His Job at the Fulfillment Center Will Empty His Soul

Fulfillment by Lee Cole

Everyone was given a path. There were shifters and sweepers, sorters and feeders. There were pickers and porters and air drivers. There were loaders and unloaders, ramp workers and water spiders, grounders and stowers and freighters.

Emmett was declared an unloader. Third shift, where they always “needed bodies.” He signed the paperwork, wrote the word “VOID” on a check.

The woman who gave his interview said there were levels to every path, opportunities for advancement, for greater benefits. She made it sound like a game you could win.

Nothing’s binding, she said. People bounce around, find their niche.

Emmett came to realize, as she spoke, that your path meant nothing, really, except the position where you started. It was only a piece of jargon.

I don’t have a permanent address at the moment, he told her. But I will soon.

That’s fine, she said. You’re not alone.

There was nothing but farmland where they built it, and it rose up now from the fields of dead corn like a vast anomaly. A dozen warehouses, two runways. A parking lot fit for a stadium. It looked, from the window of the shuttle bus at night, like a lonesome galaxy in the borderless dark. The sodium lamps in the lot gave off orange coronas, and the fainter beacons of the taxiways arranged themselves in trembling constellations.

The people on board the shuttle were too visible in the harsh light, the shapes of their skulls apparent in their faces. They tightened the Velcro straps of back braces, ate strong-smelling soups and curries from Tupperware, struggling to reach their mouths with their spoons as the bus shook and jounced. They watched porn on their phones—slack-faced, mouths ajar. They played word games, poker, Candy Crush. They spun the reels of cartoon slot machines. They rubbed at scratch-offs with pennies. They stared with glassy resignation at absolutely nothing.

The guard shack was chaotic, men with wands shouting over the high-pitched keening of the metal detectors, herding the workers. The guards were not TSA, belonging instead to a private security firm, and they looked to Emmett like Neo-Nazis who’d recently finished prison sentences—Viking braids, bleached goatees, tattoos of Iron Crosses on their forearms.

He sat with the other recruits in an office annex, listening to Scott, their “Learning Ambassador,” break down the workers’ basic duties and the company’s expectations. He was a small and energetic man, pacing to and fro, his lanyard ID badge swinging pendulum-like. Broken blood vessels lent his cheeks a rosy appearance, and he had a little boy’s haircut, his bangs clipped short in a perfectly straight line.

You might think of this place as a warehouse, he said. But here at Tempo, we like to think of it as a ware-home.

They were made to click through a series of training modules on computers from the early aughts. They watched video clips, wherein a softspoken female narrator highlighted recent company achievements over a soundtrack of jazzy Muzak. The clips underscored Tempo’s ethical commitment to creating a better world. But if Emmett learned anything from them, it was the extent to which the company’s maneuverings had touched all realms of commerce. They were in the business of both fulfillment and distribution, shipping their own parcels—the orders boxed and sorted at smaller regional hubs—along with the parcels of anyone willing to pay. They’d begun to build retail warehouses, in competition with Walmart and Target. They’d been buying regional supermarket chains, and would use their network of distribution centers and their fleet of trucks to deliver groceries directly to the doorsteps of eager customers. In the video, a Tempo delivery driver in her familiar evergreen uniform handed a paper sack of bananas and grapes and baguettes to an elderly woman, who smiled and waved as the green electric truck pulled away.

Officially, it was called the Tempo Air Cargo Distribution Center, but Scott called it simply “the Center.” It was Tempo’s largest distribution hub, and had been built here in Nowheresville, Kentucky, because of its geographic centrality. Some of the workers commuted from Bowling Green or Elizabethtown, but most came from the forgotten hamlets of the surrounding counties, places with names like Horse Branch and Sunfish, Spring Lick and Falls of Rough. There had once been coal mines and tobacco stemmeries in that area, auto plants and grist mills. But all those enterprises had fled or shuttered. Now Tempo had arrived to take their place.

What we’re doing here is regional rejuvenation, Scott said. We’re creating long-term opportunities.

