The Christianization of Europe was mostly a “top-down” affair. A chieftain or a prince was baptized, and his people followed suit. For example, three thousand people are said to have followed Clovis when he converted to (Catholic, not Arian) Christianity. The religion was indispensable for the creation of stable social systems, as it formulated patterns of social order and provided justifications for them. Christening sanctified power, cloaking it in legitimacy. Baptized rulers could join themselves and their clans to other families of Christian Europe through marriage and by acting as godparents. Their lands were open to missionaries bearing gifts: salvation and literacy, culture and knowledge of the art of government.

Article continues after advertisement

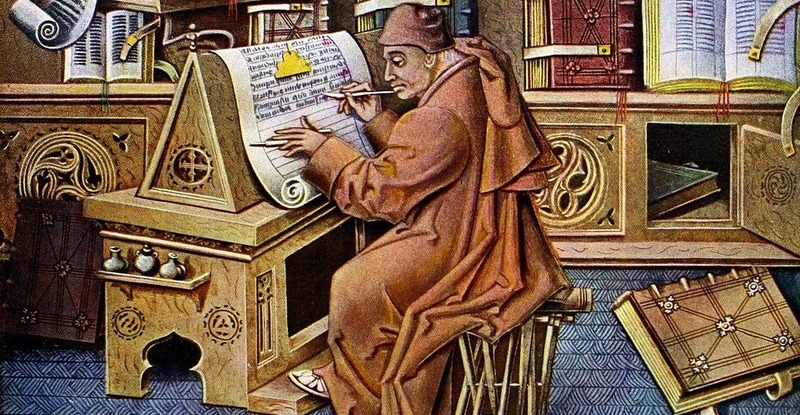

The spread of the Christian faith was accompanied and promoted by a further spread of monasticism. The importance of monasteries for the emergence of the Renaissance can hardly be overstated. Their number increased many times over from the sixth to the fifteenth century, from about one thousand to over twenty thousand. They were agents of cultural transmission. While pestilence crept over the walls of cities and the countryside fell into desolation—many foreign conquerors of Europe knew how to fight and plunder but not to plow or sow—the monks preserved words. When not engaged in prayer, monks worked in the scriptorium till their eyes were glazed over, their backs bent, their fingers stiff.

An experienced scribe could manage to produce seven pages per day of twenty-five lines each. Scribite, scriptores, ut discant posteriores—this inscription in the scriptorium of the monastery of Notre Dame de Lyre is said to have spurred the monks on: “Write, scribes, so that posterity may learn!” And that is exactly what they did. They passed down the intellectual cathedrals built by the Church Fathers, recorded saints’ lives, and spun yarns about miracles. They copied chronicles that gave their tiny monastic worlds a place in the grand historical drama between the Fall of Man and the Last Judgment. Scribes were assisted by illuminators, most of whom were also monks. Bookbinders put Bibles, Psalters, and books of hours between covers glittering with gold, jewels, and enameled images.

The importance of monasteries for the emergence of the Renaissance can hardly be overstated.

This celestial splendor indicated how precious the contents were. Some illuminators proudly signed the product of their artistry, while others immortalized the ordeal of copying. “This parchment is hairy,” moaned one. Another sighed, “Thank God it’s almost dark!” And a third, “I’ve finished copying the whole thing. Give me something to drink, for the love of Christ!” The grind of the scriptorium is also encapsulated in the curse that the illuminator Hildebert—who drew the scene with his assistant Everwin in the foreground—hurled (along with a sponge) at a mouse nibbling at the bread next to him on the table: “Wicked mouse, too often have you provoked me to anger! May God destroy you!”

Sometimes the scribes received pagan texts to copy. In this way, they kept the spirit of the ancients alive and created an abode for the family of pagan authors, often without intending to do so or even realizing it. They helped keep the works of compilers, encyclopedists, and translators in circulation, thereby preserving the ideas they contained. When they copied Boethius, they simultaneously kept Plato and Aristotle in the world. When they studied writings by the Venerable Bede, they also read parts of Pliny’s Natural History. It was above all Italian monastery libraries, stores of knowledge for the schools that sprang up around them, where many ancient texts survived. Beginning in the sixth century, a wave of monastic foundations washed back over the continent from England and Ireland, which had been the focus of early Christianization efforts.

The geographer Strabo had speculated that such areas were inhabited by wild cannibals vegetating in the cold, who ate their own parents and engaged publicly in sexual intercourse with any women they chose, including their own mothers and daughters. It is remarkable that Europe now received a civilizing nudge from its own rough borderlands. This was primarily thanks to a missionary impulse sent out by Pope Gregory, who, concerned about the upcoming Day of Judgment, thought it was high time to save souls. The earliest mission was centered in the county of Kent, with Canterbury as its main town. Its bishop rose to become the head of the English Church. Columbanus (ca. 543–615), a monk from the northern Irish monastery of Bangor, founded Luxeuil Abbey amidst the forests of the Vosges Mountains.

