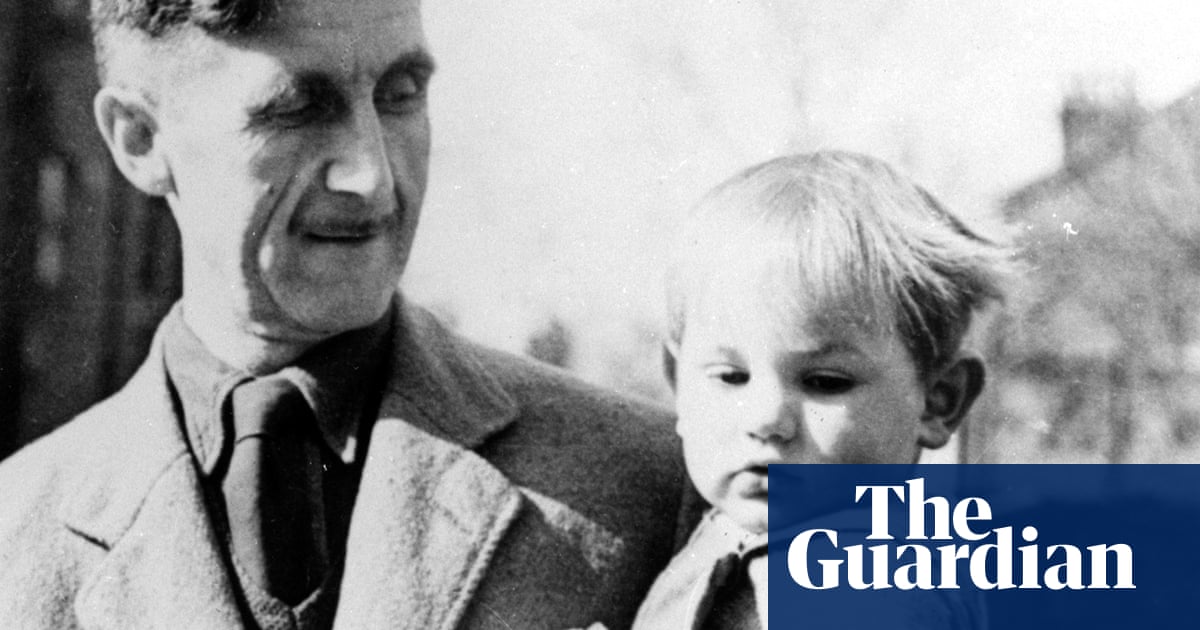

Richard Blair didn’t have the easiest start in life. At three weeks old, he was adopted. Nine months later, his adoptive mother, Eileen, died at 39, after an allergic reaction to the anaesthetic she was given for a hysterectomy. Family and friends expected Blair’s father, Eric, to un-adopt him. Fortunately, Eric, better known as George Orwell, was an unusually hands-on dad for the 1940s.

Orwell and Eileen had wanted children for years, but he was sterile and it is likely that she was infertile as a result of uterine cancer. Having finally agreed to adopt after their struggle, Orwell was not going to give up on his son. “The thing he wanted most in life was to have children,” says Blair. “And now I was his family.”

We are in the kitchen of Blair’s home and he is making me a cuppa. On the kitchen wall is a framed poster of his father’s famous instructions for making tea. “Use tea from India or Ceylon (Sri Lanka), not China,” it starts. “Use a teapot, preferably ceramic. Warm the pot over direct heat. Tea should be strong, six spoons of leaves per litre. Let the leaves move around the pot. No bags or strainers. Take the pot to the boiling kettle. Stir or shake the pot. Drink out of a tall, mug-shaped teacup. Don’t add creamy milk. Add milk to the tea, not vice versa. No sugar!”

Orwell, perhaps the most influential writer of the 20th century, railed against totalitarianism in his dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four; chronicled it in his memoir about fighting in the Spanish civil war, Homage to Catalonia; and satirised it in his wonderful fable Animal Farm. Yet it has to be said his tea-making rules verge on the autocratic. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised. Orwell, who died at 46 in 1950, was a cauldron of contradictions – a single‑minded rebel so concerned about embarrassing his parents when writing about homelessness that he adopted a pen name; an Old Etonian man of the people; an introverted party animal; an egalitarian socialist and bigot; a man who railed against the “incorrigible dirtiness and untidiness” and the “terrible, devouring sexuality” of women, but who lived in filth and devoured as many women as possible.

