“Think for a moment what would happen to a race of men whose material inventions placed in their hands unlimited power for destruction before they had developed moral inhibitions sufficient to prevent their using that power to destroy themselves.”

–Pierrepoint B. Noyes, The Pallid Giant (1927)

*Article continues after advertisement

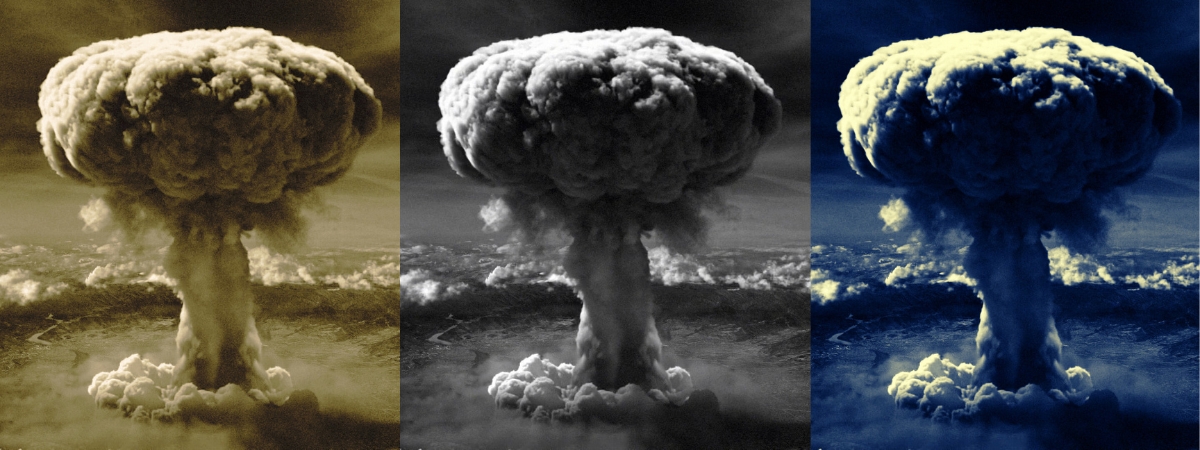

The detonation of an atomic bomb in the sky above Hiroshima, Japan, on 6 August 1945 had the quality of an apocalypse: the violent unveiling of secret knowledge about the universe. For most people it was a true revelation which shook their understanding of how the world operated.

Yet some found the news easier to process. As Philip Wylie, the author of When Worlds Collide, observed, it became commonplace to say that “the only considerable group of Americans who understood what it meant consisted of kids. The kids were held to be those who read science fiction magazines, books and so-called comic books.”

The atomic bomb, or something like it, had been a regular presence in popular entertainment for three decades before the act of imagining it suddenly came to be perceived as a threat to national security. In June 1943, Byron Price, director of the United States Office of Censorship, sent a confidential memorandum to thousands of publications and radio stations, instructing them to avoid any mention of atomic fission, atom smashing, radium, uranium or anything else that might inadvertently point to the fact that tens of thousands of people were secretly engaged in the Manhattan Project, a crash program to design and build an atomic bomb.

But Price failed to consider that in the rapidly proliferating pages of America’s science fiction magazines, the knowledge that a bomb could be built using a uranium isotope was no secret at all. As early as May 1941, Robert Heinlein’s “Solution Unsatisfactory” had described a top-secret project to build a bomb from uranium-235.

The censors were slow to act until Astounding Science Fiction published Cleve Cartmill’s “Deadline” in March 1944. “Have you heard of U-235?” asks one character. “Who hasn’t?” another sniffs.

The atomic bomb, or something like it, had been a regular presence in popular entertainment for three decades before the act of imagining it suddenly came to be perceived as a threat to national security.

Cartmill got the idea from John W. Campbell Jr, the MIT-educated editor of Astounding, a magazine with many avid subscribers inside the Manhattan Project. After “Deadline,” the Army ordered Campbell to publish no more stories on the subject but he countered that readers were by then so accustomed to stories with titles such as “Atomic Fire” and “The Atom Smasher” that their sudden disappearance would raise suspicions.

Children, meanwhile, were already au fait with the devastating power of the atom via the comic-strip adventures of Flash Gordon, Mickey Mouse and Buck Rogers. Created by Philip Francis Nowlan in 1928, Buck’s first adventure, “Armageddon 2419 AD,” dropped the time-torn astronaut into the aftermath of an obliviating war involving “disintegrator rays,” rays being more popular than bombs at the time.

