I grew up three hundred miles from the nearest city with a million people, so I never grew up calling anywhere “the city,” but this phrase often indicates the suburbs’ focal point, those on the edges longing for the epicenter. Maybe this is why Sex and the City’s lessons often feel a bit remedial. Season one has a hilarious episode about the brave new world of rabbit vibrators, and the next week “The Baby Shower” aired, a similarly ballsy condemnation of suburban motherhood as a lobotomizing cult.

Article continues after advertisement

But the next episode shows Carrie fretting over whether her accidentally farting in front of her boyfriend has made him lose all desire for her. I have trouble believing that any woman who has reached the age of thirty—one whose job is writing about sex and relationships—believes she has successfully created the illusion that she never farts.

Used to these madcap storylines, the Sex and the City fan might find the book it is based on a bitter pill to swallow. Compiled from Candace Bushnell’s column of the same name from The New York Observer, the book is a dark and bizarre look at dating in 1990s New York, where men are pathologically childish, cruel, and self-centered, and women are domineering, striving, and manipulative.

“Relationships in New York are about detachment,” one interviewee tells Bushnell, and they would have to be, when she is writing case studies of men who are fixated on dating models and women who, when they get the family they’ve schemed for, are incestuously obsessed with their own infants. Bret Easton Ellis is said to be the basis for one of the book’s pseudonymous characters (bad-boy novelist “River Wilde,” LOL), and Bushnell’s subjects are all American psychos, people who have been made monstrous by an atmosphere of ambition, competition, and insecurity, both in social and economic spheres.

In the struggle between modernity and tradition, women’s roles and bodies are the concession we make to the past.

The dark edge in Bushnell’s writing reflects less a brave new world than a world that is the hideous extension of the old one. She references Edith Wharton’s novels of New York often, marveling at the excesses of a new Gilded Age like the one Wharton chronicled, where New York “high society” is a fickle system of hierarchies and arcane codes of conduct. As far as I could tell, The Age of Innocence is about two people who spend a lifetime not fucking, out of a deep sense of propriety, duty to family, and a paradoxical devotion to each other. (“I wanted Madame Bovary,” I told my husband after finishing it, “and I got Madame Very Boring.”) Sex and the City, on the other hand, is about a world where love, the most abundant substance in the universe, is profoundly scarce, and people feel no sense of duty except to their own images, bank accounts, and addictions.

The other reference Bushnell gets the most mileage out of is to the legendary Cosmopolitan editor Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl, from which the title Sex and the City is drawn. Brown’s 1962 how-to guide for modern single women to dominate both in relationships and at the office was radical in one way, advising women to cherish being single rather than seeing it as a sign of their deficiency. The book also foresaw (or maybe wrote the script for) a generation of girlbosses, casting women’s femininity and sexiness as their greatest tools for achieving liberation, since they allow them to manipulate men.

Brown’s archetypes of the men one meets on the dating scene like the “Don Juan,” the “divorcing man,” and the “homosexual” become Bushnell’s (and Carrie Bradshaw’s) humorous shorthands like “modelizers” and “Bicycle Boys.” By the time Sex and the City was published in 1996, Brown’s midcentury ideas of gender—with men cast as insensitive, impatient, and oafish and women as sexy, silly, and scheming—had calcified, constraining the childish, unfeeling fuckboys and desperate gold diggers and frigid career women of Bushnell’s New York.

This jokey pessimism about heterosexual relationships is the subject of much “chick lit,” an essentially 1990s genre of popular literature (of which Sex and the City is one notable example), concerning itself with the impossible situation of single, straight women who wanted to achieve some sacred nexus of social freedom, professional success, and romantic bliss. Standing in the way of this dream were the rules of feminine behavior they had been taught to live by, the punishing standards of beauty they were held to, and men’s wholesale refusal to acquiesce to even the most minor of feminist demands.

These books are comedies of manners, commenting through satire on the contradictory status of women in modern culture. Meghan Daum wrote that Bridget Jones’s Diary “concerns itself almost entirely with the neurotic fallout of popular women’s culture,” but of course that is the point of the book, that Helen Gurley Brown’s archetypal swinging single girl was an oppressive fiction, and her perfect job, apartment, body, and emotional equanimity were not achievable for almost anyone. But chick lit did not provide solutions for this feminist impasse even as it lampooned it, just as Jane Austen was not engaged in dismantling the British class system. In Bridget Jones’s Diary, her Mr. Darcy acts almost as deus ex machina: a nice guy comes along not to question why women have settled for so little but to signal that the story is over.