Blair apologises. No teapot, no leaves; he is making do with a teabag. “It is from Harrods, though!” He is 80 years old, just like Animal Farm. Blair hands me the tea in an orange-and-white mug designed like an old-fashioned Penguin book cover of Nineteen Eighty-Four. “Biscuits?” He gets out the chocolate digestives. On the table is a copy of today’s Daily Telegraph.

You couldn’t imagine two more different men. Orwell was a puritan radical; Blair is a “leftwing Conservative” who says he could never vote for Labour because he can’t bear the thought of singing The Red Flag. Orwell detested the privilege into which he was born and spent much of his life living in squalor; Blair lives a cosy, suburban life in a pretty, middle-class village near Leamington Spa in Warwickshire. Orwell was a police officer in Burma, now Myanmar; ran around with revolutionaries in Spain, where he got shot in the throat; lived on the streets in London; hung out in brothels in Paris; and retreated to the remote island of Jura towards the end of his life to write Nineteen Eighty-Four. Blair, meanwhile, started out as a farmer before training people to sell tractors, finally ending up as a landlord for holiday cottages in Craignish on the west coast of Scotland.

Yet Orwell has shaped his life. “My father was devoted to me,” he says. “Absolutely devoted.” And Blair is equally devoted to him. He regards himself as the keeper of the sacred flame for his father.

Blair, a broad man with caterpillar eyebrows and an establishment air, looks out over his large garden and says if he had been sensible he would have bought the plot of land next to their house; it would be worth a fortune now. On a shelf in the hallway, we pass a maquette of the Orwell sculpture that stands outside Broadcasting House in London. He is instantly recognisable – thin as a pipe cleaner, gangly (he was 6ft 2in, or 1.88 metres, tall), pencil moustache, waves of dark hair, fag in hand.

Opposite is a mounted plaque featuring a slab of slate and an illustration of a white stone house. Underneath, it says: “This fragment of slate came from the roof of Barnhill, Isle of Jura, which Eric Arthur Blair (George Orwell) rented from May 1946 until his death in January 1950. It was here that he wrote his final great novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.” This handsome memento is signed “Richard Blair, Patron of The Orwell Society”. He tells me he got the slate when the roof had to be replaced and sells the plaques for £60 a pop.

After Eileen’s death, with his health declining as a result of the tuberculosis that would kill him, Orwell looked for somewhere suitably remote where he could focus on writing and Blair could enjoy the freedom of nature. His friend David Astor – the editor of the Observer, for which Orwell wrote, from 1948 to 1975 – had a home on Jura and suggested it would be perfect for their needs. When Blair was two, father and son headed to the island, accompanied by a nanny and Orwell’s younger sister, Avril. It was here that Blair got to know his father.

Young Blair and Orwell were a solid team. Orwell continued to do things on his own terms, as he always had. Work took priority; he went on trips when he fancied or was commissioned; and he continued chasing women, asking at least four to marry him after Eileen’s death, until Sonia Brownell finally agreed to become his second wife on his deathbed.

But as far as Blair is concerned, Jura provided a father-son paradise. “I loved it. Here I was in a farmhouse, well shod, had clothes, plenty to eat, and I could roam anywhere I liked, which you couldn’t do in London. Just a fabulous place to live.” There were no other children, but it didn’t bother him. While his father wrote, Blair explored. They would meet for breakfast and high tea, cooked by Aunt Avril. On summer evenings, he and his father would go out fishing for crab and lobster.

They had so many adventures together, most involving an element of danger. Blair tells me of the time his father was making a wooden toy for him in his shed while he watched from on high, standing on a chair. Blair fell, crashed into a china jug and cracked his head open. Then there was the occasion when Blair, now a mature three-year-old, found a pipe, stuffed it with tobacco and over lunch asked his father for a light. “The lighter was passed surreptitiously, without breaking the conversation, behind his back. I tried to light this pipe and got something going. Of course, you can imagine what happened next. Sick as a cat.”

