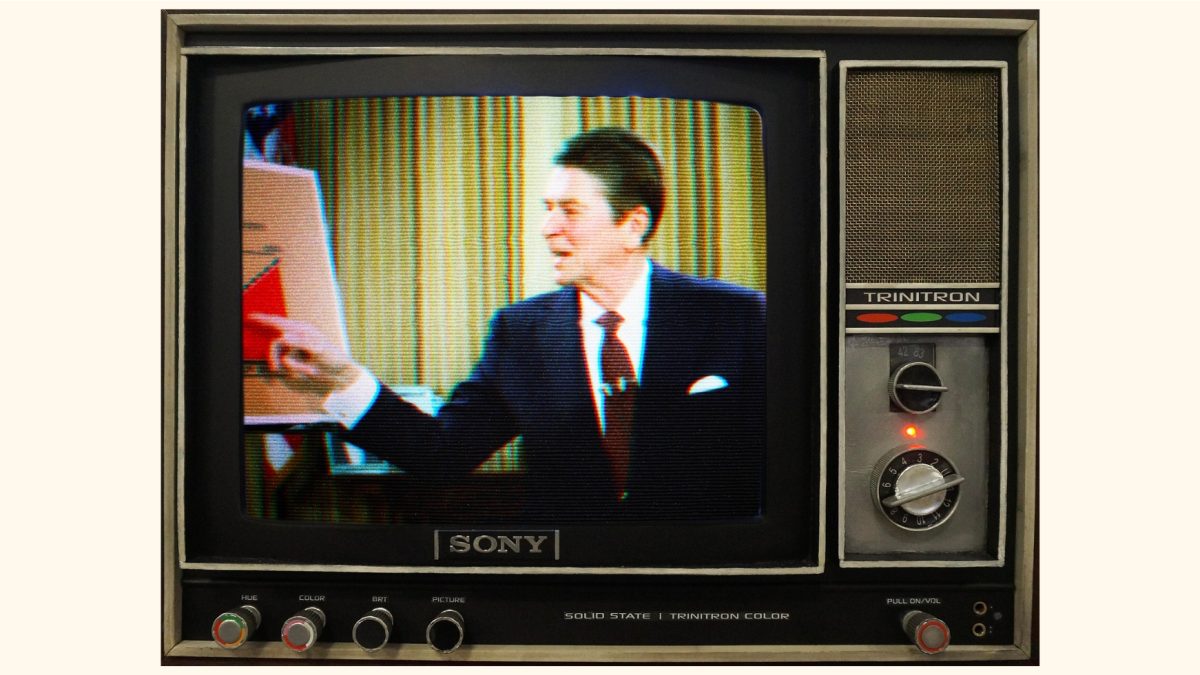

The Adolescent Family Life Act (AFLA), nicknamed the “chastity bill,” was a federal law that provided funding for teen pregnancy prevention under Ronald Reagan’s Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981. AFLA specifically funded programs that solely promoted abstinence, and specifically did not provide funding for any programs that taught about abortion or contraception. This often led to direct federal funding of religious abstinence-only programs, and led to a loss in funding for comprehensive sex ed programs.

Article continues after advertisement

In 1981, the year AFLA was signed into law, five young men in Los Angeles—all previously healthy, and all gay—died following a “rare lung infection” coupled with what appeared to be a weakened immune system. More such cases began to appear—mostly in gay men, mostly in big cities like New York and San Francisco. They presented with an aggressive cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, as well as the lung infection Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia.

In June of that year, the CDC began following this strange and tragic phenomenon. In July, the Bay Area Reporter, a weekly gay paper out of San Francisco, mentioned “Gay Men’s Pneumonia.” By the end of the year—just six months later—three hundred and thirty-seven cases had been reported. One hundred thirty men had died.

By May 1982, the mysterious illness had the name GRID: gay-related immune deficiency, so called because it seemed to affect only gay men. By September, it had a new name, and one that would stick: AIDS— acquired immune deficiency syndrome.

As researchers would come to find out, AIDS is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a sexually transmitted infection that can be contracted by anyone—not just gay men. HIV can also be spread through contact with blood, like when using shared needles, and it can be transmitted from parent to baby during pregnancy or childbirth.

It was a brutal and stunning epidemic, one that the American government ignored, stigmatized, and failed to fund research for.

