“For there is nothing covered, that shall not be revealed; neither hid, that shall not be known. Therefore whatsoever ye have spoken in darkness shall be heard in the light; and that which ye have spoken in the ear in closets shall be proclaimed upon the housetops.”

–Luke

*Article continues after advertisement

“There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time….You had to live—did live, from habit that became instinct—in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.”

–George Orwell

*

Propaganda—the means used to manipulate people’s minds, from radio broadcasts to newspaper headlines—pursues the subjects of totalitarian rule through their dreams; so too do storm troopers, the means used to impose physical terror, in countless dreams that I will not discuss here since they are so obvious (yet many people dream them nevertheless). However, when a middle-aged housewife dreams that the tiled stove in her living room has become an agent of terror, clearly this is a different kind of terror. Her dream was:

A storm trooper was standing in front of the large, old-fashioned blue tiled stove in the corner of our living room, where we always sit and talk in the evening. He opened the stove door and it started to talk, in a shrill, penetrating voice [here again we have the penetrating voice recalling the loudspeaker voices of the previous day]. It said everything we’d said against the regime, every joke we’d told. God, I thought, what is it going to say next? All my little comments about Goebbels? But at the same time I realized that one sentence more or less wouldn’t make any difference—the fact was, they knew everything we’d thought and said to people we trusted. Just then I remembered that I had always laughed at the idea of the house being bugged; actually, I still don’t believe that it is. Even when the storm trooper tied my wrists—he used our dog’s leash—and was about to take me in, I thought he was just playing, and I even said in a loud voice: “You can’t be serious, this can’t be happening.” [This same disbelief in unbelievable reality—this almost schizophrenic split between the person experiencing something and the person looking on—was consistently observed in the concentration camps.]

It is important to realize that this dream of reveries by the Nazi fireside dates from 1933. What today are political facts, everyday realities, were not yet even described in novels: Orwell’s ever-present Big Brother did not yet exist, nor did the surveillance and recording devices from the second half of the twentieth century, used without any particular political purpose against a “defenseless society.” (The most recent refinement is miniaturizing these devices to the point where they can be installed inside a cocktail olive.)

The Third Reich couldn’t install surveillance devices inside everyone’s home, but it could certainly take advantage of the fear it installed in the people themselves.

We now also know that the people living under dictatorship were the prototype for the individual in this “defenseless society.” But the housewife here, or the civil servant from the last chapter who dreamed about a “Training Bureau for the Installation of Eavesdropping Devices in Walls,” didn’t know any of that—and yet they did “know” it, precisely as the government wanted them to, and reproduced in the darkness of night a distorted form of what they had already experienced in the dark world of daytime.

The housewife knew what had occasioned this dream—a particularly revealing cause in this case—and included it of her own accord when retelling the dream: “At my dentist’s the day before, when we were discussing various rumors, I found myself, despite my skepticism about surveillance, staring at his dental equipment and wondering if there mightn’t be some kind of listening device attached to the machine.”

We here see someone right in the process of being turned into the victim of a type of terrorization that is difficult to grasp and still not fully understood: the terror arising not from the constant surveillance of millions of people, but from not knowing for sure how complete the surveillance is. Maybe this housewife didn’t believe that there really were microphones, but on that day she caught herself thinking that it wasn’t totally impossible, and she promptly dreamed the same night that “the fact was, they knew everything we’d thought and said to people we trusted.” Could there be any dream better suited to the aims of a totalitarian regime?

The Third Reich couldn’t install surveillance devices inside everyone’s home, but it could certainly take advantage of the fear it installed in the people themselves, driving them to terrorize themselves, as it were. The regime had turned its subjects, without their realizing it, into voluntary collaborators in the systematic terrorization, by making them think it was more systematic than it actually was. This “Dream of the Talking Stove” is, in its way, an example of blurring the line between victim and perpetrator: In any case, it reveals the endless possibilities there are for manipulating people.

The bedside lamp of another housewife soon joined the idyllic storybook nook of the cozy stove in betraying its owner. Instead of bringing light, it brought to light at loudspeaker volume everything she said in bed:

The lamp was speaking in a loud, shrill voice, like a military officer. At first I thought I would just turn it off and stay safe and sound in the dark. But then I told myself that that wouldn’t help. I rushed to see my friend, who owned a dream-interpretation manual, and I looked up “Lamp”: the only definition in the book was “Serious illness.” It was a big relief, but only for a moment, until I remembered that nowadays, to be safe, people were using “sickness” as a code word for “arrest.” Again I felt desperately worried, at the mercy of that shrill voice that never stopped talking, even though no one was there to arrest me.

