This story is well-worn local lore, yet still little known beyond the territories of present-day north-central Washington State. But the story bears significance well beyond the remoteness and seeming inconsequence of its place: as a long overdue contribution to the history of photography, certainly, and at least equally for what it illuminates about the history of US settler colonialism at the micro-level of its regional transformations and interpersonal relations.

Indeed, the region’s uneven, overlapping histories resonate with that larger settler colonial narrative, which remains conspicuous in its geography: comprised of the Colville Indian Reservation and its twelve confederated tribes; the southern ancestral lands of the Syilx Okanagan Nation; and the settler towns of Okanogan, Omak, Conconully, and dozens of others—all part of the world of the Indigenous (Columbia) Plateau and the Native peoples who have lived on its lands and cared for them since time immemorial. Immersed in this history, this story begins with the arrival of a stranger thirty years after the forced establishment of the Colville reservation in 1872.

In 1903, a Japanese immigrant named Frank Sakae Matsura moved from Seattle to Conconully, then to newly built Okanogan, from a cosmopolitan city steadily growing as a major trade and shipping center to what would have appeared to most city dwellers as the middle of nowhere. A handsome, impish extrovert, good old Frank quickly befriended seemingly everyone in the local communities. He also hauled quite of bit of photographic hardware to this apparent middle-of-nowhere; set up a photography studio and gift shop; and, as a beloved resident, proceeded to take thousands of photographs of its people, places, and events until his untimely, unexpected death caused by tuberculosis in 1913.

Matsura’s photographs were prized by the locals to whom he sold and gifted his work, and they gained limited recognition and circulation beyond: magazine illustrations used to entice potential homesteaders back east; celebrated submissions to the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle; scenes of industry and agriculture used in a 1911 Great Northern Railway advertising campaign; and the thousands of postcards sent by locals to family, friends, and others elsewhere.

After Matsura’s death, a substantial collection of his photographs, bequeathed to his friend Judge William Compton Brown, was donated as part of Brown’s estate to the Washington State University archives. However, thousands of fragile gelatin dry glass plates on which his photographs were recorded remained stored in a garage in Okanogan, undiscovered until the mid-1970s; the late historian JoAnn Roe selected and introduced some 140 of these photographs in an elegant, small-press book, Frank Matsura: Frontier Photographer, that was published in 1981.

Although it soon went out of print, the volume garnered sporadic attention for Matsura’s work over the next three decades. Since the 2010s, however, his photographs have started to appear with greater frequency and impact in small exhibitions throughout the Pacific Northwest, earning Matsura an ever-widening circle of admiration and appreciation.

Over the span of a near decade from 1903 to 1913, with unflagging enthusiasm and dedication, Matsura visited seemingly everyone and everywhere with his “magic box” and tripod in hand—sometimes with at least two, since several photographs portray Matsura posing with one of his cherished cameras. Hence, his photographic archive provides a comprehensive visual record of the region’s colonial settlement: infrastructural development including the founding of his adopted hometown, Okanogan, construction of Conconully Dam, installation of electricity and waterworks, planting of orchards, extension of the railroads, and arrival of automobiles. And he produced portraits—serious and playful, formal and casual—of Native peoples and settlers alike, adapting to the modernization of the Indigenous Plateau.

Matsura did not impose any particular interpretive frame onto his subjects and certainly not a dominant cultural belief or perspective with which he may or may not have been familiar.

The most remarkable quality of this body of work, however, is the manner in which it unsettles and departs from the perspectives and conventions of canonical American West photography and studio portraiture. This radical difference is most evident in his portraits of the region’s Native peoples, which art historian ShiPu Wang felicitously characterizes as “imagery of the Other by the Other”: a counter archive of American Indian representation produced by an eccentric, educated Japanese immigrant, whose motives for relocating to Okanogan remain undetermined.