Nowlan’s hero became the most ubiquitous ambassador for the future since H.G. Wells. “The use of atomic energy seems a Buck Rogers idea,” The New York Times reflected in 1944, “but this is a Buck Rogers war.” Even Leslie Groves, the leader of the Manhattan Project, initially thought that the atomic bomb was “a crazy Buck Rogers project.”

Superhero fans were no less familiar with atomic weaponry. In 1944, the FBI forced the postponement of a story in which Superman’s arch-enemy Lex Luthor invents an atomic bomb, yet Batman had already foiled a Japanese spy who used radium to build an “atom disintegrator,” a weapon “more destructive than anything man ever dreamed of.” Though the censors were far too slow to consider fiction, that did nothing to hinder their zeal.

Philip Wylie himself strayed into trouble in 1945 when he wrote a story called “The Paradise Crater,” about the efforts of neo-Nazis in a future 1965 to avenge Hitler’s defeat by building uranium bombs. Wylie fell afoul of Blue Book editor Donald Kennicott’s unusually dutiful decision to seek official permission in advance.

In short order, Kennicott was instructed to bury the story and Wylie was placed under house arrest in a hotel room in Connecticut. What, asked an Army Intelligence major, did Wylie know about the atomic bomb? The major said that he was prepared to take Wylie’s life, and his own, if it was necessary to prevent a security leak.

Wylie protested that he had no inside information, nor did he need any. Thanks to his publicity work for the US Air Force, he had friends in high places and was soon released. He offered to shred the manuscript but the major said, no, he should hang on to it until the war was over.

“The Paradise Crater” did indeed appear in the October 1945 issue of Blue Book, by which time the whole world knew about the atomic bomb. “I saw the headline, brought on the bus by a stranger, and thought: Yes, of course, so it’s here!” recalled one young science fiction writer, Ray Bradbury. “I knew it would come, for I had read about it and thought about it for years.”

Not that there was any cause for the science fiction community to feel smug, because what they had also foreseen, more often than not, was world destruction. “People do not realize civilization, the civilization we have been born into, lived in, and been indoctrinated with, died on July 16 1945 [the date of the first bomb test], and that the Death Notice was published to the world on August 6, 1945,” wrote John Campbell in his first Astounding editorial after Hiroshima. He added, “There is only one appropriate name for the atomic weapon: The Doomsday Bomb.”

The first book in which atomic energy was employed to end the world was published fifty years before Hiroshima: Crack of Doom by the Northern Irish writer Robert Cromie. “No man can say to science ‘thus far and no farther,’” cries the novel’s deranged villain Herbert Brande. “No man ever has been able to do so. No man ever shall!”

Pulling together the 1890s archetypes of the mad scientist (usually foreign) and the anarchist conspiracy, Brande leads a clique of scientists called the Cui Bono Society, which believes that the universe is a hideous blunder which should be remedied by way of “the vast stores of etheric energy locked up in the huge atomic warehouse of this planet.”

He fully embraces his chiliastic role: “I swear by the living god—Science incarnate—that the suffering of the centuries is over, that for this earth and all that it contains, from this night and for ever, Time will be no more!’

Cromie’s novel appeared in 1895, the same year that Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays caused a worldwide frenzy of fascination and speculation. The following year, Henri Becquerel inadvertently discovered that uranium emitted radiation.

In 1897, Rutherford teamed up with an even younger chemist, Frederick Soddy. In 1902, they discovered that radioactivity was produced by the spontaneous disintegration of atoms in certain chemical elements and their transmutation into other elements, and argued that matter should be understood as a colossal storehouse of energy.

Atomic energy came to embody the power of science to elevate humanity or to end it. Soddy publicly expressed the heaven-or-hell implications for the first time: whoever could harness the atom could “make the whole world one smiling Garden of Eden” or “possess a weapon by which he could destroy the Earth if he chose.”

This was mouth-watering fare to H.G. Wells. Having described a planetary collision, a Martian invasion and the death of the Sun, how could he resist a potential world-killer that was so near at hand? Wells dedicated his 1914 novel The World Set Free to Soddy’s work and had a Soddy-like figure explain the science: “We know now that the atom, that once we thought hard and impenetrable, and indivisible and final…is really a reservoir of immense energy.”