He also founded Bobbio Abbey outside Piacenza, with its rich library. The Abbey of Saint Gall, originally a hermitage south of Lake Constance, was founded by one of his companions, Saint Gall (or Gallus). Some missionaries, such as Kilian and Boniface, paid with their lives for their holy zeal—the former in the area of what is now Würzburg, the latter in Frisia. Columban monasteries remained free of the control of local bishops and were instead directly subordinate to the pope. Sharing all things in common and renouncing everything but what was necessary for survival required a rational, methodical lifestyle, and it was this that would ultimately enable monasticism’s significant achievements in philosophy, art, and economics.

Some monks emerged as transformers of the ancient tradition that was passed down to them. A highly original mind known as the “Irish Augustinian” tried to explain biblical miracles, such as the transformation of Lot’s wife into a pillar of salt, with Aristotelian arguments. As he reasoned, God allowed the salt already available in her body—it could be tasted in her tears—to multiply until it took over the whole. In line with the principle of entelechy, the matter then sought to realize the perfection of its nature in the appropriate form. One small intervention on God’s part caused Lot’s poor wife to solidify naturally.

Ireland’s exceptional role in preserving the ancient heritage (and Celtic epics) was also related to the fact that it was largely spared the massive invasions that haunted the island of Britain from the ninth to the eleventh centuries. Many monks—long-haired figures with painted eyelids—had returned home to the islands from their journeys to Italy with books in their baggage. Benedict Biscop, founder of the double monastery of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow in Northumbria, traveled to Rome no fewer than five times—in part, one presumes, to get books. He or his successor, Ceolfrith, brought a magnificent Bible from Cassiodorus’s library to the North. Ceolfrith had three copies of it made in the late seventh century, one of which, the Codex Amiatinus, is still extant. Its miniatures reflect late antique taste. Along with the early medieval culture of the region, it has led scholars to speak of a “Northumbrian Renaissance.” It combined Roman and Irish cultural elements and is symbolized by the Ruthwell Cross, which contains both Latin letters and runes.

Antiquity was not in good repute everywhere. Nevertheless, the small band of monastic scribes did manage to preserve and pass on a great deal of ancient literature.

The most important representative of this early medieval renaissance of the ancient mind was the polymath Bede, known as “the Venerable” (672/73–735). His literary horizon stretched from the Aeneid and the works of the Church Fathers to Isidore’s Etymologies, the letters of Pliny the Younger, and the Natural History by the latter’s uncle, Pliny the Elder. His On the Reckoning of Time contains a method for determining the date of Easter, knowledge of which was indispensable for precisely calculating sun positions and the path of the moon through the zodiac. This work, which helped spread the use of the birth of Christ as a benchmark for chronology, was a cornerstone of computus, one of the most important scientific disciplines of the Middle Ages. It was the basis for performing rituals at the correct time and thereby pleasing God. Like magicians, priests must be precise for their enchantment to work.

Antiquity also survived in other English libraries. Aldhelm of Malmesbury (ca. 639–709/10), for example, who studied in Canterbury, knew Horace, Juvenal, Ovid, Lucan and, as always, Virgil. The poet was likewise studied in storm-tossed Iona, where monks also passed the time with the insolent Plautus and the gossipy imperial biographies of Suetonius. Of course, it only took one fire to ruin the work of hundreds of years of transmission. What treasures were destroyed in 477 when the Imperial Library in Constantinople, which supposedly contained 120,000 texts, went up in flames! One was a snakeskin several meters long bearing verses of Homer written in gold. Numerous book collections, including those belonging to Cassiodorus and Montecassino, were scattered to the winds over the course of time.

If a monk at the monastery of Hirsau wanted to take out a pagan book, there were two signs he could use (when the rule of silence was in force): he could scratch behind his ear like a dog, the symbol for pagans, or he could stick two fingers in his mouth as if he were gagging. No, antiquity was not in good repute everywhere. Nevertheless, the small band of monastic scribes did manage to preserve and pass on a great deal of ancient literature. Admittedly, their legacy was negligible compared to the enormous amount of knowledge that had been scribbled on papyrus in antiquity between Miletus, Athens, Rome, and Alexandria. Yet this trickle of knowledge—soon to be supplemented by new streams flowing to the West from far-flung Byzantium, Persia, and India, and then from Baghdad and other centers of Arab culture—would suffice to change the world.

__________________________________

From The World at First Light: A New History of the Renaissance by Bernd Roeck. Copyright © 2025. Available from Princeton University Press.