A greengrocer dreamed exactly the same thing about the pillow he put on top of the telephone as a precaution when his family was sitting comfortably chatting together in the evenings. The comfort turned to horror when this pillow, which had been embroidered in cross-stitch by his mother—a sentimental memento he kept on his easy chair, his domestic throne—suddenly grew a tongue and started testifying against him, incessantly repeating all the family conversations from the price of vegetables to the midday meal to the sentence: “The fat guy’s getting fatter and fatter” [meaning Hermann Goering]. All the while the greengrocer couldn’t believe what was happening to him, any more than the housewife by the stove could.

I heard about similarly uncanny household objects many times: mirror, desk, desk clock, Easter egg. In each of these cases, the dreamer didn’t remember the whole dream, only that the object was denouncing them. The number of these dreams may have increased as people learned more about the regime’s methods. But even these examples from the housewife and the greengrocer, who dreamed about Big Brother’s listening ear if not his striking fist—people who also had imposed censorship, tyranny, and terror on themselves during the day, otherwise it would have been hard for them to invent these new domestic tyrants at night—illustrate more than the invisible methods of silencing millions of housewives and greengrocers. They illustrate too the dark shape that these people’s “consent” takes. They show how people, in blind fear of the hunter, start to play the hunter themselves, as well as the prey; how they secretly help set and spring the very traps that are meant to catch them.

One dream in this category—grotesque enough to be in a class by itself—came into my hands only recently:

I dreamed that I woke up in the middle of the night and saw that the two angels hung above my bed were no longer looking up—they were looking down, keeping a sharp eye on me. I was so scared that I crawled under my bed.

Apparently the girl who’d had this dream had had one of the popular reproductions of the putti from the Sistine Chapel above her bed. The dream sounds unremarkable enough, but only at first: She had never realized that these angels stationed to watch over [wachen über] her sleep were in fact over-seers, monitoring [überwachen] her, and she crawled under her bed as though she had learned from George Orwell that it’s impossible to know whether or not you’re being watched at any given moment.

The regime had turned its subjects, without their realizing it, into voluntary collaborators in the systematic terrorization.

With one more turn of the screw, the various precautionary measures taken by day, the disguises and camouflages (also used, of course, in modern art), the bizarre and elaborate rules that private people adopted to try to outwit public rules and laws both real and imagined—these, too, would come to life in dreams. One young woman, who worked as an excellent bibliographer, had this dream:

I was going to visit a friend, whose name was, let’s say, “Klein” [German for small]. As I was walking there, I realized I had forgotten her exact address. I went into a phone booth to look it up, but as a precaution I looked up a totally different name, let’s say “Gross” [German for big], which was obviously pointless. [So said the woman herself, whose job was looking things up!]

This is a literally crazy thing to do, since the action itself defeats the purpose of the action. But it makes so much sense within the craziness of the dreamer’s world—it is not at all absurdity for absurdity’s sake.

Here is another example, in a single sentence:

I was telling a forbidden joke, but I was telling it wrong on purpose, so it made no sense.

The same man who dreamed this also dreamed about blind and deaf people he sent out to see and hear forbidden things, so that he could prove whenever he needed to that they hadn’t seen or heard anything. He remembered no further details about this obviously farcical procedure.

The most precise example I heard of this kind of dream was from a hatmaker, from the summer of 1933:

I dreamed that I was talking in my dream and to be safe was speaking Russian. (I don’t speak any Russian, and also I never talk in my sleep.) I was speaking Russian so that I wouldn’t understand myself and no one else would understand me either, in case I said anything about the government, because that’s against the law and would have to be reported.

“Come, let us go down and there confuse their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech,” it says in the Bible; during the Inquisition, a man was prosecuted for having “spoken heresy in his dream”—the hatmaker surely knew neither of these things. Nevertheless, what she dreamed has since become reality, in Auschwitz, where the impossible became possible: A female prisoner working as a secretary there fearfully asked another woman who slept in the same room if she had said anything in her sleep about what had happened the previous day. “Because we were threatened with punishment if we said a single word about what we’d heard in the political branch, or even conveyed anything with a facial expression.” (Quoted from testimony at the Auschwitz trial reported in Die Welt.)

A young man had this dream at around the same time:

I dreamed that I had stopped dreaming about everything except rectangles, triangles, and octagons, which all looked like Christmas cookies somehow. Because we weren’t allowed to dream.

Here we have someone who decided to play it safe by dreaming about no physical objects at all.

__________________________________

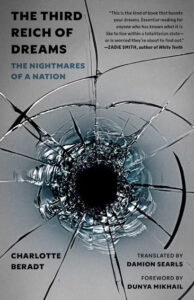

From The Third Reich of Dreams: The Nightmares of a Nation by Charlotte Beradt. Translated by Damion Searls and Foreword by Dunya Mikhail. Copyright © 2025. Available from Princeton University Press.