The recruits were called upon to introduce themselves and offer a “fun fact” about their lives. When Emmett’s turn arrived, he said he spent his free time writing screenplays. Really, there’d been only one screenplay—an evolving, never-ending autobiographical work that he’d abandoned and revived a dozen times. But he feared that admitting this would make him sound insane.

How bout that, Scott said. We have a screenwriter in our midst. What are they about?

Just my life, he said. They’re autobiographical.

Hey, I better look out, Scott said. Maybe one day you’ll write about this. Maybe one day we’ll see it on the big screen.

Then he called on the next recruit, whose “fun fact” was that a miniature horse had kicked him in the head as a young boy, leaving him without a sense of smell.

Emmett moved to the warehouse—the ware-home, rather—and began what Scott called the “Skill Lab” portion of training. An enormous digital clock hung near the entrance, red numerals burning through the haze of warehouse dust. Beneath it, a scanner and a flatscreen monitor were mounted. You held your badge to the criss-cross of lasers, and when the system read the barcode, your image appeared on the screen. They’d taken the photos on the first day of orientation, the trainees backed against a blank wall, unsure whether to smile. They looked like mugshots. When you saw yourself appear onscreen—the past-self who’d taken this job, who’d embarked on this path—and you gazed up at the red digits, measuring time by the second, you knew, unmistakably, that you were on the clock. It was the only clock, as far as Emmett knew, in the warehouse.

On the wall, near the break room door, a large sign read: WE’VE WORKED 86 DAYS WITHOUT A LOST TIME ACCIDENT! The number was a digital counter. Emmett wondered what had happened 86 days ago. Each night, the number rose—87, 88, 89—and whatever had caused this loss of time receded further into the Center’s collective memory.

