literature keeps reminding them of the barriers.

So American. If “Gatsby were around today,” wrote Adam Cohen in a 2002 New York Times editorial, “he would probably be in the upper echelons of Enron,” the energy company that went bankrupt after being implicated in a massive fraud. “The Great Gatsby has often been described as a portrait of the American dream gone bad,” wrote David Dowling in the 2006 NCTE volume The Great Gatsby in the Classroom: Searching for the American Dream. “It has remained a force in American literature because it captures well the conflict between wealth and the values that are the foundation of this country, leading the reader to question the belief that honesty and hard work will lead to success.”

A year later, the subprime mortgage crisis set in, revealing that a central pillar of the American dream, home ownership, had become a pretext for fraud and predation. Across the sunbelt, Gatsbyesque McMansions were overrun with ashes.

In February 2008, a month before the collapse of Bear Stearns, a headline appeared on the front page of the Sunday New York Times: “Gatsby’s Green Light Beckons a New Generation of Strivers.” The article profiled teachers and students doing Gatsby units at two Boston High Schools: the highly selective Boston Latin School (BLS), the oldest public school in the country, and the Fenway School, a small early college school founded in 1983. Alongside the lede was a photo of a 14-year old BLS student, with the caption “Jinzhao Wang, who immigrated from China, found ‘The Great Gatsby’ inspirational.” The reporter had visited Wang’s class, where students had written “their own ‘green light’” on a green construction paper cutout of a light bulb. Responses ranged from “Complete college with a good degree” to “M/B/Tri-illionaire.” Wang told the reporter that her “green light is Harvard”; the allusion was apt, because the bastion of old money and privilege lay just across the water from the Allston neighborhood where she lived.

“I can’t believe it’s been 17 years,” Wang told me via Zoom. She recollected going downstairs to CVS to pick up the newspaper. It was exciting, but not “a huge deal,” because “there were so many other things to worry about.” They were recent immigrants from China, and Wang had a new baby sister. Wang spoke to me movingly about her mother’s traumatic isolation growing up during the period of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, when her grandparents worked in the fields until late at night. “So I guess the American dream for my mom was to have a second daughter or second child,” which was prohibited at that time in China. Her father, at the time a visiting professor, and mother, who taught Chinese in public schools, chose to stay in the US for their daughters’ educations. Wang’s sister ended up following her through Boston Latin to Harvard.

Yet even then there had been “a green light beyond the green light,” as Wang told the reporter in 2008. That is, she had sought a Harvard education in order to contribute to China’s economic development. She still has that goal. Now a financial analyst at Bloomberg, she works with mortgage-backed securities—“much safer now”—and Chinese investors are a huge market, so an eventual move to China is possible.

So her American dream was subordinated to a Chinese one, traumatically rooted in her family history. Yet Wang also emphasized that she has come to learn that this notion of green lights, of means and ends, is simplistic; she is still making sense of her journey. She plans to reread Gatsby.

As Wang’s story shows, BLS, where about a third of the students are classified as “low income,” is a gateway to socioeconomic mobility. So too is the nearby Fenway School, but prosperity is a further reach. According to the Massachusetts Department of Education, 73 percent of Fenway students are “low income” and 83 percent are “high needs.” Fenway is one of about 20 “pilot schools” in Boston, with greater flexibility in staffing and programming, intended to model innovation for public schools.

The Fenway School’s slogan is antithetical to Gatsby’s vision: “Work Hard. Be Yourself. Do the Right Thing.” In 2008 Nicole Doñe, now an interior designer, dismissed Gatsby’s aspirations as “a white poor man’s dream”; she told the New York Times reporter that “the American dream is working hard for something you want. It’s not about having money.” But one of her classmates, Harkeem Steed, disagreed: “The American dream has a lot to do with money,” he said. He “compared Gatsby to his hero, Jay-Z.” It was a prescient comparison: The association between Gatsby and the hip-hop mogul would be cemented five years later by Baz Luhrmann’s Gatsby movie, for which Jay-Z executive-produced the soundtrack. The updated Queensboro Bridge scene featured “a drop-top car full of glamorous African Americans, drinking champagne and dancing to Jay-Z’s ‘H to the Izzo.’”

But in recollecting his Gatsby study in a recent interview, Steed invoked a different Jay-Z song. He was from “the projects”; he had been exposed to economic inequality in America through “past due bills, eviction notices and things like that.” But Jay-Z was from a similar background and had inspired Steed to think that he could make it too. He was still a huge fan. As he recalled, the parallel between the fictional character and his real-world icon made him like the book more. Their class project, at the time, had been to create a sort of personal narrative, and Steed used Jay-Z songs to articulate his own story, ending with “I Made It,” from the 2006 album Kingdom Come. Back in high school, Steed had looked forward to saying, like Jay-Z, “Mama, I made it.” Now, in 2025, he’s the Director of Services for the Westin Boston Seaport, supervising a staff of about 120. “I’m not, like, a millionaire,” he told me, “but I definitely feel like I made it. I’m educated. I’m a homeowner. I have kids. I don’t have any past due bills, right? No student loan debt and things like that. So definitely in my own circle, I’ve achieved the American dream.”

