Tacoma is famous for one thing: its smell. If Seattle is considered a remote backwater in the 1950s—and it is—then Tacoma, poor sister to the south, is even more remote, more philistine, beneath contempt. Tacoma is Seattle’s industrial flunky, the also-ran, the perennial embarrassment. Its setting once bore the rich grandeur of the Northwest, framed by mountains, royal robes of evergreens trailing into the placid harbor of Commencement Bay. Before white men arrived, it was a natural oasis, but Tacoma’s forefathers took that charm and threw it away with both hands. In 1873, having commissioned a design by Frederick Law Olmsted laying out the town in a series of curvilinear terraces beautified with seven parks, city planners reacted with “a bemused blend of boosterism and dismay.” During a recession, they rejected Olmsted’s vision.

Article continues after advertisement

Instead, the town on Commencement Bay, considered one of the five best natural harbors in the world, chooses industry at every turn, buoyed by a brief boom associated with the building out of the Northern Pacific Railway, battening on the smoke and stench of wood pulp and paper mills, lumberyards, oil refineries, chemical plants, rendering plants, sewage tanks, and smelters. What is a smelter? It is a commercial volcano, melting rocks for metal.

It is the Götterdämmerung. If you are one of those people who think rock is a solid, think again: it burns.

Tacoma is Seattle’s industrial flunky, the also-ran, the perennial embarrassment.

Soon the waste and effluent and slag heaps are strewn beside the bay and across the Tacoma tidal flats like offal dropped from a raptor’s nest. Fifty-three industrial plants are invited to squat there, in the center of the city, and the smell of decomposition and putrefaction and acidification, a stew of sulfur, chlorine, lye, and ammonia, suffuses the air. The staggering odor is called, as early as 1901, “the aroma of Tacoma.”

*

“Tacoma’s Poison Factory Is Interesting Industry,” the Tacoma News Tribune notes approvingly in 1927. It is indeed. So much is already known. In 1913, chemist Frederick Gardner Cottrell delivers a paper on “The Problem of Smelter Smoke” to the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco, in a city where the Selby Lead and Silver Smelting Works has been pumping lead into the air since the 1870s. Selby is soon to be acquired by American Smelting and Refining.

Cottrell lays it out clearly: “The problem of smelter smoke is entirely distinct from that of ordinary city smoke,” he says, explaining that the constituent parts “cannot be simply ‘burnt up.’” The chief offenders, he admits, are these:

Sulphur—Chiefly as sulphur dioxide, a colorless, invisible gas, but to some extent, as sulphuric acid, a liquid.

Arsenic—Usually as the oxide, a white solid.

Lead—Usually as the sulphate, a white solid, of the sulphide, a black solid; but sometimes the oxide, a yellowish solid.

Zinc—Chiefly as the oxide of sulphate, white solids.

*

In the 1920s, Tacoma’s poison factory becomes one of the largest producers of highly refined colorless, tasteless inorganic white arsenic, shipping it all over the country. It is one of the most hazardous substances known to man. In contrast to organic arsenic, a largely harmless compound commonly found in seafood, less than an eighth of a teaspoon of the inorganic powder can be fatal to an adult.

In 1923, the United States produces more than fourteen thousand tons of white arsenic domestically, but demand is so high that it must import ten thousand additional tons. Farmers dust those twenty-four thousand tons onto crops that year, killing codling moths and protecting stone fruit in the great growing regions: California’s Central Valley, Oregon’s Hood River Valley, and throughout eastern Washington. Apple, apricot, peach, pear, and cherry trees are treated with it.

On January 31, 1939, a hundred miles north of Huron, not far from the town of Aberdeen, where the tornadoes of L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz roam, Mrs. Henry Brudos gives birth to her second son, Jerome, called Jerry. Jerry’s father is an angry little man, five feet four, who is trying and failing to support his family on a South Dakota farm during this time of drought and grasshopper infestations. Decades later, farms to the north of his will form one of the largest Superfund sites in the Great Plains, the Arsenic Trioxide Site, covering twenty-six townships and 568 square miles, an area in which the poison has long since penetrated groundwater and seeped into wells. For years, it’s not uncommon for South Dakota kids to uncover sacks of old grasshopper bait—arsenic or lead arsenate—in barns or old corncribs. Newspapers urge farmers to dispose of the stuff safely, lest it present a health hazard “to children, pets, and livestock.”

Little Jerry is “sickly.” He suffers from swollen glands, laryngitis, recurring sore throats, and fungal infections around his fingernails and toenails. He has migraines so severe they make him vomit and undergoes two operations to treat swelling in the veins of his legs. “Vague and slow,” he fails the second grade. Long-term exposure to the pesticide is associated with headaches, fungal infections, red and swollen skin, and sore throats. Neurological effects, according to specialists, are “many and varied.”

Jerry also develops, as a young child, a strong and virtually irresistible attraction to women’s high-heeled shoes. By his teens, having moved to the Pacific Northwest, he becomes known to local authorities for knocking women down on the street and stealing their footwear. How about a little arsenic, Scarecrow?

*

By the time the Depression rolls around, Tacoma is so steeped in violence that it has become a birthplace of noir. There, in 1920, a broken-down Pinkerton detective named Sam Hammett, exhausted by wrangling with union agitators in the mining towns of Montana and Idaho, is wiling away dull hours in a tubercular ward by reading the local newspapers, replete with vice and crime.