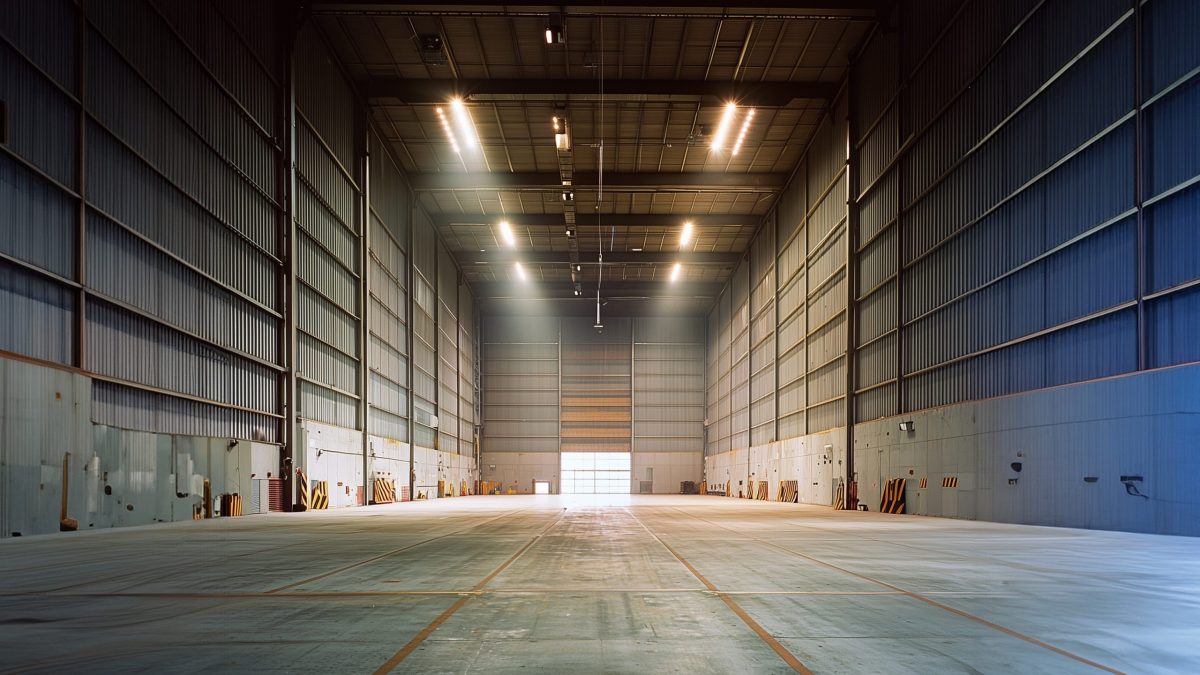

It was a huge, hangar-like structure, an intricate maze of conveyor belts, all churning and chugging at once. The racket was like a subway train perpetually arriving at the platform—the clattering rhythm, the screak of friction. Bays for trucks took up one side; on the other: loading docks for planes. The floor was studded with steel ball bearings and rollers, so the shipping containers—”cans”—could be towed easily from the docks to the belt lanes. It was all so labyrinthine and vast that Emmett felt what he might begrudgingly call awe. He’d never gazed at the vaulted ceiling of a cathedral, sunlight turned to scattered jewels by stained glass, but he imagined the feeling might be similar.

When it came to the work itself, there was not much to learn. If they remembered nothing else, said Scott, they should remember the Eight Rules of Lifting and Lowering.

Approach the object, feet shoulder width apart, bend at the knees, test the weight of the package, grip opposite corners, lift smoothly, pivot or step without twisting, use existing equipment.

Unloading the containers of air cargo onto conveyor belts was the one and only dimension of his work, the same task repeated, ad infinitum. They showed him how to latch the cans into the lanes, how to break the yellow plastic seals. They showed him the little hydraulic knob that lifted and lowered the conveyor belt. (This was the “existing equipment” mentioned in the last of the Eight Rules.) They showed him the “small-sort” belt for loose envelopes and small parcels, and the “irreg” belt for unboxed freight—tires, axles, machine parts, etc.

And that was it.

It’s a simple job, really, said Scott. Put boxes onto a conveyor belt until the can is empty, then bring over a new can. Do the same thing. Rinse and repeat.

Most nights, as he left, he saw the Blood Bus—an RV outfitted by the Red Cross to function as a mobile blood donation center. A fat man stood outside, calling out to the workers as they spilled from the shuttles. Hop on the bus, give your blood to us! he shouted. Hop on the bus, give your blood to us!

The man was always slick with sweat, his face purple and gorged from the exertion of shouting. No one ever seemed to enter the bus, and Emmett wondered why they came here. The last thing he’d want to do, leaving his shift hungry and aching, was donate blood. But there must be a few, he thought, to make the blood man’s efforts worthwhile. Those who heard the call and said, What the hell? They were already spent. Why not open their veins, give a little more?

He met his supervisor, a man named Jason Flake. Everyone called him “Flaky.” He was younger and much taller than Emmett, his arms too long and skinny for his frame. He reminded Emmett of a praying mantis. You could tell the supervisors from the union workers by the clothes they wore—Tempo golf shirts tucked into pleated khakis—and by their radios, shoulder mics clipped to their collars. In the beginning, Flaky kept a close eye on Emmett. Turn your badge to face out, bud, he’d say, and Emmett would rotate the laminated ID badge Velcroed to his upper bicep. They were supposed to unload twenty boxes per minute, and the supervisors knew the precise average of each package handler. The boxes placed on the conveyor passed through a bright, mirrored scanner, each barcode logged in the system.

You’re at 18.3 per minute, bud, Flaky would say, without looking up from his iPad. Try to pick it up a little.

Each night, as his shift wound down, Flaky came to Emmett’s lane, stood in the doorway of the can, and asked him to recite the Eight Rules of Lifting and Lowering. When Emmett had gone through them, Flaky would scribble something on a clipboard and ask Emmett to sign. He came to realize, gradually, that the Eight Rules were an insurance policy; this is why they mattered so much to management. All the other safety protocols—hazmat handling procedures, what to do during a tornado, etc.—would so rarely come to any use that their presence in the modules was almost a formality.

But the Eight Rules—they governed the only sanctioned movement of Emmett’s body on the clock. And if you understood the Eight Rules—if, in fact, you signed your name to a piece of paper attesting that you understood them—then you could never be injured in such a way that blame fell on the company. If you ruptured a disk in your back, or blew out your knee, or crushed your fingers, it would be because you’d failed, in some way, to follow the Eight Rules.

