I have been told that one of the surprising things about my debut novel, This Here Is Love, is its seventeenth-century setting, the joyless beginning of slavery, instead of the nineteenth century, the hopeful abolition of this national shame. Actually, the novel begins nearly seven decades after the 1619 arrival of the first Africans who were pressed into servitude the American colonies. The novel’s touchstone, however, is the possibility of freedom that existed for these compulsory immigrants.

Article continues after advertisement

When I began the research for this article, I was hoping to find two things: enough details to make tangible people out of the “twenty and odd Negroes,” as historical documents often refer to them, who were the first Africans to remain in the British colonies in 1619, and ample evidence of the widely held belief—which I also believed—that those Africans had been treated more like indentured servants than enslaved chattel.

Exploration led me to the wonderful document, “1619: Virginia’s First Africans,” prepared by Beth Austin, Registrar & Historian, of the Hampton History Museum in Hampton, Virginia.

According to the article, while there is a sliver of truth in the belief that those first Africans were treated like indentured servants—a few of them did toil their way to freedom—there is more longing and myth in this statement than anything else.

To begin with, those “twenty and odd Negroes” were most likely thirty or more, and they were a remnant of their original number, three hundred and fifty souls, almost half of which had already perished before their encounter with the English privateers of the White Lion and the Treasurer.

While there is a sliver of truth in the belief that those first Africans were treated like indentured servants—a few of them did toil their way to freedom—there is more longing and myth in this statement than anything else.

By the time those Africans arrived at Point Comfort in what would become the colony of Virginia, they had survived violent kidnapping by Portuguese colonizers and their African henchmen, the Imbangala, who seized them from the Kingdom of Ndongo in modern-day Angola, transport to the Portuguese Fortaleza de Sao Miguel, a wretched middle passage aboard the San Juan Bautista, and the sale of at least twenty-four of their children in Jamaica.

The Africans who waded into the brackish waters of Hampton Harbor, their very bodies traded as payment for “commodities” needed by the crews of the White Lion and the Treasurer, had already been baptized by blood and sorrow into the community of New World enslavement.

However, much of the legislation written in the decades after their arrival tells us there remained slim-chances, skin of the teeth opportunities, and loopholes to freedom and fellowship that had yet to be eradicated, obliterated, sealed-off. Because in the minds of some—not enough, and not just the enslaved—where we ended up, what we became, a country that determined humanity by one arbitrary trait, color, is not where we had to be.

In Virginia, the General Assembly set us upon this path with the 1662 law of Partus Sequitur Ventrum which states,

WHEREAS some doubts have arisen whether children got by any Englishman upon a negro woman should be slave or free, Be it therefore enacted and declared by this present grand assembly, that all children borne in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother, And that if any Christian shall commit fornication with a negro man or woman, he or she so offending shall pay double the fines imposed by the former act.

Beyond the declaration that turns its back on centuries of English common law (by which children inherited their status from their fathers) in order to perpetuate generational enslavement, two things are of interest here: Among whom did those doubts arise? And, accepting the premise that Christian referred only to those immigrants from European countries as stated in the History Museum’s research, who were these Christians who had to be doubly fined to cure them of consorting with their Negro counterparts?

In 1667, further doubts arose as to whether those aforementioned children should be made free by baptism into Christianity. The resounding answer from the Virginia General Assembly was no. The ruling class, now, “freed from this doubt,” could welcome their slaves into the bosom of Christianity without fear of losing their valuable human property. This escape, used by Elizabeth Key Grinstead to sue for freedom in 1656, was effectively blocked.

If the gulfs had been real or impassable, what need then for landowners to legislate the separation of Europeans from people of color?

There were, of course, other doubts and questions. In 1670, the Virginia Assembly was tasked with determining if “Indians or negroes manumitted, or otherwise free” could purchase “Christian servants?” No.

In 1691,

for prevention of that abominable mixture and spurious issue which hereafter may increase in this dominion, as well by negroes, mulattoes, and Indians intermarrying with English, or other white women, as by their unlawful accompanying with one another, it is hereby enacted, that for the time to come, whatsoever English or other white man or woman being free shall intermarry with a negro, mulatto, or Indian man or woman bond or free shall within three months after such marriage be banished and removed from this dominion forever.

Culminating in “An Act Concerning Servants and Slaves,” in 1705, the penalties grow more dire for whites, while the punishments, for Negroes, grow more violent. Those who possess the authority of white skin are allowed, with near impunity, “to dismember” and “to kill and destroy” slaves who resist the unrelenting theft of their autonomy, their labor, their humanity.

The possibilities which animate my stories live right there in the language of seventeenth-century laws. The elites of colonial society had to legislate difference in status, distance in proximity, and the alienation of affections between people of European, African and Indigenous ancestry.

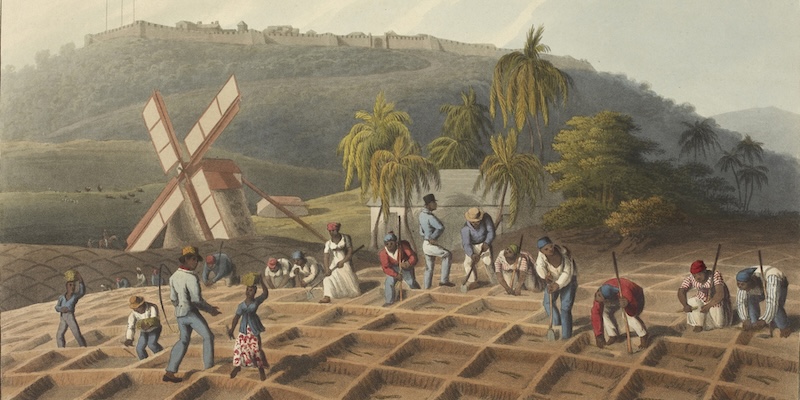

These separations, it would appear, were not necessarily clear or innate to the people who toiled together in a master’s fields. If the gulfs had been real or impassable, what need then for landowners to legislate the separation of Europeans from people of color?

Whereas there are doubts and questions, it is quite possible that my characters Shango, a slave, and Rowan, an indentured Scots-Irishman, would cast their lot together as friends primarily because they sense a commonality in their poverty and in their status as sorrowing exiles.

Whereas there are doubts and questions, This Here Is Love makes clear what is hidden in history, that the enslaved resisted their vile treatment in every way imaginable—from faking illness to breaking tools, from running away to suicide, from insurrection to murder—because they always knew that their lives and labor rightfully belonged in their own capable hands.

Whereas there are doubts and questions, the desperate indentured servants of the colony of Virginia, forged ties, families and alliances with the heavy-hearted Africans who disembarked into the brackish waters of Hampton Harbor, a harbor created by the confluence of the freshwater rivers with the salt of the Atlantic.

Whereas there are doubts and questions, we are supposed to dwell together, humanity flowing into and enriching humanity, and for a brief period of about forty years, we did.

______________________________

This Here Is Love by Princess Joy L. Perry is available via WW Norton.