When working on a book about tech, the longue durée of the writing and publishing process is the yawning gulf beneath the tightrope, as the writer makes their way from thesis to destination. A single misstep and, suddenly, irrelevance has swallowed you whole. Your points are obsolete, your ideas outdated. We’ve all moved on.

Article continues after advertisement

But there’s another side to this, especially in this hyper-charged, overheated, shiny-red-ball era of “innovation.” Call it “I’m old enough to remember” syndrome. I’m old enough to remember the “pivot to video.” I’m old enough to remember NFTs. The Metaverse. Soon enough, we’ll all be able to say “I’m old enough to remember the mass psychogenic illness that was AI hype.” To write about tech these days is to witness the birth of stars. It is also to watch just how swiftly they implode.

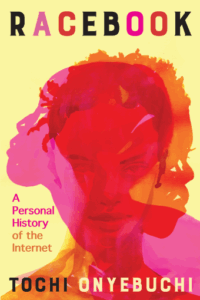

Many of the essays in my essay collection, Racebook: A Personal History of the Internet, were written in 2023, several of them even earlier than that. While I had 2024 to work on them, update the references, try my damnedest to remain au courant, the book is ultimately frozen in amber. How swiftly a book migrates from the Current Affairs section of a bookstore to History.

None of this is new. None of the panic, none of the prophetism.

But what are we really talking about when we talk about tech? Are we talking about the very human need for connection, to brush one’s soul against another’s, however briefly? Are we talking about the pain, the potential derangement, that can set in should we go too long without that? Are we talking about nukes, about holding in our hands the power to do untold damage? Are we talking about being able to walk the streets with a combination of cancer and crack cocaine in your back pocket? Are we talking about magic and our propensity for wonder? When we talk about tech, are we talking about parlor tricks? Are we talking about God?

When writing Racebook, to keep at bay the fear that nothing I wrote would resonate by the time the book hit shelves, I would remind myself periodically that the above was really what I was writing about. I didn’t have to name OpenAI in that essay about androids and the pornographic gaze, because Ovid back in 8 CE already had Pygmalion kissing and fondling an ivory sculpture of his own.

None of this is new. None of the panic, none of the prophetism. Okay, so our cigarettes tell the time and more and more people in a porno are computer-generated. The kids can’t spell and the world leaders are senile. It’s always been falling apart, even when it looked like it wasn’t. Take a long enough view of things and see how little has changed, even as everything has changed. What does Generative AI threaten that wasn’t already under siege?

The lie I hear spoken by every image-generation or video-generation or text-generating Gen AI app is the lie of instantaneity. That the most important thing is having produced. Not the living that precedes the act of art-making, not the living that occurs during the art-making itself. The app will tell you that the most important thing is how fast you made this song that you can get Spotify to pay you for.

You, singular. Without a keyboardist or a drummer or a singer or a mixing engineer, nobody else on payroll, no bandmates. No friends. The most important thing is how fast you did it all, because the second most important thing is that now you can sell the thing you made. Self-published gibberish on the Amazon marketplace, a Surrealist cat video YouTube short, bland country twang for a music streaming service.

You in your bedroom—yes, you—leaning forward hungrily in your gaming chair, can get rich quick and fool yourself into thinking you’ve lived a meaningful life for the cost of a monthly subscription.

Scheming and lazy, you don’t create the Velvet Sundown to win a Grammy or the adulation of your peers or any sense of satisfaction at having done a difficult thing well. You do it to make a quick buck. You don’t do it because the music is compelling or even good. You do it because it’s easy. Because it took no time at all.

Thank God that, during the course of making a single piece of art, I have the chance to grow up, to get older, wiser (insh’Allah), that I have the chance to live.

At bottom, that’s the thing that grinds my gears. “You don’t have to be good at your job anymore,” is what it boils down to. Whether that job is novelist, whether it’s film editor, whether it’s actuary. And it sucks because getting good at the thing is kind of the point. The time, the energy investment—sweat equity, I think the bloodless call it—the care, the education you went and got or the education you went and gave yourself, who will tell the tech evangelists that that’s part of the bargain? That it’s not just tax, it’s reward in and of itself?

Tony Iommi loses the tips of two of his right-hand fingers in a factory accident, but then he makes these two thimbles to replace his missing fingertips and he detunes his guitar to make it easier to play the strings, and suddenly, Black Sabbath has revolutionized music by birthing heavy metal. Human accident, what happens if you optimize that away? What happens if you’re always aiming yourself at right answers? What if you don’t even have to travel a single step to get there?

Thank God it takes me so long to write books. Thank God that, during the course of making a single piece of art, I have the chance to grow up, to get older, wiser (insh’Allah), that I have the chance to live. I’m pretty sure the books are better for it.

Slow down. Take your time. And watch the people urging you to walk faster eventually run out of road. The bubble’s going to burst. It’s math. It’s thermodynamics. None of the AI companies (startups, money laundering operations) are anywhere approaching profitability. NVIDIA GPUs in AI data centers last about as long as Liz Truss’s premiership before burning out. But we’ll still be here. And while the memes will have changed, the fundamental fact of human experience won’t. Which is What We Talk About When We Talk About Tech.

These tech evangelists think they’re dictating the Gospel of Luke when, really, all we hear is the Book of Revelations.

So much harm feels and is so immediate right now. Fascistic creep bubbles like lava through the crevices of America’s political and cultural substrata. A Silicon Valley impetus toward peak optimization—efficiency above all else—pervades, like rhinovirus particles, every aspect of our lives. “Move fast and break things” leaves no time to repair what’s been shattered because it has already moved on to defenestrating some other public good or source of private solace.

Generative AI’s promise of instantaneity is Mephistopheles offering us syphilis. These tech evangelists think they’re dictating the Gospel of Luke when, really, all we hear is the Book of Revelations. Getting the thing—the novel, the song, the movie—right now, as art-maker or as art-consumer, means automating the loveliest parts of the artistic experience. Isn’t it telling how much these false prophets have struggled to sell us on such a vision?

I’m old enough to remember when they thought they could get away with it.

__________________________________

Racebook: A Personal History of the Internet by Tochi Onyebuchi is available from Roxane Gay Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.