There was a village within walking distance from the shuttle pickup—an “unincorporated community” called Middle Junction with a motel. This was where he’d been living, paying a weekly rate. He’d lived in New Orleans before, had lost his job there at an Outback Steakhouse, and come home to Kentucky knowing that Tempo would hire anyone. He had not yet told his mother, Kathy, he was back. But his money had nearly run out; the motel life was not sustainable. He called her after six months of near silence, sprawled out on the bed’s pilled comforter in the tiny room that stank of cigarette smoke.

I’m home, he said.

Emmett? she said. Are you okay? Where are you?

I’m home, he said again.

In Paducah?

No, I’m in this nowhere town—out past Beaver Dam.

What in the world are you doing there?

Getting a job, he said. At the Tempo hub. I’m almost through with orientation.

What happened to New Orleans?

It’s a long story.

Where are you living?

In a motel.

Well, that won’t do, she said. That won’t do at all.

She made him promise to come home, said she’d buy him a Greyhound ticket. I’d fetch you myself, she said, but your brother and his wife are coming this weekend.

Joel was Emmett’s half-brother, but Kathy never made the distinction. He lived in New York, where he taught “cultural studies” at a small college—a subject Emmett had never been able to make heads or tails of. He’d published a book a couple years earlier and had married his wife, Alice, right after. The last time he’d seen them was at their wedding.

I don’t know, he said. Spending time with Joel had a way of making him feel sorry for the state of his life.

This is a blessing! Kathy said. Both my boys home—we’ll have a family reunion!

The next day, he waited for the bus as twilight fell. The town was little more than a crossroads: a gas station, a farm supply store, a Dollar General with Amish buggies in the lot. Beside the Greyhound stop, in a patch of grass, someone had put up three flagpoles and a gazebo, and there were white wooden crosses in rows, bearing the names of locals who’d died during the pandemic. Emmett waited alone, reading the names, hearing the rasp of wind in the dry corn, the faint melodies of country music drifting from the vacant gas station.

The bus arrived and took him west. He drew a book from his backpack, a manual on screenwriting. It was called The Eternal Story: Screenwriting Made Simple. He read for a while by the light of the overhead lamp till he grew tired. Tinny music came from the other passengers’ headphones. When he closed his eyes, his dreams for the future played like movies. New York, Los Angeles—he’d never seen them in person, only in images on screens.

Traveling by Greyhound had a way of inflicting realism on even the most ardent dreamer.

He watched the scrolling world and thought about his life, how he’d gotten to this point. The Center. One thing he was sure of: they were far from the center. One saw this, clearly, from the window of a Greyhound bus. One saw the brushstrokes of irrelevance in the landscape itself. The rhyme of towns, the patchwork fields. The illusion of movement. Most of America was like this, though Emmett sometimes forgot, spending so much of his life in fantasy. Traveling by Greyhound had a way of inflicting realism on even the most ardent dreamer. One saw, as Emmett saw now, the glowing corporate emblems, the names and symbols hoisted on stilts. One saw prisons that looked like high schools. High schools that looked like prisons. One saw the blaze of stadium lights above the tree line, heard the faint echo of the anthem, of military brass and drums. One saw the salvage yards of broken machines. The mannequin of Christ pinned to a cross. The moon-eyed cattle, standing in smoky pastures at dusk. One saw huge flags rippling above car dealerships. Combines blinking in fields at night. One could see all this, unreeling frame by frame, and understand, as Emmett understood, the immense bitterness of exile.

His mother greeted him at the Greyhound depot. Kathy was a small, sinewy woman, her hair in a silver bob that grazed her chin. The back of her Town & Country minivan was heaped with clothing.

Don’t mind that, she said. That’s all going to consignment.

She hugged Emmett and pulled back to get a good look at him.

The prodigal son returns, she said. You look tired.

I’ve been on the night shift all week.

Your eyes—you look like a raccoon.

It’s good to see you, too, Emmett said.

