Hala Alyan’s lyrical and deeply personal memoir, I’ll Tell You When I’m Home, is about loss, both primordial and immediate. It’s about a marriage falling apart and the birth of a baby via surrogacy after several painful miscarriages. It’s about love in all its messiness, and addiction, and saving yourself at the last possible moment. It’ about displacement, both lived and remembered. An exile that is passed on, etched in your DNA no matter where you go and who you become. It’s about resistance, and understanding that while finding your place in the world might not be the answer, it could be the beginning of healing.

Written in fragments—like memories the author is trying to hold on to before they vanish—Alyan’s memoir tells the story of her life and the legacy of her family, framed by nine months of waiting as her child grows in another woman’s womb. If Scheherazade tells stories to save herself one night at a time, Alyan tells hers not because she dreads death, but because she once did. Because when you come from a land devastated by killing and loss, you cannot help but think about how to ward off death just as you’re affirming life in all its pain and glory.

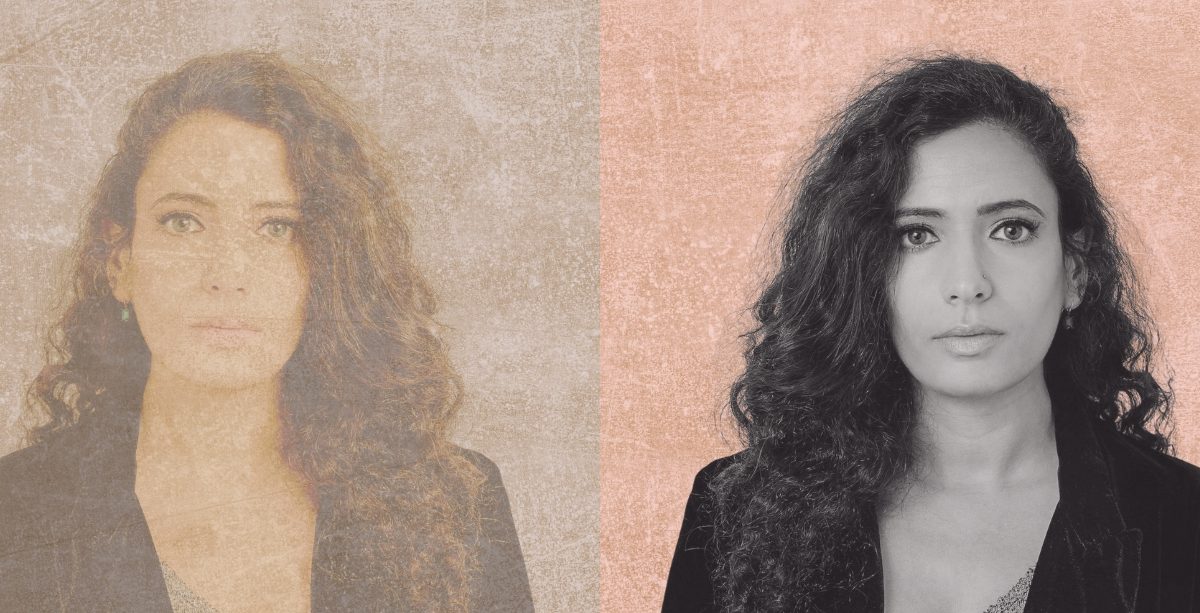

We spoke over Zoom about storytelling as survival, the power of untold stories, and what it means to be a spokesperson for trauma unfolding thousands of miles away.

*

Sahar Delijani: When I texted you that I’d started reading the book, you replied, “Welcome to my mind,” which I found striking—because the memoir doesn’t focus so much on the events themselves as it is does on their impact on you and those around you. It reads like a memoir of the aftermaths. Could you tell me more about when you started writing it and what that process was like? It all just feels so fresh.