Most memorable was the time Orwell misread the tide when they were out in the hazardous Gulf of Corryvreckan, home to one of the world’s biggest whirlpools. Their dinghy overturned and they almost drowned. Did that shock Orwell? “I think it gave him a hell of a shock, yes, absolutely.” Was his father as reckless with you as with himself? Blair smiles. “Well, health and safety didn’t really rear its ugly head in those days, did it? And yet we survived.”

There was one precaution Orwell did take. “He said I had to have a pair of decent, stout boots, because of the snakes. Jura has got a lot of adders. They’re not desperately poisonous, but he had a thing about snakes, probably because of his days in Burma.” Was he scared of them? “Yes, to a degree, but not scared enough that he wouldn’t stamp on them and kill them.” Orwell treated his son as a mini-adult, perhaps not surprisingly, as he had little experience of children and there were no other kids around.

But there were plenty of visitors – too many, according to Avril, who worried that they distracted Orwell from his work and was aware that his time was limited. Blair says his aunt, who became his legal guardian after Orwell died, has been treated unfairly by biographers. “Avril has been described as a sourpuss. That’s absolute crap,” he explodes. “She was very protective of my father and was trying to stop a lot of stupid people wasting his time, coming to Jura and drinking his drink and just generally buggering around and stopping him from getting on with what he wanted to do.”

Who were these wasters? He mentions the poet Paul Potts. “God, he was a ghastly man.” Why? “He was just a disgusting old man. He could probably survive on the food that he got in his tie for about a week.” Did Orwell think he was disgusting? “They seemed to get on well. I think my father tolerated him. Paul Potts loved him and thought he was wonderful.”

But Orwell spent so much of the time in his bedroom, writing, sleeping and being ill. Was Blair aware how ill his father was? He shakes his head. “No, I was asking: ‘Where does it hurt, Dada?’ thinking it hurt like when I cracked my head open.” Towards the end, Orwell was hollowed out by his tuberculosis. Blair found out years later that his father was terrified of passing his TB on to him – and even more scared that they would become distant because he couldn’t show physical affection. “It’s all written down in the letters. He was frightened that I wouldn’t bond with him because he couldn’t give hugs or kiss me because he might pass on the bacillus to me.”

In January 1949, his father was admitted to the Cotswold sanatorium in Cranham, Gloucestershire. Blair’s final memory is visiting him with Avril a year later, by which time he had been moved to University College hospital in London. “A week later, an announcement came over the BBC’s Home Service, as it was in those days, saying the death has occurred today of George Orwell, author of Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

Did he know this was his father? “Yes, because there was so much consternation in the house.” That is incredible, I say, hearing about the death of your dad on the radio. He nods. “Yes. Did I cry? I probably did. At that age, you take these things in your stride, don’t you?” Blair was five years old.

He went to live on a farm near Jura with Avril and her husband, Bill. Uncle Bill, who had lost his leg in the war, taught him everything he knew about farming. Over time, Blair learned more about his parents. Did Orwell ever talk about Eileen? “No. I knew nothing about my mother until I read about her. We’re not a highly communicative family. I didn’t know I was adopted until I was about nine or 10. Avril was driving me somewhere and just dropped it in the conversation.” How did it make him feel? He laughs. “The impact was like a pebble in a pond. From a very early age, I was pushed around from pillar to post. When my mother died, my father had to find somebody to look after me while he was going away. So I would stay with all sorts of people.”

He had always known that Orwell was a writer. At 12, he read his work – first Animal Farm, then Nineteen Eighty-Four. “Those were the only two books that people read of his back then.” What did he think? “Well, I enjoyed Animal Farm. It was a jolly good book.” Which did he prefer? “Nineteen Eighty-Four was much more difficult to understand, to get the full meaning of it.” He admits he didn’t understand at the time that Animal Farm was an allegory about Stalinism.

Does he find it strange that words and expressions such as doublespeak, Big Brother and Orwellian have become common parlance? “Oh God, you can’t pick up a newspaper without finding a reference to this or that being Orwellian. And, of course, you stop and think: hang on, they’re talking about my father here.”