The canonical work of Edward Curtis established the tragic view and elegiac rhetoric of Native people as noble savages unassimilable to Progress and hence destined for cultural, if not biological, extinction. Even the preceding work of distinguished white male photographers like William Henry Jackson and Lee Moorhouse participated in this romanticizing project. Jackson, celebrated for his iconic landscapes of “untouched” Western landmarks, documented the tribes that his Union Pacific and US Geological Survey expeditions encountered not for themselves, but as features of the unincorporated territories to be transformed by the inexorable force of westward expansion. Moorhouse, like Matsura and unlike Curtis or Jackson, was a resident of the Pacific Northwest (and additionally a federal Indian agent) who had long-standing relationships with the tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

Yet he, too, adopted and produced a romanticizing view of his Indian subjects: like Curtis, Moorhouse staged his portraits to better conform to his ideal of melancholic authenticity, costuming Indians with clothing and artifacts from his extensive Native wardrobe and posing them stoically, to exemplify the Indian way of life that he believed would disappear as a fatalistic corollary of Manifest Destiny.

Arguably, the single image most responsible for codifying this trope is Edward Curtis’s 1904 masterpiece, The Vanishing Race: a group of Navajo on horseback slowly riding into the perspectival distance of the photograph—vanishing, metaphorically, into the past. The image was so vivid and memorable that it appears to have served as the template for the closing passage of Zane Grey’s popular, if controversial, 1925 novel, The Vanishing American: against a “magnificent, far-flung sunset…the Indians were riding away.” Grey continues: “It was an austere and sad pageant….Far to the fore the dark forms, silhouetted against the pure gold of the horizon, began to vanish, as if indeed they had ridden into that beautiful prophetic sky….At last only one Indian was left on the darkening horizon—the solitary Shoie—bent in his saddle, a melancholy figure, unreal and strange against that dying sunset—moving on, diminishing, fading, vanishing—vanishing.”

To be sure, Grey’s novel is a literary protest against the mistreatment of American Indians by the federal government and Christian missionaries, and his original denouement is a little more complicated. In it, Nophaie, the novel’s Indian male protagonist, and Marian, his white female companion, plan to marry and live on the reservation as they watch the survivors of Nophaie’s tribe “vanishing” into the sunset. The press, however—fearing backlash to its positive depiction of interracial romance—rewrote the conclusion without Grey’s knowledge or consent, killing off Nophaie and the offending prospect of miscegenation. Grey’s son, Loren Grey, restored his father’s original ending in the novel’s 1982 Pocket Books reprint, but the vanishing mythos remains intact, with the last of the tribe wistfully following Curtis’s Navajo into the temporal graveyard of the past.

Matsura’s photographs stand in sharp contrast to this powerful, prevailing myth. Unlike his more prestigious white male counterparts, Matsura did not impose any particular interpretive frame onto his subjects and certainly not a dominant cultural belief or perspective with which he may or may not have been familiar. (And if he knew about it through reading or his visits to Seattle, evidently he didn’t buy it.) Instead, his photographs are distinguished by, as Colville tribal artist and curator Michael Holloman puts it, “conceptually sophisticated and collaborative portraits of individuals and families with whom Matsura maintained trusting relationships.” He did not ventriloquize through his subjects; he enabled them all, settlers and Natives alike, to present themselves to themselves and others, on their own terms. Hence, contrary to the melancholic archive of vanishing Indians inexorably dying off to make way for settler colonial modernity, Matsura’s work instead illuminates what Anishinaabe writer Gerald Vizenor calls “survivance”: “renunciations of dominance, tragedy and victimry” and the “active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories, not a mere reaction, or a survivable name.”

This “active sense of presence” is seen and felt in Matsura’s just-visiting portrait of his friend Chiliwhist Jim, Methow medicine man: we don’t know why he’s in town, but he rides and carries himself with purpose. Front and center frame, Chiliwhist Jim presides over the scene, and the camera, while the white men and their dog sit or stand idly, receding into the perspectival distance behind him. Ironically, although this photograph in itself does not reveal it, the clock is broken with its arms forever frozen at 8:17, the same time as it appears in other photographs. In any event, Chiliwhist Jim has business to attend to and is not here to wait for his extinction or ride off into the past.

More broadly, what kinds of stories of survivance do these photographs enable, support, and continue? At the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane, Washington, at a panel event commemorating its extraordinary exhibition of Matsura’s photographs, curator Holloman intriguingly remarked that “Frank was a coyote.” Of course, shape-shifting Coyote ranks among the most venerated Animal People throughout Indian country, who “amused himself by getting into mischief and stirring up trouble,” according to Mourning Dove, esteemed Okanogan and Colville writer of the 1920s and 1930s.