Later, using his middle name, Dashiell, Hammett begins his first novel with a description of a town he calls Poisonville:

The city wasn’t pretty….The smelters whose brick stacks stuck up tall against a gloomy mountain to the south had yellow-smoked everything into uniform dinginess. The result was an ugly city of forty thousand people….Spread over this was a grimy sky that looked as if it had come out of the smelters’ stacks.

When he publishes his masterpiece, The Maltese Falcon, it contains a famous passage inspired by Tacoma. The mysterious bird of the title, which costs so many lives, turns out to be fashioned not of jewels but of lead.

Dark doings—abductions, intrigues—fill the Tacoma papers. In 1921, Henry Arthur Rust, William Rust’s twenty-year-old son, is picked up and held at gunpoint while walking to work. A bomb threat and ransom demand for $25,000 appears. But when Arthur is released unharmed, rumors fly that the whole thing was a plot contrived by the son to extort money from his father. The would-be kidnapper, Hugh Van Amburgh, whose father is a master mechanic at the Ruston smelter, knows Arthur and testifies to the hoax at his trial.46 Conveniently for Arthur, however, Van Amburgh recants months later, pleading an overindulgence in “moonshine” and temporary insanity.

The city gains national notoriety when nine-year-old George Weyerhaeuser, great-grandson of the timber dynasty’s founder, is seized off the street on May 25, 1935, as he leaves school on his way to meet his sister. His parents receive a ransom letter demanding $200,000. Waiting for a response, the kidnappers stash the child, chained, in a hole they have dug near Issaquah, a small agricultural burg on the shores of Lake Sammamish surrounded by Cascade foothills—Tiger Mountain, Cougar Mountain—burying him alive.

Nervous that authorities may be closing in, they soon pull him out, driving him to Spokane and then back again. After they collect their money, they leave the boy standing on a logging road at midnight with a dollar and a blanket. After walking for miles, George finds a farmer’s house and is restored to his family.

Lead is a vampire. Invite it in and it will drink your blood and live forever.

For George, it has a happier ending than the kidnapping that preceded it, that of the Lindbergh baby. But in turn it inspires another the following year. On the evening of December 27, 1936, a masked man begins pounding on the French doors of a Tudor mansion perched on the ridge overlooking Ruston and Commencement Bay, owned by a well-known and wealthy Tacoma physician.

The children within are home alone, drinking root beer and eating popcorn in the living room: ten-year-old Charles Fletcher Mattson, his teenage siblings, and a friend. Terrified, they refuse to open the locked doors, but the intruder, armed with a revolver and described as “swarthy,” breaks the glass, snatches Charles, and escapes, dashing down an embankment toward Ruston Way, along the edge of the harbor.

J. Edgar Hoover sends forty agents to the scene, hoping to sort out a welter of confusing ransom notes demanding $28,000 in “old bills.” But on January 11, 1937, a young man hunting rabbits south of Everett finds Charles’s naked, battered body dumped in a thicket of alders, knifed in the back and beaten in the head with a blunt instrument.

National media coverage is so intense—the sense of outrage so unrelenting—that President Roosevelt issues a public statement the day after the discovery, announcing a $10,000 reward. “The murder of the little Mattson boy has shocked the nation,” he says. “Every means at our command must be enlisted to capture and punish the perpetrator of this ghastly crime.” The kidnapper is never apprehended. The murder of Charles Mattson, a capital crime with no statute of limitations, remains an open case.

From here on, Tacoma cannot shake its reputation as the kidnapping capital of the West.

*

Year after year, lead is flying out of the smokestack. What is lead? It is a poison, second in toxicity only to arsenic. It is a chemical element bearing the atomic number 82 and the symbol Pb, from the Latin plumbum. In its solid phase, it is a shiny gunmetal gray, excruciatingly heavy. It burns with a white flame. It’s resistant to corrosion. It never disappears. It enters the world in many ways, including but not limited to “oil-processing activities, agrochemicals, paint, smelting, mining, refining, informal recycling of lead, cosmetics, peeling window and door frames, jewelry, toys, ceramics, pottery, plumbing materials and alloys, water from old pipes, vinyl mini-blinds, stained glass, lead-glazed dishes, firearms with lead bullets, batteries, radiators for cars and trucks, and some colors of ink.”

Lead is a vampire. Invite it in and it will drink your blood and live forever. It tastes sweet. Chemically, it resembles calcium and is taken up rapidly in the bodies of children as their bones are forming. In ancient Rome, where winemakers boiled their grapes in great vats lined with lead for added sweetness, the diets of Nero and Caligula were rich in lead. In Tacoma, decade after decade, it rises out of the smokestack, dust drifting and settling where it may—north, south, east, and west. The unwitting populace breathes it, eats it, drinks it, and becomes it.

__________________________________

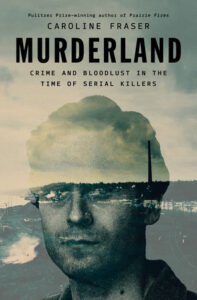

From Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers by Caroline Fraser. Copyright © 2025. Available from Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Featured image: Thorsten Lindner, used under CC BY-SA 4.0