In 1933, a scientist named Holsten achieves induced radioactivity and immediately feels “like an imbecile who has presented a box of loaded revolvers to a crèche.” In 1956, Holsten’s discovery finally leads to a world war and produces the first ever appearance of the phrase atomic bomb.

“If there had been no Holsten there would have been some similar man,” writes Wells. “If atomic energy had not come in one year it would have come in another.” There’s no stopping science.

Thirty years before Hiroshima, Wells had no way of knowing how such a weapon might work. He misunderstood the concept of radioactive half-life, so his bombs, made from the fictional element Carolinum, don’t just continue to emit rays indefinitely; they continue to explode.

Nonetheless, there are some strikingly prescient images. The bomb is “a shuddering star of evil splendor” which produces “a great ball of crimson-purple fire like a maddened living thing” and “puffs of luminous, radio-active vapor.” Halfway through the novel, the strangely optimistic title begins to make sense: the “moral shock” of atomic war inspires the survivors to form a world government which controls Carolinum supplies and puts an end to war.

The idea of a weapon so heinous that it would end war wasn’t unusual.

While not a final battle between good and evil, Wells’s “Last War” does fulfill the role of Armageddon, burning a path to peace on earth: “We’ve had unity and collectivism blasted into our brains.” The Spectator skeptically called this “one of his periodic fits of millennial reconstruction. It would be unfair to accept Mr. Wells’s latest vaticinations as final, because he is in the habit of scrapping civilization every two years or so.”

Wells came to accept the criticism. “A disposition to believe in these spontaneous waves of sanity may be one of my besetting weaknesses,” he wryly reflected in 1934.

But the idea of a weapon so heinous that it would end war wasn’t unusual. Earlier future-war stories such as Hollis Godfrey’s 1908 book The Man Who Ended War had advanced the pacifistic case for creating the ultimate deterrent. The inventors of poison gas and the airplane had expressed similar hopes of horrifying the world into peace.

As Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite and father of the eponymous Peace Prize, told the pacifist Bertha von Suttner in 1891, “Perhaps my factories will put an end to war sooner than your congresses: on the day that two army corps can mutually annihilate each other in a second, all civilized nations will surely recoil with horror and disband their troops.”

In a 1921 article called “How to Make War Impossible,” Thomas Edison argued that governments should continue to “produce instruments of death so terrible that presently all men and every nation would well know that war would mean the end of civilization.” But Wells’ contemporary George Griffith had already scotched what the peace activist Norman Cousins mockingly described as “the war-is-now-too-horrible theory” in The Lord of Labour, which he dictated from his deathbed in 1906.

When the German inventor of a disintegrator ray claims that it will “make warfare impossible by making it so awful that no man in his senses would go upon a battlefield,” the Kaiser responds, “My dear Professor, before you make war impossible you will have to make another discovery. You will have to find out how to alter human nature; and that, I venture to say, is beyond the capabilities of even your genius.”

In 1914, Wells’ speculative atomic bomb caused a mighty splash, with even Ernest Rutherford calling it “interesting,” if implausible. For the next thirty years, stories about future wars tended to follow Wells’ lead.

First, an arrogant, short-sighted scientist conceives the basis for a horrendous new superweapon—a bomb, a gas, a virus—without considering the consequences. Then governments, addicted to conflict, use this weapon to wage a world war of unprecedented carnage. Finally, the sickened survivors vow to rebuild a global society dedicated to peace.

Sometimes a scientist uses the mere specter of the superweapon to skip to phase three: in Arthur C. Train and Robert W. Wood’s 1915 novel The Man Who Rocked the Earth, which cites both Wells and Soddy, a scientist called Pax blackmails the world into abolishing war with a uranium-powered ‘Lavender Ray’. Occasionally, though, the superweapon is so efficient that there is no phase three.

What would the crucial element be? While waiting for science to find out, writers had to invent their own.

In Karel Čapek’s 1922 novel Krakatit, the atom-disintegrating explosive that could “blow the boat of humanity to pieces” is named after Krakatoa. In Upton Sinclair’s The Millennium, a 1924 satirical comedy about the birth of post-apocalyptic socialism, the atomic weapon that kills all but eleven of the earth’s inhabitants uses “radiumite.” In Public Faces, a 1932 political satire by former diplomat Harold Nicolson, the “Livingstone alloy” leads to Livingstone bombs and Livingstone rockets.