Steed had a strong, positive recollection of Gatsby and his English class, especially because of the reporter’s visit, but in our conversation he kept referring to a required program called “Ventures”—intended to foster financial literacy, networking, and business skills. It’s a rarity in public education. Along with other alumni, Steed recently returned to Fenway to join a panel at the career fair. “So it’s just awesome to just keep it a full circle,” he said. “It’s a very close-knit community, and a lot of us keep in touch until this day.”

I spoke to one other person quoted in that 2008 article: Kay Moon, a teacher at Boston Latin. Back then, as a new teacher, she worried she’d be “pink-slipped,” like so many others during the Great Recession.

She now reflected on the years she spent teaching the Gatsby unit to 10th graders. It had been fun for the students to go into the novel with that green light bulb exercise, identifying with Gatsby’s faith in wish-fulfillment. But they also recognized the impediments. “I think it was the kids who brought up early on, even back in 2008, the disparity though.” They had remarked on Tom’s gatekeeping, his refusal to recognize Gatsby’s money as having the same value as his own. “So the kids were the ones that were very astute in bringing up class divides even before we really kind of brought it up,” Moon explained. “And again, the book is pretty easy in that sense, like, West Egg, East Egg, you know.”

Moon’s students weren’t taken in: They saw Gatsby’s failure to attain his green light as emblematic of the “modern day” reality of the American dream, “nothing that people can actually reach any longer … a good utopian idea, but it’s not really feasible anymore.” Moon shifted into the present tense: “Yes, one or two people might be able to get it once in a while. But the American dream is dead as far as they’re concerned.” At the same time, they were Boston Latin students, and they still believed that their hard work would pay off.

Other teachers I spoke with reported similar discussions with their students around Gatsby. Nathan Morrill, who teaches English and coaches football at a public school outside of Waco, Texas, prompts his students to think about their life goals in relation to Gatsby’s characters. Many “connect more” with the realistic Nick than with the fantastical Gatsby. Yet “unfortunately, a lot of my kids today feel the American dream is almost dead.”

Morrill is devoted to helping his students who don’t have the resources of family wealth to develop the language, writing, and thinking skills that enable college and career success. In that sense, his mission is aligned with the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills standards (TEKS). Still, he made it clear that his pedagogical green light glows from well beyond the short-term horizon of standardized examinations.

“My students told me the American dream was a nightmare,” said Neisha Terry Young, echoing that 1970 article in English Journal. Formerly an English teacher at the now-defunct M.E.T.S. Charter School in Jersey City, Young is now my colleague, as an assistant professor of English education at Stony Brook. “And I had someone else say: ‘Well, the American dream. Only some people are allowed to even have the dream, right?’ Only some people. Others are awake.”

Young herself is an immigrant from Jamaica, and she read Gatsby for the first time in preparing to teach it. A majority of her students were Hispanic or Black, and many were Muslims. They had a lot to say, and write, about the religious representations in Gatsby, such as George Wilson’s fixation on the eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg. Young looked at notes and student papers on her computer as we Zoomed.

“We spoke about capitalism. And wealth, and who has it and who does not.” The discussion of Gatsby became a critique of capitalism, how the system “creates these groups, the haves and the have nots and what determines who is in which group and who gets to come into the group and who does not.”

Young’s students easily identified with Gatsby’s longing gaze eastward across the water. “We were living in an economically less advantaged area of Jersey City, and were right across the river from the glitz and glamour of New York.” She had them consider: “What do you give up to get there? What did Gatsby give up in the end? At the end of it all, he still didn’t fit in. He still didn’t belong.”

With several of the teachers, I reflected on the American dream canon—Gatsby, Of Mice and Men, Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, which today is the most commonly assigned work by an African American author—and how it collectively offers hardly a glimmer of hope. It’s a canon that coalesced during the Cold War. And yet, no Soviet propagandist could have come up with a more dismal composite of the American Way of Life.

So high school English may aim to equip students for success, but the literature keeps reminding them of the barriers. And we have yet to arrive at an era in which these pessimistic representations from the past are not also portraits of our present, although in some periods the parallels are closer than in others. If The Great Gatsby is indeed a cautionary tale, then, in its centennial year, what have we to celebrate?

At least, we can celebrate great teachers. ![]()

This article was commissioned by Nicholas Dames.

Featured image: The Great Gatsby – Autograph Manuscript; F. Scott Fitzgerald Papers, C0187, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.