Blair went from the farm to farming college. He married Eleanor at 20 and they are still together. For many years, he did not benefit from Orwell’s royalties and lived modestly. Towards the end of his father’s life, Orwell’s accountant had set up George Orwell Productions, from which the author was paid a salary. After his death, the money held in the estate gradually disappeared. “Let’s call it bad investments by the accountant,” Blair says elliptically. Sonia battled for decades to regain control of George Orwell Productions. Days after she won her court case, she died. It took about nine years for the estate to be sorted. Blair was the sole legatee. He says the money started rolling in as the year 1984 approached, as publishers, TV companies and film‑makers cashed in on Orwell’s novel.

Have the royalties made much difference to Blair’s life? “Yes,” he says. He was able to buy the house we are in today. How long have he and his family been here? “Since 1984!” He smiles. “But that’s just happenstance.”

There could have been a dramatic change in lifestyle, he says, but he has erred on the side of caution. “I’ve supported the Orwell Foundation to some extent and the Orwell Society a little bit. Hopefully, there will be money for my children and grandchildren to inherit. My accountant said: ‘Richard, do you want to become a tax exile? Do you want to go to Spain?’ Which is what one did in the old days. Eleanor said she didn’t want to go to bloody Spain and become a gin-and-tonic refugee. So we stayed put and we’ve had to put up with all the taxes. Another biscuit?”

Since retiring, he has dedicated himself to his father’s memory. He goes abroad to give talks on Orwell and leads tours around Catalonia, showing people where his father fought in the Spanish civil war. Over time, he has become more of an expert on his father. Often, he says, he is not sure whether his knowledge is based on first-hand experience, what people have told him, what he has read or a mix of all three.

Orwell’s family had been well‑off, thanks to the slave trade. His great-great-grandfather, Charles Blair, was a wealthy Scot who owned plantations in Jamaica. After slavery was abolished in many of Britain’s colonies in 1833, the Blairs were one of 3,000 slave-owning families paid a total of £20m in compensation, the equivalent by one calculation of about £17bn today. But by the time Orwell was born in Motihari, in what is now the state of Bihar in north-east India, most of the family money had gone. His father, also Richard Blair, worked in the opium department of the Indian civil service. When Orwell was one, his mother, Ida, moved back to England, while his father continued working in India. He spent his childhood with Ida and his sisters in Oxfordshire.

His family would not have been able to educate Orwell privately if he had not won scholarships, first to St Cyprian’s prep school in Eastbourne, East Sussex, and then Eton. In a posthumously published essay, Such, Such Were the Joys, about his days at St Cyprian’s, he said he hated the place and was frequently made aware that he was “from a poorer home”. After Eton, he would have needed another scholarship to go on to university. His parents assumed he would not win one because of his poor exam results, so he enrolled in the Indian Imperial Police in Burma, which partly inspired his first novel, Burmese Days.

There are many biographies of Orwell, several of them controversial in one way or another. Some appear to sanctify him, others to demonise him. Through reading about his father, Blair has also learned about his mother. Eileen’s family were successful and well-to-do – her father was the customs and excise chief in Tyneside. As for Eileen, she graduated in English from the University of Oxford. A poet and psychologist, she worked in the censorship department of the Ministry of Information at the beginning of the second world war, then moved to the Ministry of Food and co-wrote scripts for a daily BBC programme called The Kitchen Front.

“She was well educated, quite the equal to my father in terms of intellectual capacity,” Blair says proudly. And then, another explosion. “There’s so much fucking rubbish being churned out, especially from one particular direction. That’s absolute garbage.” I ask what he means. He tells me he is referring to Anna Funder’s book Wifedom, which suggests Eileen was subservient to Orwell and effectively written out of history. He believes Funder took liberties by combining fact with the imagined musings of Eileen and her own thoughts on modern patriarchy.