The virus spread quickly and viciously. The CDC would eventually report that “the estimated number of infections increased from 20,000 in 1981 to 130,400 in 1984 and 1985.” A report from 1986 showed that AIDS patients usually died roughly fifteen months after diagnosis.

It was a brutal and stunning epidemic, one that the American government ignored, stigmatized, and failed to fund research for. Like the syphilis outbreaks at the turn of the twentieth century, when an infection was often viewed as the price one paid for the sin of extramarital sex, some now felt that AIDS was a punishment for the sin of being gay.

Perhaps no group claimed this more explicitly than American Evangelists. Jerry Falwell would express this belief most succinctly in 1987: “AIDS is a lethal judgment of God on the sin of homosexuality.”

*

Reagan’s surgeon general, C. Everett Koop—who had a penchant for wearing a full general’s uniform while in office—once called the gay rights movement “anti-family,” was a born-again Christian, and was staunchly anti-abortion. One might have assumed he would agree with Falwell. But his report on AIDS, released in October 1986, showed a different side of the nation’s doctor.

Koop wrote that “the threat of AIDS should be sufficient to permit a sex education curriculum,” and should start at the “lowest grade possible.” He mentioned third grade as a good starting point. “The need is critical,” Koop explained, “and the price of neglect is high. The lives of our young people depend on our fulfilling our responsibility.”

In addition to his call for sex ed in public schools, he also urged compassion. Recognizing a prevailing attitude that “people from certain groups ‘deserved’ their illness,” he stated in no uncertain terms: “Let us put those feelings behind us. We are fighting a disease, not people. Those who are already afflicted are sick people and need our care, as do all sick patients.”

In addition to sex ed, Koop also urged widespread condom use and testing, and—with echoes of Dr. Morrow—explained that “we can no longer afford to sidestep frank, open discussion about sexual practices.”

Koop’s report was shocking, given his political and religious affiliations. As an editorial in the Washington Post put it: “It isn’t often that Planned Parenthood and the Reagan administration see eye to eye, but a national crisis has brought them together.”

Some believed that Koop’s call might be just the thing to at last usher in a new era of sex ed in the United States. Just days after Koop’s report was released, journalist Ellen Goodman wrote that “AIDS, of all things, may be the tragic impetus to bring frank and explicit talk about human sexuality to the young.”

But angry responses came from those on the right who had regarded Koop as an ally. Phyllis Schlafly remarked, derisively, that the report sounded “as though it was written by the National Gay Task Force.” In February 1987, Koop reported that he had received a “tremendous amount of hate mail,” from conservative Christians who, like Schlafly, felt he had betrayed them.

Even some educators condemned his call for sex ed—though with less passion than Schlafly and her ilk. R. Camille Dorman, assistant superintendent of Palm Beach County, Florida, took issue with Koop’s recommendation that the instruction begin as early as third grade. “I think it would be very, very difficult to break down the material so the young children could understand it in a way that it doesn’t scare the daylights out of them,” she said.

Others worried more about the fact that AIDS education would apparently necessitate acknowledging the existence of homosexual sex. Howard Carroll of the NEA said, “To explain to children of that age what homosexuality is, this is what raises the red flag.”

There were logistical concerns as well. In some states, existing laws made it difficult to implement Koop’s suggestions. As the Salt Lake Tribune pointed out, per Utah’s state board of education, public schools could not teach about the “‘intricacies of intercourse,’ the acceptance of homosexuality’ and ;how to do it approaches to contraceptive techniques’….Utahns,” the article concluded, “obviously cannot teach their children how to avoid AIDS infections—and death—if they refuse to discuss its causes.”

But despite the mixed reactions, the federal government was willing to put its money where Koop’s mouth was. In November 1986 the Reagan administration announced that $10 million in federal funding would be allocated to “state education agencies to help them design and introduce comprehensive AIDS sex and drug education programs into the classroom.” The initiative was sponsored by the CDC. “A year from now,” Dennis Tolsma of the CDC said, “you’ll see things being taught in schools that aren’t being taught now.”

*

One epidemic did not cancel out another, and though AIDS was taking center stage nationally, teen pregnancy continued to be a pressing concern for those who were paying attention. In 1985, the Guttmacher Institute reported on a study that compared “adolescent pregnancy and childbearing in developed countries to gain some insight into the determinants of teenage reproductive behavior, especially factors that might be subject to policy changes.”