Kathy lived in West Paducah, between the mall and the old uranium enrichment plant. Much of the farmland there had been subdivided. What had once been tobacco and soybeans was now crowded with lookalike homes and sun-parched lawns, where not even the constant chittering of sprinklers could keep the grass from browning in summer. There was a billboard above I-24—MCCRACKEN COUNTY DREAM HOMES, with a number you could call. This is what Kathy had, a vinyl-sided prefab, much like all the others on the street. They delivered your Dream Home to you in pieces, fitted them together, and then you had a place to live. There were thousands going up like that in Kentucky, more respectable than a mobile home, if only slightly. MAKE YOUR DREAMS COME TRUE, said the billboard, and that’s what everyone seemed to think they were doing. Their dreams were readymade and easy to assemble. They cost very little and were worth almost nothing when you were done with them.

She let him sleep in the next day. He woke at noon and sat at the kitchen table, drinking coffee left over from breakfast he’d warmed in the microwave. Kathy fixed a cup for herself and sat with him. They looked out the sliding glass doors at the backyard. Though it was only August, the walnut trees over the patio had begun to drop their fruit, green husks the size of tennis balls thudding against the cement, some already black and rotting, some floating like buoys in her tiny koi pond. He was glad to see his mother, to be here in the Dream Home, even if it signified another defeat in his life.

So, Tempo, she said. They pay good?

Not really.

Benefits?

Emmett nodded.

Do you miss New Orleans?

The answer was complicated. Though he’d liked New Orleans, he hadn’t really had the money to live in the city itself. He’d lived in Metairie, near I-10, where he’d worked at the Outback Steakhouse. His dream of the French Quarter, of a brightly painted Creole cottage, a banana tree in the backyard, had been just that—a dream. Faraway and unattainable.

It wasn’t a city where I could reach my full potential, he said.

You can reach your full potential working at Tempo?

That’s just to pay rent. What I really want to do is screenwriting.

Like writing movies?

Or a TV show. Whatever.

What happened to becoming a songwriter? Kathy said. That was the last thing you decided you’d be. Before that, it was professional chef. Before that, it was stand-up comedian.

He hated to be reminded of his failed creative pursuits, his veering from one passion to another, but he could always rely on Kathy to bring it up.

Those were naïve goals, Emmett said. I can see that now. But with screenwriting, there are steps. You just follow the steps.

You’re like a kid sometimes, she said. One day, he wants to be an astronaut. The next, a baseball star. The next day, a cowboy.

A screenwriter is hardly the same thing as a cowboy.

Well, I wish you’d go back and finish school.

You can’t major in screenwriting.

You could start with basics at the community college. You could live here.

I plan to live near the Center.

The Center?

Tempo. That’s what they call it.

She made a fretful sound, blew on her coffee, and took a sip. A walnut dropped on the metal roof of the garden shed outside, sounding like a gunshot. They both startled and turned their heads to look.

So what’s Joel coming home for?

He’s doing a lectureship at Murray State, she said. Just for the fall semester, as I understand it.

Are they leaving New York?

It’s up in the air, Kathy said. But Lord, I hope so. I pray every day they don’t get shot or stabbed or blown up.

He’ll never come back to the South.

I have so much to do before they get here, she said, ignoring him. I have to clean the house. I have to fix your brother’s cake.

What cake? Why does he get a cake?

It’s a homecoming cake, she said, as if it should be obvious.

Where’s my homecoming cake?

Well, how was I to know you were coming home? You vanish and reappear. You never call.

Even if you’d known, there would be no cake.

Why shouldn’t I celebrate Joel’s successes? He’s very accomplished. I wish you’d talk to him more. You could ask him for advice, about writing and whatnot.

I don’t need his advice.

Well, can I give you a piece of advice then? she said.

He sighed theatrically. I’m listening.

Write down your goals. Take a sheet of paper, write “My Goals” at the top, then put everything down. That way, you have it as a reference point. You can’t betray yourself. You can’t let yourself off the hook.

Emmett wanted to ask what her goals had been at twenty-eight, if she’d aspired to anything more than raising her children in this town where nothing much happened and no one expected it to. Instead, he said all right, he would write down his goals, and this seemed to satisfy her.