The problem, he says, is everything has been taken out of context. “I think my mother had decided that my father was the real breadwinner and she would acquiesce, as you did in those days. The mores of the time were that the wife usually fell in with the husband.” Yet he seems to agree with much of what Funder says about his mother being overlooked, and praises Sylvia Topp’s book Eileen: The Making of George Orwell. “I don’t think Eileen did have enough credit. She was sidelined to some extent. What Sylvia has done is taken Eileen and put her at the front of Orwell and put her in proper context.”

Take Animal Farm, he says – Eileen made a huge contribution to it. Some say she came up with the idea. “You can tell that there’s a lot of my mother’s input in Animal Farm, because it’s a completely different book. It’s got a light touch to it. She helped him in structuring the book, I think, and putting the animals in the right context.” Orwell is thought to have got the title for Nineteen Eighty-Four from a poem Eileen wrote called End of the Century, 1984. “She was highly intelligent and had an extraordinary sense of humour, which a lot of people haven’t quite cottoned on to. Very, very funny – you know, the wonderful letter that she wrote to Nora Miles, her friend, in which she said the next letter you get will be a round robin telling everyone I’ve killed my husband.”

That was soon after they got married and were living in a grubby home in Wallington, Hertfordshire. “It was quite a nice little house. It had running water – down all four bloody walls!” He enjoys the joke. “It was pretty rough. And this was for a young lady who was well brought up.” His mother wasn’t used to slumming it. Eileen made no attempt to hide that Orwell could be insufferable – needy, spoilt, impetuous, self-obsessed. But he was also formidably talented, visionary and prolific.

As well as the six novels, there were the three nonfiction books, numerous essays, journals, pamphlets, newspaper articles and poems. Of his father’s writings, what does Blair go to first? “His essays,” he says instantly. “The essays are brilliant. They really are. They’re full of humour.” He cites any number of them: How the Poor Die; A Hanging; Shooting an Elephant; Such, Such Were the Joys. “You can also extract lumps out of books that are stand-alone essays in their own right. In The Road to Wigan Pier, you can take two parts. There’s the description of the tripe shop – after you’ve read that, you’d never eat tripe again. And the other one is the very short essay of the girl poking a stick up a foul drain, which – whether or not it happened, or not in the circumstances in which he wrote it – is a brilliant piece of reportage.”

Does anything make him feel uncomfortable about his father’s work? “Yes. He was very black and white about categorising people. The sandal-wearing, bearded liberal-lefties with sweaters, he didn’t like them at all. And shopkeepers were usually rightwing types.” Does he think Orwell was a snob? “I don’t know. The problem was he spoke with an Old Etonian accent, so that didn’t help, did it? When he went to Spain and was introduced to John McNair, the Tynesider, who was with the Independent Labour party, McNair said: ‘Christ, who’s this bloody tosser?’ Then he found out he’d written Down and Out in Paris and London and Burmese Days and realised who he was. And he goes: ‘Oh, OK!’”

I tell him I was shocked by Orwell’s comments about Jews in Down and Out. “Yessss,” Blair says circumspectly. “Was he antisemitic? From Down and Out in Paris and London, you might say that he was, but I think he was commenting about what other people think of Jews. ‘This is not what I think about a Jew, it is what other people think about Jews and I’m just recording it.’”

To an extent. But certainly not all the time. In Down and Out, he writes: “The shopman was a red-haired Jew, an extraordinarily disagreeable man … it would have been a pleasure to flatten the Jew’s nose if only one could have afforded it.” Jews are so often mean, corrupt, ugly and nasty in Orwell’s work. Later in life, he rowed back on his antisemitism. He despised nazism and declared: “Antisemitism … is simply not the doctrine of a grown-up person,” even if he continued to stereotype Jews in his writing.

The reality is that Orwell was a product of his time, Blair says. He suggests his father was an equal-opportunities offender. “I’m not absolutely certain that he disliked Jews any more than he disliked anybody else. He was a bit anti-Scots for a while. But, towards the end, he was actually quite pro‑Scots. Had he lived for another 20 years, I think there is no question that he would have revised his thoughts on a lot of what he had written, because he was open to criticism and if he was wrong he would say so. You only have to go to his little list, his black book of fellow travellers, that he was asked to do by Celia Kirwan. He later said: ‘You know, some of the people that I criticised I may have been wrong about.’”

