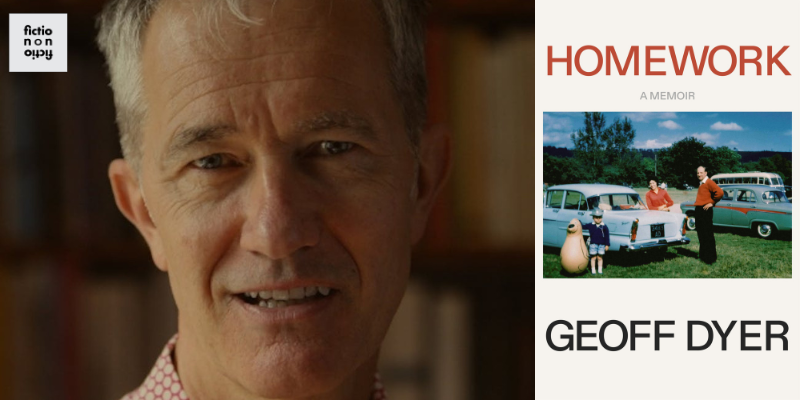

Writer Geoff Dyer joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new memoir Homework, which covers Dyer’s working-class youth in England during the 1960s and ’70s. He recollects his early passion for reading and film and reflects on writing about his parents, as well as the intensity of childhood play and collecting in the wake of the Second World War. He also explains what it meant for him to pass the 11-plus exam, a test given to British 11-year-olds to determine if they could go to grammar school—and the peculiar role that grammar schools played in the British educational system. Dyer talks about how this opportunity made his eventual admission at Oxford possible. He reads from Homework.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/. This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, Hunter Murray, and Janet Reed.

Homework: A Memoir • The Last Days of Roger Federer • See/Saw: Looking at Photographs • “The Secret of Who She Was” |Harper’s Magazine • “Best seat in the house: writer Geoff Dyer on why sitting in a corner is so satisfying” | The Guardian

Others

Lord of the Flies by William Golding • An American Childhood by Annie Dillard • My Sky Blue Trades by Sven Birkerts

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH GEOFF DYER

Whitney Terrell: I think play is really important. I have two sons who have gone through the periods of play that you talk about, and I was struck by how free and present you were when you played with other kids. You know, there’s a lot of motion and conversation and acting out in the war, fighting in that green space or road. Today’s play seems dominated by the internet, video games, television. I wonder if you could talk about the importance of play and writing about play, and what you were trying to capture there in those sections.

Geoff Dyer: Yeah, there’s two aspects of this, I think. One, I was born in 1958 so the Second World War was over by then, although it’s worth reminding an American audience that rationing in Britain continued into the 1950s because, of course, we were completely bankrupted by it. But the Second World War was so present in the culture. It was being replayed on the TV and comics and all this kind of stuff. We were all the time playing at war. But the crucial thing is that it was wonderfully unsupervised. We were just left to—not run riot, but in the lanes behind our house, where every house had kids, we all just got together, and the play was— there was a lot of rough and tumble.

But we never set fire to anyone. There was never any Lord of the Flies quality to it. So there were injuries and upsets and tears, but no one came to any harm. And also the school was, let’s say, a 10-minute walk away, and we, from a very early age, after the first couple of days, we didn’t get taken there by our parents. We all walked there in a gaggle, which was, of course, a lot more fun. It wasn’t this constant, terrified monitoring of kids, and it’s not—now there’s a fear that pedophiles lurk around every corner. There was none of that sort of stuff. It was rather wonderfully unsupervised, and no one came to any harm.

WT: There was one ritual that you described that does not have an American equivalent that I wanted to hear you talk about, and that is conkers. Could you explain those to our listeners?

GD: So these were horse chestnuts and they would fall from the trees in their spiky shells, and then you’d put a hole through them, tie them to a to a string, and then you’d have these competitions to try to bust somebody else’s conker. The idea was that the harder you hit somebody else’s conker, the greater the chance there was of winning. But in retrospect, I can see that was irrelevant; it was pretty arbitrary whose conker was going to get smashed. The idea was that the value of your conker— you would inherit, as it were, you would amass all the accumulated victories of the conker you were fighting so you could, after one competition, have a conker that was worth two hundred or something. Then there would be these rather tragic—mad in the sense of mutually assured destructive episodes when the two conkers would destroy each other, and all of that accumulated value, all of the rich history of the civilization of the conker would be wiped out, and we’d effectively be bombed back to the Stone Age. I suppose there’s a parable lurking in that, but I’m not sure what it is.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: I want to point out for our listeners—who should definitely pick up this book—that one of the epigraphs is from Lord of the Flies, and it’s one of the children saying, “I got the conch.”