The study compared the United States with five other countries: England and Wales (categorized as one country), France, Canada, Sweden, and the Netherlands. Those countries were chosen because each had “considerably lower” rates of teen pregnancy than the U.S but similar rates of sexual activity among young people.

Compared to them, the United States had an “exceptional position,” the researchers explained. “American birthrates, abortion rates, and pregnancy rates were much higher than those of all the other countries.”

As to why this was the case, an array of societal factors emerged, but probably the most remarkable was these other countries’ “tolerance of teenage sexual activity.” These nations had approached teen-pregnancy prevention with the very methods that America had doggedly rejected for decades.

In the other nations, the study reported, “public attention was generally not directly focused on the morality of early sexual activity but, rather, was directed at a search for solutions to prevent increased teenage pregnancy and childbearing.” In the United States, meanwhile, “sex tends to be treated as a special topic, and here is much ambivalence: sex is romantic but also sinful and dirty, it is flaunted but also something to be hidden.”

Crucially, not one of these other countries had what the United States had fought so hard for: “official programs designed to discourage teenagers from having sexual relations.” The governmental obsession with abstinence was a purely American phenomenon. “The other countries,” the report noted, “tended to leave such matters to parents and churches or to teenagers’ informed judgments.”

In December 1986, the National Research Council—an arm of the National Academy of Sciences—recommended that pregnancy prevention be given “highest priority” among schools and governments, and specifically called for “more extensive sex education and the dispensing of ‘contraceptive service’ by schools and community clinics”—not the kind of programming that was funded by AFLA.

Unsurprisingly, the president of Planned Parenthood supported the council’s recommendations. Reagan’s education secretary, William Bennett, did not, instead calling school-based clinics “dumb” and predicting that they would “damage our schools and children.”

*

Stepping in at last, in March 1987, after “nearly seven years of silence,” as Julie Johnson of the Baltimore Sun put it, Reagan himself finally spoke out on AIDS. He called it “Public Health Enemy No. 1” and spoke in favor of sex ed in schools, so long as it was “taught in connection with values.” He noted that he [didn’t] “quarrel” with Koop’s public-health philosophy on sex ed, though he also opined: “When it comes to preventing AIDS, don’t medicine and morality teach the same lessons?”

This was the same conclusion that Dr. Morrow had reached eighty years prior. And it was certainly still true that abstinence from all sexual activity did necessarily preclude someone from becoming pregnant, and it also considerably reduced the risk of contracting an STI.

But now medicine offered options that hadn’t been available at the turn of the century. The modern condom in particular had emerged as an almost miraculous little device: cheap, relatively simple to use, easy enough to manufacture, and highly effective at preventing both pregnancy and STIs, including AIDS.

But for people who saw abstinence as the point, educating students on condoms was identical to promoting sex. No argument, however reasonable and fact based, could sway Schlafly and her vanguard of this notion—and now they had curricula like Sex Respect and Teen-Aid, which theoretically provided sex ed while excluding all information about contraception. With this deceitful framework now in place, states could comply with Reagan and Koop’s call for sex ed in schools without having to teach young people a single thing about how to actually prevent pregnancy or avoid STIs.

By December 1987, seventeen states and Washington, DC, had newly mandated AIDS education in their public schools—twelve more states compared to the five that had done so just seven months earlier. However, these programs differed wildly in content, showing again just how much terms like sex education could be used and abused.

Language was finessed in other ways, too. For instance, California passed a bill that declared abstinence “the primary” rather than “a primary” way of preventing AIDS. The bill’s language also claimed that other methods, like condoms, “may reduce the risk of spreading the disease.”

When it came to sex ed, the late 1980s were a time of immense debate in school districts nationwide. Yet for all the drawn-out meetings and heated deliberation, the end results were often nothing more than a vague guideline that sex ed needed to “stress abstinence,” which really meant a program that differed very little from any standard sex ed class of previous decades.

*

In January 1988, the South Carolina legislature considered a bill that required comprehensive health education in schools, including sex ed. The bill specified that “abstinence and the risk associated with sexual activity outside of marriage must be strongly emphasized” and that “abortion must not be included as a method of contraception.”

It also banned contraception distribution and abortion counseling within schools. At the time, according to Democratic state senator Nell Smith, South Carolina had an “incidence of teen-age pregnancy” that was “ninety percent higher than the national rate.” The bill was endorsed by the state board of education, the South Carolina Medical Association, and the Baptist Education and Missionary Convention, among others.