In most of these accounts, an atomic bomb seems like nothing more than impossibly powerful dynamite, but one can glimpse a premonition of the real thing in the “gigantic mushroom of steam and debris” in Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men or the explosion in Krakatit: “The next moment, as if the darkness had been torn asunder, a pillar of fire leapt into the air, spread terribly and liberated a tremendous body of smoke.”

Or take this startling passage from The Final War, a 1932 novel by a German war veteran called Carl W. Spohr:

Suddenly his eyes were blinded by a dazzling aura of light, a huge white flame, encircled by an electric, blue radiance. Air rushed against him like a solid, burning wall and threw him back into the room….A pillar of dust towered over [the crater] writhing and whirling like a tornado Doehler was beside the lieutenant, clutching the window frame in trembling hands. “My God, he has set it off. And the power of the atoms is free. I wanted an explosive, I did not want to do this. It is awful.”

Robert Cromie’s premise of a terrorist-scientist who actively wants to destroy the whole world also remained popular.

In Wings Over Europe, a hit 1928 play by Robert Nichols and Maurice Brown, the prime minister’s troubled genius nephew has harnessed the power of the atom for the good of all mankind, but when his uncle’s cabinet, stuffy and circumspect, orders him to destroy his discovery, he turns genocidal: “To assist Nature correct one of her casual blunders, I, who gave Man his opportunity, am about to take it away. In a brief moment this planet and all upon it, with all its history, its hopes, and its disillusions, will be wiped out.”

In J. B. Priestley’s 1938 thriller The Doomsday Men, three brothers conspire to cancel the world for different reasons: a disenchanted tycoon wants to end human suffering for ever, a scientist wants to erase the “accident” of life, and a preacher wants to bring on the apocalypse. “They want to destroy everything, everything,” says the tycoon’s daughter. “They believe life’s hopeless, that it’s all gone wrong, that it would be better if people were no longer born, just to suffer pain and misery—so they want to end it all.”

In reality, though, world destruction is a fringe interest. Pierrepoint B. Noyes’s 1927 novel The Pallid Giant was far more prescient about the psychology of the Bomb. Noyes grew up in a utopian community established by his father, John Humphrey Noyes, near Oneida, New York.

It was amillennialist: Noyes’ father believed that the Millennium had already commenced and therefore perfection on Earth was possible. Noyes later became a Rhineland Commissioner for President Woodrow Wilson, helping to reconstruct Europe after the First World War.

In his novel, a diplomat who is worried about an arms race to create a “Death Ray” discovers documentary evidence that millions of years ago a highly advanced race invented a similar superweapon which drove it to extinction. The document’s author, Rao, describes how his species built an atomic disintegrator ray called Holor which was so efficient that neither defense nor retaliation were possible: a country either used it first, or not at all.

“I fear not their desire to kill,” says the politician Daril in Rao’s account. “Even they are not so wicked as to crave the death of millions. I fear their fear. They dare not let us live, knowing or even fearing that we have a power so terrible, to kill.”

For him, it stood to reason that fear of the consequences of using a superweapon would be outmatched by fear of the enemy using it first: that is the “pallid giant.”

Following this logic, Daril pre-emptively reduces every other nation in the world to a desert, but fear of Holor then leads to civil war. People keep using the weapon until there is nobody left alive except Rao, who cedes the world to our proto-human ancestors. The known history of the world is therefore post-apocalyptic.

The Pallid Giant ends with the question of whether the Death Ray will be the new Holor and history will repeat itself. While working to prevent a second world war, Noyes had to consider how suspicion of the other side’s intentions had been the main driver of the first. For him, it stood to reason that fear of the consequences of using a superweapon would be outmatched by fear of the enemy using it first: that is the “pallid giant.”

By the 1920s, two camps had formed with opposing assumptions about the psychology of a superweapon—assumptions which foreshadowed Cold War arguments about nuclear deterrence. Contra Wells and Edison, Noyes thought that the only way that a superweapon would end war would be by finishing off the entire race.

______________________________

Excerpted from Everything Must Go: The Stories We Tell About the End of the World by Dorian Lynskey. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Dorian Lynskey.