GD: I should explain that. I’m glad you’ve raised this, because I liked that “I’ve got the conch.” It’s that rule they established that means you’re the speaker in the Senate. Anyway, “I got the conch,” four words, the Golding estate wanted some phenomenal amount of money for that. And I pretty well despise the heirs of these things who often have done nothing themselves except accumulate money for what their parents have done. So it was a straight choice, either pay up or not use it. It was a really great source of pleasure—I said to the publisher, okay, great, we won’t use it. So it’s gone. That was just in the proof copy.

WT: Oh, we got the ARCs, okay, I see. That’s interesting. We got to read something, listeners, that you will not get to read. It’s insane to make you pay for it. Just at the beginning of the book. It’s just a quote.

GD: I think under American law it is fair game, but under British law, I would have had—the idea that I’d be paying, effectively, fifty pounds for a word, three of which were “I got the…”—that seemed excessive. I mean, when somebody’s preparing a legal document, you have to pay that kind of money.

VVG: I was just about to ask you about that, because I thought, is it in the American version?

GD: Yeah, actually, it all worked out well. So, late in the day I decided there was a much better quote from Annie Dillard’s An American Childhood. So we’ve got that in the American edition now.

VVG: Okay, well, listeners, get yourself to the store. You can find the version that Whitney and I do not have. We will get ourselves to the store as well and catch up on this. But that’s fascinating because under American law, it would just be fair use.

GD: It seems like it’s a good principle, that. Also, crucially, Annie—even if I did have to pay, which—Annie Dillard is still alive and I know her a bit, but I don’t think she’ll be—anyway, so it’s all worked out. I’ve got a better epigraph.

VVG: It’s fascinating that you’re talking about the wildness of unsupervised play. I think about the contrast with the really overscheduled, heavily supervised version of play, also often very digital or simulated as opposed to actual. But also, out of the play that you described, there are these mini systems, like in Lord of the Flies, self-governance, or mini markets of your— like, I was not a collector of baseball cards. I watched my brother do that, I built the card houses and knocked them down, but I wasn’t collecting them. And to see the ways that commerce arises or these little systems of value, and then they’re so quickly dismantled.

Not only is play a huge part of this book, in the loveliest way, but of course, the book is also about your intellectual development. We’ll talk more about this a little bit, because you mention a ton of books, which I definitely want to talk about. But in the intro we were talking about you took what was called an 11-plus exam to get into Grammar School, which was an extremely competitive process. These schools don’t really exist in exactly the same format so, for our listeners who aren’t familiar with these educational structures, can you explain what a grammar school is and how this has changed to today?

GD: Yes, I thought this school stuff would be a source of great confusion, because, as you know, here in Britain, when we say public school, that’s what you call a private school. Anyway, for people who go to state schools in Britain, there was this exam at eleven, and it was a sort of IQ test, really. On the basis of that, you’d go to one of three schools: you’d go to a secondary modern school, which, in my case, that was a continuation of the school I’d been at, anyway the same geographical location, or there’d be a technical school, technical, it was called the tech and then at the top, for the top percentage, you would go to this thing called a grammar school, where you would receive a really excellent education, free, provided by the state.

Once you were at a grammar school, it was very likely you’d go on to do these exams. At sixteen, you do O levels— you’ve got to stay at school till you’re sixteen— and then you’d go on to do A levels. From there, you’d go on to university. At my particular grammar school, a famously good grammar school, there was such a tradition of people staying on for A levels and going on to university, and not just to university, but to Oxford and Cambridge. So I was lucky enough, and I passed the eleven-plus.

But it’s really important to stress something, this all sounds like a nicely benevolent thing and a force for social mobility— and it is, if you’re one of the lucky ones that pass, as I did— but the purpose of the eleven-plus was actually the opposite of what it appears. That is to say it was designed to ensure there’d be a steady flow of kids who didn’t pass the eleven-plus, who failed, who would continue on to secondary modern school and go on to trades, apprenticeships, to work in factories and all this kind of stuff. So at the age of eleven, if you fail, your options in life are really, really limited. And then actually, for the kids who pass, that’s, as it were, the flip side of the real, or the corollary of the other purpose for it. It’s, of course, terrible that your destiny is decided at the age of eleven— as a principle that’s awful.

But I can’t help but feel a sense of gratitude for this inherently unjust system. Because it was unjust, the labor governments pledged themselves to replacing it with this idea of the comprehensive school, whereby everyone in a certain geographical area would go to the same state school, so there’d be that they would remove that thing, and that’s a nice idea. The great problem is that comprehensive schools very soon stopped being comprehensive, because a certain part, often the most motivated part, they’d be siphoned off into what we would call the public schools, and which confusingly, you in America— but perhaps more correctly— call private schools.

And this antagonism is so crucial to British life. It’s quite distinctive. I think in America, typically, if somebody’s been to a private school, you would just say, “Oh, they went to a private school.” But someone like me in Britain— it’s caused me so many problems in America, because I tend to use the phrase “public school” in a pejorative way. And by public school, of course, what I really mean is private school.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Geoff Dyer by Guy Drayton.