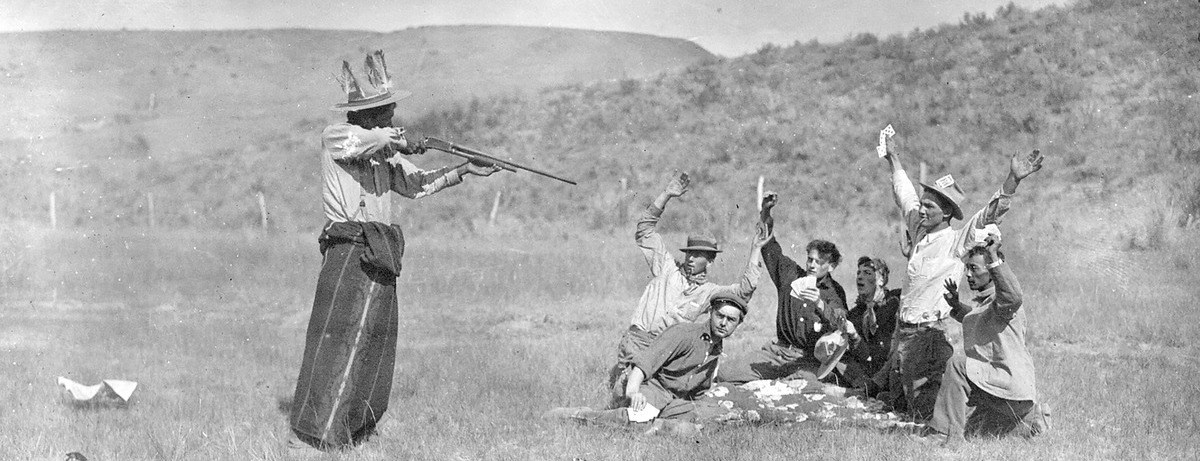

Further, Coyote “delighted in mocking and imitating others, or in trying to, and, as he was a great one to play tricks, sometimes he is spoken of as ‘Trick Person.’” This is not to suggest that Matsura was Coyote personified; rather, that Matsura’s persona and perspective manifested trickster qualities inscribed in and expressed through his photography. Contrary to his canonical white counterparts, who passed off their fictionalizing display of Indians as authentic and true, Matsura’s photographs often mirthfully reveal their ruse—like Belgian surrealist René Magritte’s 1929 painting The Treachery of Images, baldly divulging, “This is not a pipe.” Take, for example, an outdoor scene that the Okanogan County Historical Society captions thus: “A staged scene of a Native American man with feathers in hat band and blanket using a rifle to stop a card game among six men on a blanket.”