Hala Alyan: Yes, you’re right. It is fresh. I was writing a lot of this as it was happening, or right after it had happened. Which of course is not what we usually recommend when we teach creative writing. We always tell students: you have to sit with something, let it percolate. But this was kind of the opposite. I sold this book as a collection of essays on a partial soon after COVID—almost five years ago now. As I began piecing the essays together, my editor kept insisting that we needed more. I distinctly remember the word “connective tissue.” We had to find a way to weave them together.

The process was mostly her taking me by the hand and gently guiding me towards something more memoiristic. At some point she said: I think you’re not writing about your life because you assume we, the reader, already know it, or you don’t think it’s interesting enough. But actually, it feels like you’re writing around things. Can you just tell us the story?

That unlocked the structure of the book. And once that clicked into place, it gave me something solid to hold on to, something I could use to tell the story.

SD: Was the fragmented nature of the book something that emerged as you were writing?

HA: I think it was fragmented because life was fragmented—because it was still happening. I was still in the middle of the fall. It’s shocking that the structure ended up working at all, because so much of it was me processing things in real time, as they unfolded. If I were to write this five years from now, it would be a completely different book—not just because the facts on the ground would have changed, or because I know things about my life and marriage that I didn’t know then. It would also be structurally different. I would have had time to digest it. With this book, I didn’t.

SD: Something that really struck me was this bursting youth in the book—vibrant, obsessive, resistant, angry. But alongside that, an instinct to protect not just the people you love but also those who have hurt you. You even write: After so many years, I’m still trying to protect. So, my question is: how to write and protect? How to write and love?

HA: I would even add to that: how to commit yourself to truth? You hope your readers will approach the book in good faith. And this is not just about abstract readers. It’s the actual people you’re writing about—many of whom you still actively love. You’re constantly aware that the reader doesn’t know their full context, and you feel a responsibility to bring that in.

I’ve come to believe that understanding someone is the greatest act of care we can offer.

Then there’s the broader issue of bad faith readership—cultural projections, assumptions, biases. For instance, a significant part of this book is about an Arab man who causes real harm. And I was deeply aware of how Arab men are already vilified, torn down and made to be antagonists in so much of our cultural and political discourse. So, the question became: how to tell this story truthfully without reinforcing the same narratives?

For me, the instinct to protect something shows up in obfuscation or omission, yes, but more often it emerges through context. I find myself giving more detail than might be necessary from a narrative or literary standpoint—because that’s how I know how to protect. I’ve come to believe that understanding someone is the greatest act of care we can offer. Not love, not forgiveness, not even sympathy—but comprehension. My attempt, always, is try to do that for everyone I write about.

SD: When we write about personal things—whether memoir or fiction based on real experiences—some truths feel easier to say publicly than privately. As if once it’s out there, you no longer have to keep explaining yourself. Here it is. Now everyone knows. Did you feel something similar when writing this memoir?

HA: There’s a lot in this book about sexual violence, the threat of violence, actual violence. There’s a lot about addiction. So yes, I know exactly what you mean. There was this strange sense that it was actually easier to just say it outright, in all its messiness and sloppiness. I’ve never been one for moderation anyway. So, in some ways, it felt more natural to lean into all of the parts of myself I find ugly, complicated, messy—parts that have caused harm and been harmed—than to tell only a little. But truth can also become a little bit addictive, right? The more I told, the more I wanted to tell. And in that way, it actually became easier to just commit fully rather than inch around it.

SD: There’s a recurring sense in the book that when something terrible is happening, you’re already telling yourself: this will be a story later. As if the act of turning that experience into a story becomes kind of a salvation. And I wonder, what about the untold stories? Do you think they can save us too?

HA: I do think there is something powerful in knowing that you have held something, and you’re the only one who knows about it. Like a secret. Some things are so precious, they must be given away, and some things are so precious, they can’t be. There are so many stories that didn’t end up in this book—stories that will never be shared. They just can’t be. And I think there’s a gift and a preciousness in that too. In knowing that some things belong only to you and the people who once told them to you.

SD: This book is about loss, where the historical becomes inseparable from the personal. The loss of land tied to loss of pregnancy, body weight, friends, family. As I read, I kept wondering: is there an original loss, like the original sin, that begets all the others?