Emmett’s car had broken down in New Orleans. This had precipitated, in part, his decision to leave. His grandmother, Ruth, was too old to drive. She was too old to do anything except watch Fox News. She had a 1997 Mercury Mystique with a lineup of Beanie Babies in the back windshield, and she told Emmett she would sell it to him for a dollar.

Kathy dropped him off, and he found her in the backyard with Lijah, the exterminator. There had been a long-standing issue with groundhogs, her little house abutting a wooded creek where they bred. They gnawed through the lattice surrounding her deck and tunneled beneath the foundation. Lijah was a church friend. She’d been calling him for years to set traps in the woods, snaring rabbits and cats as often as groundhogs. It came to be their habit, over time, that after he’d discharged his official duties, she’d invite him to sit a spell and drink coffee.

She saw Emmett coming and went to greet him. Her hair was dyed coal black, her eyes as small and dark as currants. An intricate crazing of broken blood vessels had turned her nose and cheeks purple.

Lijah’s spraying dope, she said. Lijah, you remember Emmett, my grandson?

Lijah waved. He stood beside her garden shed, holding a sprayer wand attached to a backpack tank, his gray hair tied in a ponytail. His T-shirt said CRITTER KILLERS—the name of his company—though he seemed to be the only killer of critters on the payroll.

The traps were empty, so I’m fixing to spray, he said.

Spray for what? Emmett said.

Lijah shrugged. Anything.

It’s a constant battle, Ruth said. Varmints, termites, snakes. They all try to get inside. Then you’ve got prowlers. Dottie Driscoll down the street caught a prowler in her backyard.

Fraid I can’t spray for that that, ma’am, said Lijah.

What prowler? Emmett said. Who was it?

How should I know? Dottie’s grandson ran them off. He’s a sheriff’s deputy. Her grandchildren visit her every day.

I doubt that.

Emmett is Joel’s brother, Ruth said. I’s just telling Lijah I’ve got me a famous author for a grandson.

I’s just telling Lijah I’ve got me a famous author for a grandson.

I always wanted to write a book, Lijah said, squirting poison along the base of the shed. Problem is, I never liked writing.

That would be a hurdle, Emmett said

When you’re done, I’ll warm us some coffee, Ruth said.

I’ll be covered in dope spray, ma’am. You don’t want me tracking all that in.

Never mind that, Ruth said. I’ll show you my copy of the book.

The smells of her house—her White Diamonds perfume, her geriatric ointments, the jar of congealed bacon grease by the stove—brought Emmett back to the boredom of summer mornings when Ruth would keep them, his mother at work, Joel entertaining himself with the World Book Encyclopedia. The days had seemed so long, his life so long ahead of him.

Down the hallway, in the bedroom, Emmett and Lijah stood before her bookcase. There were three copies of his brother’s book, wrapped in plastic, wedged between Erma Bombeck and Nora Ephron. It was called Going South: The Descent of Rural America. She took one down with great ceremony and placed it like a fragile artifact in Lijah’s open hands.

Going South, he said. Well, I’ll be.

We always knew, didn’t we? Ruth said, squeezing Emmett’s arm. Our Joel was special. He used to recite the presidents. Five years old.

A memory: Joel with his bowl cut and secretive smile, standing on a chair, surrounded by adoring faces and the remnants of Thanksgiving supper. Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison. . . .

He was always reading, Ruth said. And Emmett was always watching movies.

I don’t suppose you became a movie star? Lijah said.

Emmett’s still finding his way, she said. Aren’t you?

Emmett managed to smile.

She returned the book to its place and asked Lijah how a cup of coffee sounded.

I’d never turn it away, he said.

Tell you what, I’ll make a fresh pot.

They’d started to leave when something caught Lijah’s eye. He went to the old laundry chute in the corner and crushed a spider on the wall with his meaty fist.

We’ve got a problem here, he said. He opened the chute door and peered inside.

I never use that thing, Ruth said. It’s been blocked for years. You put something in and you never see it again.