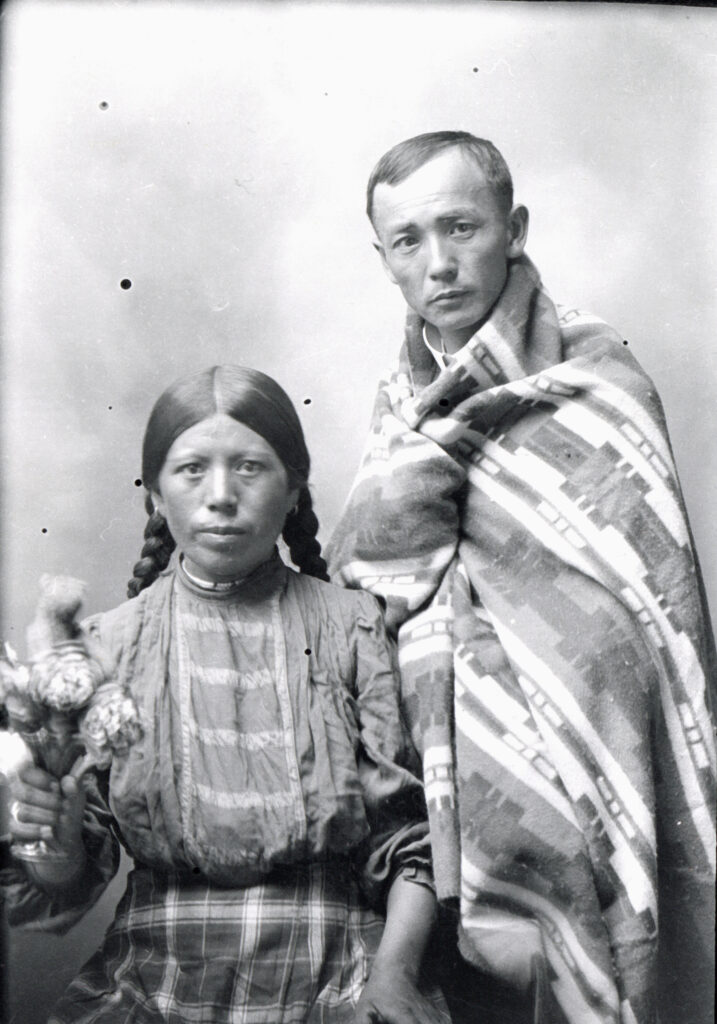

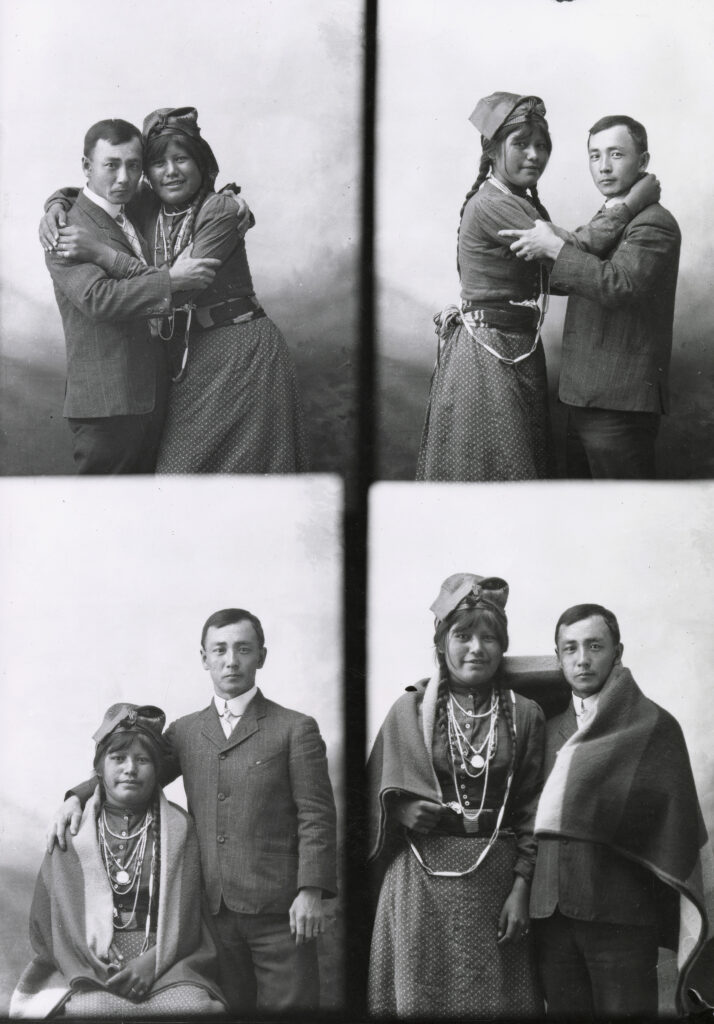

Whose idea was this, and what kinds of settler-colonial relations does this mock holdup invert? The joke is evident in the photograph itself. Presumably, everyone is in on it; but who is the joke on, and for whom? The answers may well depend not only on whether we ask these questions in 1910 or today but on which side of the Okanogan River—settler towns or Colville reservation—we pose them. Likewise, reflect on a series of twelve portraits in which three young white men, Matsura, and his friend Cecil Jim (niece of the imposing Chiliwhist Jim) assume different pairings and playfully switch hats.

What do we make of this cross-racial chumminess between the sexes in 1910 Okanogan, on the settler side of the river? In photographs taken outside the studio, we see no such casual sociability, and certainly not flirtiness, across race and sex and perhaps class, as well. Indeed, Matsura’s work, as Colville (Entiat) engineer and writer Wendell George says of Coyote, “made you realize that things were not always the way they seemed to be.” Throughout his archive of Coyote photography, colonial settlement of the Indigenous Plateau—landscapes—and the fate of its first peoples—portraiture—are not what they, in the canonical record, seem to be.

__________________________________

From Frank S. Matsura: Iconoclast Photographer of the American West, edited by Michael Holloman. Copyright © 2025. Available from Chronicle Books.