HA: I think the original loss in a particular person’s life may not have even happened in their lifetime. There’s something that’s been carried on generationally in my lineage, particularly for the past few generations, which has completely dictated everything: where people live, how people love, what kind of educations they receive, what kind of jobs, what kind of livelihood, whether they live or die.

I feel very strange about being a spokesperson for anything. I’m barely a spokesperson for myself. Half the time, I don’t even think I know what I need in my own life.

And I don’t think you can overstate the importance of that. I come from people who have been forcibly displaced, not once but twice, sometimes three times. So yes, there’s an original loss, maybe that’s it. That rupture from land, from belonging. And I think it’s no coincidence that I feel disconnected from land—I’ve lived most of my life in cities—or that I often feel dissociated from my body. That kind of dislocation echoes through everything.

SD: In the book remembering and forgetting feel like part of the same process—as if you forget to remember and remember to forget. And then, there’s real forgetting: the blackouts, the complete blanks, where you don’t just forget—you truly don’t know what happened, as if you never lived it. But it also feels like you’re not remembering just for the sake of memory—you’re remembering to save yourself. Remembering as rescue.

HA: The stakes of the remembering, for me, are your life. It becomes the work of a lifetime. It’s figuring out who you are, who you can be to yourself, to others. I still remember the stakes of blackouts so vividly—that feeling of waking up and not knowing quite what I’d done, or to whom, and whether I owed someone an apology. As dislocating as that experience was, it also felt quite familiar, which is probably why I kept doing it. And now being sober, I look back and ask: what does that actually remind me of today? And I think it’s probably writing—this idea of fumbling in the dark, trying to piece things together, to make sense of them, to figure out where you need to make amends, where to create coherence. I stopped blacking out. But I didn’t stop trying to put it together.

SD: There are also moments in the book—like when you’re with your grandmother—where you ask questions then forget the answers. Or you want to ask more but feel guilty, like it’s greedy to want to know too much. So, there’s this sense of trying to remember without fully knowing what you’re trying to remember—what you’re trying to lay claim to.

HA: Yes, and that feels very much like the blackouts. It’s the same kind of absence. And it’s also exactly what exile feels like. What you’re describing is the diasporic experience: being severed from a place, from a history, and then trying to make sense of that disconnection. Then the deeper question becomes: how much can you really claim? How much does any of it truly belong to you?

SD: I’d love to hear your thoughts on diaspora. To me, diaspora often feels like an artificial country—an entity with its own rules, rituals, traditions. It believes it’s connected to a place that’s real, rooted. But what it’s tied to is alive and constantly changing. So often, you find yourself tethered to something that might no longer exist.

In an ideal world, I believe, people speak for themselves. People have voices. There’s no such thing as voiceless people. Only people whose voices are interrupted or muted or muffled or denied access.

HA: And there’s nothing more devastating than that, right? When you realize what you’ve built your emotional life on is nostalgia. Meanwhile, the people there have been living, evolving, surviving. I remember being deeply humbled by this in the context of Lebanon. I had all this longing, all this poeticized memory of the place. And then, especially in the past several years, friends who stayed say: Honestly, this is kind of insulting—the way people keep talking about Lebanon from afar. We’re trying to survive here. And you’re all sitting there writing poems about bougainvillea.

SD: They’re saying: We exist. We’re not just a memory. We’re not a concept.

HA: Exactly. We don’t just exist in your imagination.

SD: But at the same time, so often our voice—the diasporic voice—becomes the only one that gets heard. Our version of the truth becomes the truth, even if it comes with an asterisk. And that carries a lot of responsibility, doesn’t it? Having to speak on behalf of something, or someone, far from us to people who know nothing and look to us as their only reference.

HA: I feel very strange about being a spokesperson for anything. I’m barely a spokesperson for myself. Half the time, I don’t even think I know what I need in my own life. So, the idea of being a spokesperson for anyone else is bewildering to me. Maddening even. It’s so far from how I understand the world. It just doesn’t make sense.