Chick lit both reflects and critiques essentialist ideas about gender and relationships that were so widespread in the ’90s that Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus was the highest-selling self-help book of the decade. The situation was ripe for comedy of the laugh-or-you’ll-cry variety: despite rounding on the second millennium CE, despite 60 percent of women working outside the home, despite powerful feminist and gay liberation movements in preceding decades, there was still a belief that heterosexual marriage and family were the apex of fulfillment in American life.

Emily Witt writes in her book Future Sex, a collection of essays on how tech has shaped sexuality in the twenty-first century, about how free love is a common trope of early science fiction, representing as it did an innovative and complete break from current social norms. “Like outer space, the prospect of free love was always there,” Witt writes, “humans just had to figure out how to make it hospitable to our needs.” This attitude is present in Star Trek, though it does not seem to be an integral part of the series’ philosophy. On Next Generation, the crew members of the Enterprise are all heterosexual and most primly single. (The swashbuckling Commander Riker is a refreshing exception. He seems to be the only one who takes advantage of his travels around the galaxy to have affairs with sexy aliens.) The woman in the one married couple on board spends what feels like entire seasons heavily pregnant and then has a messy birth in the ship’s bar during a system failure. Like many people these days, Starfleet officers seem chill about the prospect of nonmonogamy but not up to trying it for themselves.

The anguish lacing through the satire-obsessed ’90s burns like a hangover, at the same time mocking and cherishing the inert residue of hope that history might keep moving forward.

My friend told me that whenever she watches Star Trek, she rants to her husband about how ridiculous it is that women on the Enterprise still experience nine-month pregnancies exactly like we do now. With their super-advanced medical tech, why wouldn’t they have remote incubation or a shortened gestation period, at least for those working on spaceships? For the same reason, I suppose, that there is still controversy over IVF and other forms of fertility treatments, nearly fifty years after the first test tube baby.

Despite how human industry has eliminated or degraded the world’s wild spaces, liberally meddling in the life cycles of animal and plant life, technologies that intervene on human sexuality and reproduction are still considered “playing God.” Sex is deeply if cynically intertwined in current ideas of what is natural and sacred, which is probably also why the only kind of plastic surgery politicians are interested in legislating on is the kind that changes the look and function of a person’s genitals. This appeal to nature baldly reflects patriarchal fears about the status of women if they were unburdened of the threat of pregnancy and the obligations of child-rearing.

Witt writes in Future Sex how the men who created the first birth control pill designed it so the patient would still have a completely unnecessary monthly period, simply because it seemed unnatural to eliminate it—and this is still a common feature of contraceptives today. It is exactly decisions like this that have kept women bound to the cult of motherhood when technology could have expanded our ideas of parenthood, family, and female identity. As usual, in the struggle between modernity and tradition, women’s roles and bodies are the concession we make to the past.

The issues that Star Trek broaches allegorically and Sex and the City explores through satire were real, and painful enough to keep Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus on the bestseller list. But they are also self-reinforcing. It takes no more gender theory than intuition to notice that we all contain masculine and feminine attributes, and “man” and “woman” are not always useful categories for unique human beings, particularly in our idiosyncratic intimate relationships. How many people did not realize they lived in a world where men and women were so different that they might as well come from planets seventy-five million miles apart until they were told?

As Susan Faludi illustrated exhaustively in Backlash, ideological forces in the 1980s and ’90s, as incarnated not only in governments but by academia, journalism, and popular entertainment, were highly invested in promoting the questions of sexuality and gender as a dangerous and unsolvable mess, making cleaving to traditional family structures and gender roles a can’t-live-with-them, can’t-live-without-them situation. There exists underneath this message a reproach of twentieth-century radical movements in general, although the women’s movement was a popular punching bag: life was absurd, liberation was impossible, and compromise was the only way forward, even when we were compromising our deepest desires. The anguish lacing through the satire-obsessed ’90s burns like a hangover, at the same time mocking and cherishing the inert residue of hope that history might keep moving forward, rather than oscillating stupidly between revolution and revanchism.

__________________________________

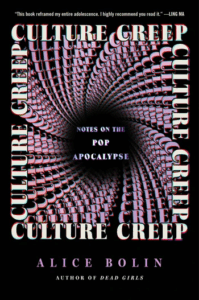

From Culture Creep: Notes on the Pop Apocalypse by Alice Bolin. Copyright © 2025 by Alice Bolin. Reprinted courtesy of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.