The notebook, in which Orwell named 135 suspected communist sympathisers, was handed to his friend Kirwan in 1949, while she was working at the Foreign Office’s semi-secret Information Research Department. It came to light in 2003 and led to Orwell being condemned online as a “reactionary snitch”, a “McCarthyite Weasel” and a “fake socialist”. Does Blair think his father would have regretted compiling the list if he had lived longer? “No, I don’t think so.” After all, says Blair, Orwell thought Stalinism was as great a totalitarian menace as nazism.

But he does think, or at least hope, that his father’s attitude to women would have evolved over time. There are so many examples in Orwell’s correspondence of him making, at best, clumsy or inappropriate passes at women. On occasion, he simply seems to pounce on them. He comes across as predatory, I say to Blair. He nods. “He does, yes. I would like to think his attitude towards women would have changed, because it’s a bit stark.” Some people say he was misogynistic, I add. “I think perhaps he was. He did have a roving eye. He pushed the envelope.” Blair puts a positive spin on it. “He had an open mind and he was able to think beyond the norms of everyday living and behaviour.”

Some women had to push him off, I say. “Well, they did, yes. They had to keep him at bay. The thing is that he liked the company of women who had got a brain, who actually could give him a good argument and could think. He wasn’t going to seduce some bimbo.” He flushes apologetically. “Sorry, I know you’re not allowed to say that, are you?”

Does he think his father’s behaviour would have been tolerated today? “Probably not. ‘Why do you do it, you bloody fool? You’re going to get caught,’” he says, as if addressing his father directly. Is he referring to the affairs and the inappropriate behaviour? “Yeah, I mean, the old adage, thou shalt not be found out.” Or, even better, thou shalt not do it in the first place. “Absolutely. I think I’ve led a reasonably blameless life.”

Eileen threatened to leave Orwell because of his womanising. Blair mentions an occasion, when his parents were living in Marrakech, when Orwell asked Eileen to let him sleep with a young Berber woman as a birthday present. “She said: ‘Yeah, for Christ’s sake, get on with it!’”

If you said to Eleanor you would like to sleep with a young woman as a birthday present, how would it go down? “Well, we’ve been married for 60 years. No, no, I wouldn’t. Christ, I’ve had enough problems with the one I’ve got.” He stops. “I have my tongue firmly in my cheek here.”

The thing is, says Blair, Orwell was complex – and so were his relationships. Many women liked him, for starters. In some ways, Blair believes his father was a romantic. “When he met Eileen for the first time, he said to a friend: ‘That is the woman that I would like to marry.’”

Whatever his shortcomings as a man, Orwell was a literary giant who dedicated his life to exploring the weightiest of subjects – tyranny, war and poverty. Perhaps the most remarkable thing, considering his prodigious output, is that he did so much and wrote so much in so short a life. Does it make Blair reflect on his life? “It doesn’t worry me that I have not achieved what he achieved. I’ve tried to lead a reasonably Christian life and I’m fairly satisfied with what I’ve achieved so far. I was never going to be prime minister, thank God. My father’s outpourings were phenomenal. The wordage that he put out was huge. He used to say that a day not writing was a day lost.”

He brings over the maquette for the photographer. It’s extraordinarily heavy, but Blair carries it with such ease that it could be made of foam. I ask if he sees any similarities between him and his father. “No, I don’t think so. He was a highly intelligent academic. I’m quite the reverse. I was very good at the work I did, but a lot of it was manual. I was a senior demonstrator and ended up in sales training for the tractor people Massey Ferguson. That’s hardly an intellectual occupation.”

Did he ever fancy writing? “No, no, I’m too bloody lazy.” Is it laziness or that his father was a hard act to follow? “Well, I’ve often said that it’s just as well I wasn’t actually DNA-related to him, because everyone would say: ‘Look at your father and look at the rubbish you’re churning out.’ You would always be compared with your father.”

It’s enough for Blair to try to ensure that the Orwell torch continues to burn bright. Not that his father needs much help. I ask what is more important for him, his legacy or his father’s? “My father’s legacy,” he says instantly. “I’m just a keeper – the ordinary son of an extraordinary father.”