It’s a breeding ground, Lijah said. They love the dark. I’ll spray before I leave.

When Lijah had gone, she led Emmet down to the carport and showed him the Mercury Mystique. The Beanie Babies were still arrayed in the back windshield, their colors sun-faded. Do I get to keep the Beanie Babies? Emmett said.

Oh sure, Ruth said. They were supposed to make me a lot of money but they ain’t worth a cent now.

They sat in the living room after, eating Danish cookies from a tin, dipping them in coffee. Fox News was playing. It was never turned off, only muted. They were interviewing the recipient of a face transplant. The man had been disfigured by an accident, and now he wore the face of a dead man like a mask. It was convincing, though his mouth did not work quite right, and you could see where the sutures had been along his forehead.

Ruth was half-deaf. She leaned forward, straining to hear. They took off his face, she said, and gave him another man’s face?

A dead man, Emmett said.

She bit one of the stale cookies in half and shook her head at the marvel of it. They do everything now, don’t they? she said.

She relayed the latest gossip. He learned who of his cousins was pregnant, who was getting married, who was headed for divorce. She sometimes mixed up the names, but Emmett knew, more or less, who she meant. Once the family gossip had been covered, she moved on to the deaths. Grandma Ruth kept a relentless mental catalogue of all the strange and grisly deaths in McCracken County.

A man in Symsonia got himself killed on a four-wheeler, she said. Two boys drowned at Kentucky Lake last month. Two foreigners shot each other at a bar. Let’s see, what else. Oh! There was the man who caught himself on fire.

He what? Emmett said. When Grandma Ruth said the word “fire,” it was like the word “far,” and it took him a moment to catch the meaning.

Fire, she said. He pulled up at the filling station down the street, covered hisself in gasoline, and lit a match. They showed the footage on the TV.

Jesus. Why’d he do it?

He was protesting.

Protesting what?

She bit another Danish cookie and shrugged. Just life, I guess, she said.

She excused herself to the restroom, and Emmett went down the hall and stood before the shelf that held Joel’s books. He looked at the cover: a caved-in church in a field, the stacks of a coal-fired power plant in the hazy distance. He’d read it a while back, though perhaps it was more accurate to say he’d skimmed. The essays were about Kentucky and the mechanics of what Joel called “rural despair.” The running theme throughout was the privatization of mental health. He used terms like “neoliberal” and “post-Fordist,” the meanings of which Emmett understood only foggily, and argued that depression was not simply a chemical imbalance, but a normal human response to the vulgarity of late capitalism.

The book alternated between abstract theory and a more personal style. One of the essays explored Joel’s relationship with their mother and her spiral into QAnon conspiracy theories. Emmett had always felt it was unfair; it exaggerated her views and made her seem like something, or someone, that she wasn’t. Now Joel had some money and a job. He had his smug-looking photo on the jacket of a book.

In a flush of sudden anger, he took all three copies of Going South from the shelf, opened the laundry chute, and let them tumble from his arms into darkness.

The first place he drove, in his new Mystique, was the Kmart parking lot in Lone Oak. The Kmart was no longer in business, though you could still see the pale impression of the letter K on the stucco where the sign had been. Now it was a place where people bought drugs. The only dealer Emmett knew was a grade school acquaintance called Fuzzy. Hed hit puberty at nine years old and grown a thick pelt of reddish fur on his back and arms. The nickname had followed him ever since.

Fuzzy pulled up in a maroon Buick LeSabre and Emmett got inside.

How you been, Fuzzy? Emmett said.

You know me, bro, he said. Stuntin to keep my grind strong.

On one level, Emmett had no idea what this meant; on another level, he sort of did.

Fuzzy complained about the recent legalization of pot in the state of Illinois. People don’t come to me no more, he said. They go across the river.

He wore a flat-bill cap and a T-shirt that said AFFLICTION with a skull on the front. There were snakes writhing out from the mouth and the eyes of the skull. He was as hairy as he’d ever been.

You wanna hear my latest verse? Fuzzy said.

Sure, Emmett said.