And yet, (and I’ve thought about this a lot over the past year and a half, with everything that’s been happening) what then is our responsibility when we’re given a microphone? If we have access to a space that other people don’t have access to? Is it our responsibility to speak into all of those spaces? What does that mean if what we’re really doing is just taking up space? I don’t have a clear answer for any of it.

In an ideal world, I believe, people speak for themselves. People have voices. There’s no such thing as voiceless people. Only people whose voices are interrupted or muted or muffled or denied access. The fact that we become representative of someone isn’t organic—it’s a function of somebody silencing somebody else.

SD: I’d like to ask you about Gaza. I keep returning to this phrase, “Gaza is not a metaphor.” What does this sentence mean to you?

HA: Gaza has become the world’s conscience—which is not something anybody asked for. There’s a way it gets turned into a symbol, a metaphor, a kind of shorthand for all of these things. When, in fact, Gaza is a real place where real people are being slaughtered every hour. This is the project of dehumanization. It’s the counter project. Perhaps the most degrading thing that dehumanization does is that it then positions you in a way where, in order to combat it in any effective way, you have to humanize what was always human and should’ve always been granted that.

SD: And at the same time, where we stand with Gaza says something about us, doesn’t it? There is a moral and political clarity in it. Does it reveal something about us, about our humanity?

HA: At some point, you will be asked what you did with this time. And I don’t even mean that in a metaphysical or spiritual sense. I mean it quite literally—there will be a moment, even if it’s just within yourself, when you’ll have to take stock: How did I show up for this moment?

And the longer this goes, the clearer it becomes what’s happening. I don’t have to do anything except quote people who are doing the slaughtering. You don’t have to believe my words. You can just listen to theirs.

And the question then does become: What are you going to do? What will you be left with when this is over? Who are you going to be? What’s going to be left of you? What will you do with those scraps?

I wrote a book about stories, about the stories we tell to survive. What story are you going to tell about this? Not even about how you look yourself in the mirror. Forget that. What is going to be left of this?

SD: And exactly when it comes to telling stories—to bearing testimony—what happens to our relationship with stories when we realize they can’t stop anything as it’s happening? Is the witnessing still enough when the world keeps burning?

HA: Of course, that’s the question we’re all asking: what is the utility in any of the things we’re doing? I have to believe there is utility—because I can tell you, the only thing worse than continuing to witness and continuing to show up and continuing to try to do something with our spaces, our bodies, our voices—would be not to. That’s the only thing that could be worse than doing it: not doing it.

But what is its value? How is it directly easing suffering and devastation on the ground? That’s a different question. But I have to believe that—and maybe this is how I survive, how those of us that are witnessing diasporically or as allies, survive—that there is value of a witness as something useful, whether that’s today or that’s in five years or that’s in a century.

I believe there is utility in seeing, in not looking away, in keeping the gaze steady. And then writing about it, telling about it, singing about it, attesting to it, giving testimony in formal and informal spaces. I think that’s the value. Because witnessing alone isn’t enough. A witness who does nothing is a useless witness. The value is in what comes after.

SD: This is a book about loss, but, in many ways, it is also about healing. And I wonder if you believe in the possibility of healing? Or is there something else, something other than healing?

HA: I definitely do, but I think the caveats would be that we have to get more flexible with our definition of what it means to heal. People often equate healing with ease, with no longer suffering. Or they equate healing with something being fully resolved. And I think healing—both the process and its outcome—can be really messy and non-linear, and the destination, if there is one, may not look the way you hoped it would. Who you are on the other side of that process may not be as gratifying or simple or clear as you’d hoped it to be. We’re changed by what we go through, not least of all pain and suffering. We’re transformed by it.

So, if healing means reverting back to how things were before, no, I don’t believe in that. But if it means learning how to carry what’s happened, how to live with it, how to keep moving while holding all of it—then yes, absolutely, I do believe in healing.

________________________________

Hala Alyan’s memoir, I’ll Tell You When I’m Home, is available now.