In December, a compromise was struck. Students would be taught about “both abstinence and contraceptives.”

The most controversial part of the bill included an option for local school districts to include “pregnancy prevention education” in their curricula. But the bill also included plenty of parental-rights safeguards around that portion of the class.

For a student to attend a class that addressed pregnancy prevention, a school district would have to notify parents and allow them to opt out their children. And parents were assured that any discussion of pregnancy prevention would “stress the importance of abstinence before marriage.”

Senator Smith accused critics of the bill, especially conservative religious groups, of creating a “well-organized misinformation campaign” around the proposed health-education measure. She also cited Bob Jones University—a conservative evangelical Christian school located in Greenville, South Carolina—as one of the bill’s staunchest opponents.

During a senate debate, The State newspaper reported, a small group of Republican senators “began a detailed, almost line-by-line review of the bill.” Their comments revolved around their concern that the bill’s language did not reflect “traditional, family values.” As an editorial from the Rock Hill Herald marveled in January 1988, “to hear some of these folks tell it, almost any learning about sex…is dangerous to your young people.”

In the end, the bill passed the senate with only a few additional concessions: classes would be postponed until the 1989–90 school year, and discussion of contraceptives was banned until the sixth grade. The bill’s tone remained unrelentingly conservative, insisting that teachers couldn’t “discuss abortion except to explain its complications.”

“Alternate lifestyles” (presumably meaning same-sex relationships) were not to be “discussed except in the context of sexually transmitted disease.” Teachers, the bill read, “must preach abstinence.”

In March, a legislative panel began work on reconciling the house and senate versions of the bill. One conservative on the panel was concerned that the language wasn’t strong enough to make it crystal clear to students that “homosexual behavior is illegal and immoral.”

(South Carolina’s Code of Laws, under the category “Offenses Against Morality and Decency,” included “buggery”—another word for sodomy. This type of law, which was relatively common in the United States, was usually only enforced to harm LGBTQ+ people, and in some very limited ways functioned as a “ban” on homosexuality.)

But the bill passed in April, and then South Carolina’s schools got to the work of deciding how to meet its new requirements. What followed was a waterfall of problems, as schools were forced to reckon with individual, local, and now state dictates about sex ed.

In May, school board members in Rock Hill, South Carolina, were presented with a petition. Organized by “Concerned Citizens,” the petition bore the signatures of five hundred and thirty-sex residents who had some specific suggestions for the now-mandatory sex ed program.

They wanted sex ed to be opt-in, not opt-out; they wanted no discussion of contraception until twelfth grade; and they wanted “neither homosexuality nor abortion” to be “presented as acceptable.” They also wanted the course material to “promote moral values and the benefits of postponing sexual activity until marriage,” and to “uphold the traditional institution of the family and encourage parental involvement.”

As the school board contended with the Concerned Citizens, students themselves entered the debate. One high school senior argued that “contraceptive awareness should be taught in late elementary schools.” Another student said that sex ed shouldn’t “beat around the bushes, because you’re going to find out from kids and stuff. It’s better if someone just comes and tell you about it.” And more than one of them pointed out that they had classmates who were already pregnant.

To address the situation—and prolong it—the school board appointed a committee that would, as Lisa Buie in the Rock Hill Herald explained, “oversee a state-mandated comprehensive health education program.”

And then it was all too familiar. Tedious sessions taken up with minutiae. Old grievances aired anew. Awkward compromises and concessions.

Next came harangues about a state-approved textbook called Human Sexuality, which was decried for being “too explicit” based on a “description of sexual intercourse.” Parents wanted something with more of an abstinence focus. Both Teen-Aid and Sex Respect were suggested.

In December, a compromise was struck. Students would be taught about “both abstinence and contraceptives.” Human Sexuality would be the textbook, while Teen-Aid would be used as a teacher resource.

Abstinence education was clearly finding its way into public school curricula nationwide, often at the behest of lawmakers at every level. But the American public was showing strong support for sex ed that covered more than “just say no.”

By mid-1988, one study found, the U.S. “generally supported sex education and instruction” about “AIDS, other STDs, abstinence and the prevention of pregnancy.” Clearly, the matter of sex ed remained complicated, controversial, and cloudy—with no one-size-fits-all solution in sight.

______________________________

Excerpted from The Fight for Sex Ed: The Century-Long Battle Between Truth and Doctrine by Margaret Grace Myers. Copyright 2025. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.