Fuzzy put on a beat, the subwoofer in his trunk so forceful that the sound vibrated deep in Emmett’s bowels. The verse was about no one understanding him, how one day he would prove everyone wrong and release a multiplatinum album. This was all part of the ritual. If you wanted weed from Fuzzy, you had to listen to him rap. Then, when it was over, he would say you were his favorite person.

You’re my favorite person, man, he said. I mean that.

Thanks, Fuzzy.

Fuzzy gave him a quarter ounce of brick-pack weed and said, Hey, love you, homie. Keep that chin up.

Emmett found himself saying, I love you, too, and when the Buick pulled away, he stood absolutely still for a few minutes in the too-bright sun, a warm wind blowing napkins and fast-food trash across the lot.

At home, he found Kathy in a frenzy of preparation—vacuuming, mopping the linoleum, standing on a stepladder to dust the fan blades. Emmett cleaned the toilet and the tub, wearing yellow dish gloves, pausing now and then to drink from a can of beer. It seemed like overkill, but Joel had always been their mother’s favorite—her firstborn, her college graduate. It would not be obvious to anyone from the outside, for they argued fiercely about everything. But this fierceness stood as proof of their bond to Emmett. It was like they desperately wanted to save each other. She wanted to save him from worldly pursuits. He wanted to save her from right-wing politics. And when neither made progress on these fronts, they took it as evidence of insufficient commitment to the war effort, and entrenched themselves further, holding fast to the vain hope of victory.

They were supposed to arrive by suppertime. Kathy made fried chicken, black-eyed peas with ham hock, cornbread in a cast-iron skillet—all of Joel’s favorites. Frying the chicken had been onerous and left the counter dusted with flour, the stovetop spattered with buttermilk and oil. She’d made a hummingbird cake, normally reserved for Joel’s birthday. It was a dense cake with banana and pineapple and layers of cream cheese frosting. Emmett had never had a taste for it. She set the table and displayed it on a cake stand of cut crystal, the engraved patterns in the glass catching sparkles of sunlight.

Is this the only dessert? he said.

Well, yes. It’s Joel’s favorite.

What’s my favorite cake?

She pretended not to have heard this and hurried over to stir a decanter of sweet tea, the wooden spoon clinking against the glass. I’ve got butterflies, she said. My heart’s going a mile a minute.

They’re not foreign dignitaries. It’s your son and his wife.

You’re not helping, she said.

In the guest room, he crumbled the weed on a sheet of notebook paper and put some into a glass bowl. He opened the window, took a hit, and coughed softly. Lawnmowers were buzzing in the distance, the scent of cut grass wafting on the breeze.

Kathy had two lifelong obsessions: Elvis and Hawaii, both of which were reflected in the guest room’s décor. She’d been to Hawaii once with a church group, years ago, and had longed to return ever since. There were carved statuettes of the goddess Pele, velvet paintings of Diamond Head. Glossy shards of volcanic glass in souvenir ashtrays. A poster of the 1961 film Blue Hawaii hung over the bed, Elvis in tiny pink shorts and a pink lei, surrounded by fawning women.

Feeling anxious, wishing to distract himself, he swept the powdery kief from the notebook paper and wrote “My Goals” at the top. He thought for a minute, then jotted down the first few that came to mind. Find apartment, Make money, Pay off debts, Meet someone new. He wrote down, Buy a car, just so he’d have something to mark off. Then he thought for a moment and wrote, Do something creative, something meaningful that will leave a lasting legacy and allow you to face mortality without fear.

Emmett took his old Bible from the bookshelf. It was the copy he’d been given as he entered Youth Group at age twelve. On the cover, a skateboarding kid, mid-kickflip, made the universal gesture of “rock on.” It was called The Bible: For Teens!

He stretched out on the brass bed with The Bible: For Teens!, his bare feet warmed by a square of sunlight, and thumbed through the onionskin pages till he found the parable of the prodigal son. He’d forgotten the prodigal son had asked for his inheritance up front, to spend on prostitutes and wild parties, and had come home penniless. It relieved Emmett to read this, for he had asked for nothing up front. He was not like the prodigal son at all.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.