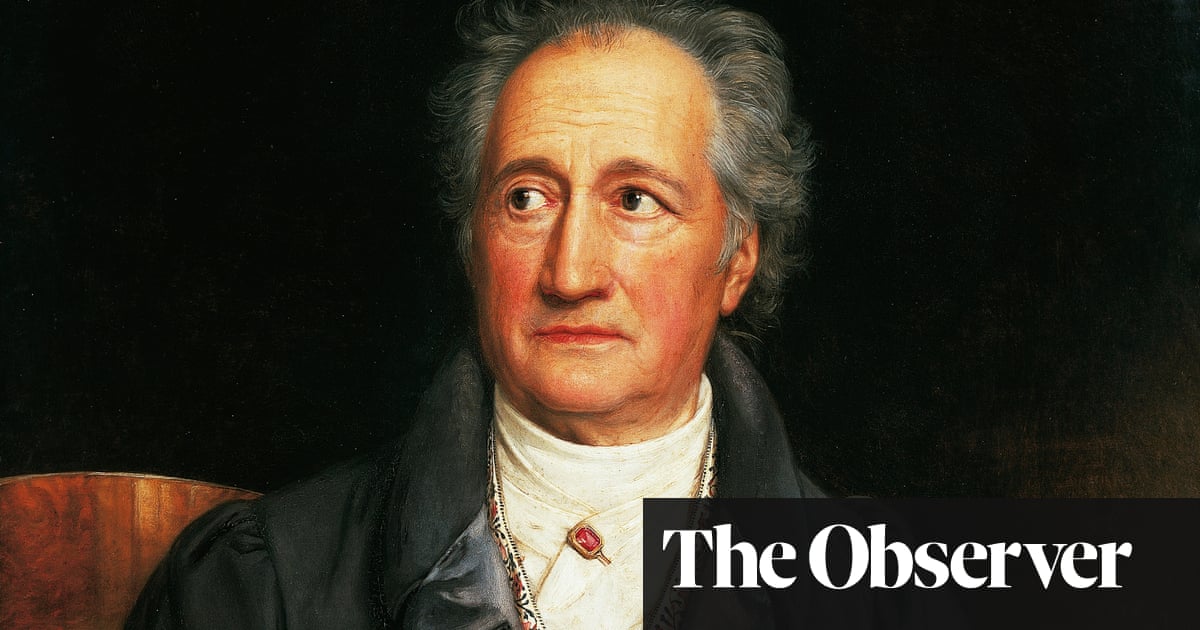

In his 20s, AN Wilson was briefly a candidate for the priesthood. The Anglican God let him down back then, and he has spent the subsequent five decades auditioning substitutes. He now seems to have decided that a deity worthy of worship must be resident in our world rather than afloat above it, and he has therefore erected an altar to Goethe, the sage who “held the German soul in his hands”, established the country’s cultural pre-eminence, and incidentally possessed “the most interesting brain which ever inhabited a human skull”.

Wilson identifies the omniscient Goethe with the hero of Faust, the unstageable poetic drama that was his “whole-life masterpiece”, successively extended and reconceived between 1772 and 1831. In this “philosophical oratorio”, Faust begins as a rebel against Christianity but ends by superseding all established religion. At first he makes a deal with the devil, who prompts him to seduce and cynically abandon a village virgin; at last, evading damnation, he is redeemed by his faith in a benign force that Goethe calls “the Eternal Feminine”, which for Wilson honours the maternal nature that is the source of all life on our abused planet. Although Faust dizzily commutes between heaven and hell, Wilson believes that his exploits tell “the story of us”, exploring the heady but risky freedom we possess in a world no longer policed by God.

Goethe’s Faust appears here as the sovereign spirit of modernity. That’s a slippery notion: Wilson claims that Faust is modern because he is all at once scientifically curious, mystically inclined and sexually itchy, which is a lot to be going on with. Urging his imperial patron to mine the earth, Faust starts as a sponsor of 19th-century capitalism and its ruthless exploitation of nature. Next, early in the 20th century, Faust the erotic fantasist changes into “the forerunner of psychoanalysis”, since nature, as Wilson awkwardly puts it, is “among other things, but primarily among other things, sexuality”. But Faust also awakens the ecological conscience of “all who have confronted the power of nature and its beauty”, and in our own time, after being “tormented by the existential angst of the modern condition”, he still appeals to “those of us who are post- even the post-modern”. As these repetitions suggest, the argument is stretched thin, and over the course of more than two centuries Wilson’s hard-pressed buzzwords deflate like leaky balloons.

Goethe spent his life writing Faust, but his was not really a Faustian life. Though he shared his hero’s sublime aspirations, he satisfied lowlier appetites as well, and Wilson is best when he trains a novelist’s sharp eye on foibles that, as he says in an outburst of spluttering alliteration, were “part and parcel of Goethe’s poetic personality”: his pot-bellied alcoholism, his age-inappropriate crushes and his covert recourse to Roman prostitutes, his snobbery and his taste for pompous interior decor.

Despite such failings, Goethe did possess a global mind, whose contents are unpacked and repackaged in this weighty book, where Persian poets, Hindu prophets and Chinese oracles jostle Plato, Kant and Hegel. My own head, I’m afraid, is not large enough to take in some of Wilson’s murkier explanations: discussing Goethe’s theory of colour, he remarks that “the entoptic apparatus was itself generative, a generativity that depended upon a torsional aspect of turning and returning light”. Could this be one of the aperçus that Wilson says he “culled” – a tell-tale word – from the academic authorities by whom he is bolstered? He concludes with what may be a solemn leg-pull, declaring that Walt Disney’s Fantasia, with “its pink, candyfloss gaudiness and its vulgar sentimentality”, is a truer tribute to Goethe than Thomas Mann’s tragic novel Doctor Faustus.

“A big journey!” sighs Wilson, puffed out as he nears the end. No wonder he sits down to draft one chapter during a meal at an Italian restaurant in Goethe’s home town of Weimar. Despite that pause for refreshment, the universal scope of the survey leads him to overlook petty matters of structure and clarity. The narrative zigzags, and many erratically punctuated sentences don’t parse. Perhaps this negligence is Faustian. At the climax of Goethe’s drama, the striving hero is condemned to death after pausing to review a recent accomplishment: does Wilson take that as a warning not to revise what he has just jotted down?

Even so, I can’t help admiring this act of homage. When Wilson introduces himself as an “absurd and confused reader” who will be “put in his place by a great Master”, his apology reminds me of another legendary idealist – a figure who is less metaphysically reckless than Goethe’s over-reacher, more apt to babble rapturously as he tilts at conceptual windmills. Goethe may be an avatar of Faust, but Wilson, who sets out on a mission that he says is impossible and travels round in circles as he pursues it, is dottily closer to Don Quixote.