Dance occupies an uneasy place in the history of American art. Movement cannot be contained and presented like a painting or sculpture, and audiences are hesitant to interpret choreography like they would a visual image. When dance is the subject of a major museum exhibition, its curators face a formidable task: They must convince the public that dance matters and demonstrate how to engage dance as they would any other art form. Edges of Ailey, the Whitney Museum’s survey of the life, work, and influences of dancer and choreographer Alvin Ailey, is the latest attempt to inject dance into popular consciousness.

Ailey is, perhaps, the most recognizable figure in American dance. More than 23 million people have seen his company perform, and he has become the emblem of Black dance, not just in the United States, but around the world. Organized by Adrienne Edwards, Edges of Ailey is a cornucopia of visual art, audiovisual installations, ephemera, and Ailey’s personal archives, which Edwards retrieved from the Allan Gray Family Personal Papers of Alvin Ailey at the Black Archives of Mid-America in Kansas City, Missouri. Before he died, Ailey bequeathed a portion of his records to Gray, a friend who provided financial support starting in 1983 and placed the papers in his hometown, rather than incorporating them into the better-known Ailey collection at the Library of Congress. Permanently housed far away from typical centers of dance research, the materials available at Edges of Ailey are underutilized and provide a new look at Ailey’s history.

Regrettably, Edges of Ailey glosses over these new documents in favor of a sanitized image of a complicated man whose art and political beliefs were products of a very particular moment in time, shaped by midcentury ideas about racial liberalism, the Cold War, and rampant homophobia. Instead of homing in on Ailey, the exhibition, as its title suggests, pushes him to the periphery. Quite literally, Ailey’s archives are placed in side rooms or at the fringes beneath overwhelming displays of visual art. A lack of captions makes it impossible to identify the subjects of photographs and video recordings.

Ailey deserves the attention and celebration of a museum show. But Edges of Ailey does not satisfactorily illuminate his life and honor his accomplishments.

Alvin Ailey was born in Rogers, Texas, in 1931 to Lula Cliff, the granddaughter of a white man and Black woman who could not live together in the Jim Crow South. Ailey’s mother supported her son by picking cotton and working low-wage jobs; his father, Alvin Ailey Sr., left when his son was three months old. In 1942, Lula moved to Los Angeles, chasing lucrative work in the war effort, and Alvin followed. It was there that Ailey encountered dance, first when his high school class attended a performance by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Intrigued, Ailey continued to seek out performances, one day stumbling upon dancer-anthropologist Katherine Dunham’s Tropical Revue, which staged the Afro-Caribbean styles she researched. He also enjoyed a musical by Jack Cole, a jazz choreographer, whose movement was inflected by the Indian dance form Bharatanatyam.

Ailey did not take a dance class himself, however, until a classmate named Carmen de Lavallade coaxed him to join her at the Lester Horton Dance Theatre. Horton was a white choreographer with an integrated studio; his dances addressed themes of social injustice and were influenced by Japanese and Native American styles. The Horton company was “an intensely political milieu” where leftists and homosexuals congregated; the founders of the Mattachine Society, the first proto–gay rights organization that modeled its initial structure on the Communist Party, met at a Horton rehearsal. Ailey began studying with Horton in 1949, taking classes sporadically while also majoring in romance languages at college. In 1953, Ailey joined the company full-time; that same year, Horton died suddenly, leaving the fate of his company uncertain. Ailey stepped up and presented ideas for new choreographies, becoming the artistic director of the Lester Horton Dance Theatre.

In 1954, Ailey moved to New York with de Lavallade to perform as featured dancers in the all-Black musical House of Flowers. Based on a story by Truman Capote, the musical also had choreography by George Balanchine, the Russian émigré and founder of the New York City Ballet who picked up Black dance styles working on Broadway and in Hollywood, and Trinidadian American dancer Geoffrey Holder. The musical was “overstocked” with New York’s most talented Black dancers, including New York City Ballet’s first Black principal dancer, Arthur Mitchell (who was Ailey’s understudy). Through the House of Flowers cast, Ailey enmeshed himself in the city’s dance world, training with modern dance greats like Martha Graham and the radical New Dance Group. He decided not to return to California and instead pursued work dancing on Broadway and in the theater, studying acting with Stella Adler. After these apprentice years, Ailey finally staged his own work at the 92nd Street Y, a home for modern dance since the mid-1930s, in 1958, marking the first performance of what would become the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT).

The highlight of Edges of Ailey is a room off to the left of the main space that exquisitely chronicles the prehistory of Ailey’s company, titled “Ailey’s Influences.” Visitors learn about Horton, Dunham, and Cole, reading about their distinct techniques and watching clips of their work. One can see the precision and socially conscious subject matter of Horton’s choreography; the playful, seductive rhythms of the cumbia and shango performed by Dunham and her company; and Cole’s angular, cool jazz dance. A section devoted to Graham, from whose work Ailey consciously borrowed, reveals the source of Ailey’s theatrical sensibility, as well as his belief in the body as an expressive medium through modernist design.

Another cluster of archival materials addresses the ambivalence of Black musicals, in which Ailey performed throughout the 1950s. While these shows played into racist tropes and made spectacle of Black culture and history, they also provided careers for a legion of dancers and actors. Black performers both disavowed the genre as a caricature and believed it could be used to cultivate a “diasporic political consciousness.”

Still, even as Black performers carved out spaces for themselves onstage, Edges of Ailey demonstrates that racist traditions persisted. A clip of Jack Cole performing in blackface—stepping in for Ailey himself, in Lydia Bailey, the first American film about the Haitian revolutionary period—is especially haunting. He and other dancers execute a “voodoo ceremony,” moving in a circular formation while bent over, stomping their feet to drum patterns, articulating their hips and rolling their heads.

In the cavernous main room, on an 18-screen, wraparound installation, visitors to the Whitney can see for themselves how Ailey incorporated the influences of modern dance, theater, and Broadway musicals into his choreography. The video collage features clips from Ailey’s signature dances: Blues Suite (1958), his first evening-length piece, which staged people drinking, dancing, and flirting to blues music over the course of a night; Revelations (1960), which depicted Ailey’s “blood memories” of Black life in the rural South; and Cry (1971), an exhausting solo that traversed drudgery, anguish, and joy, dedicated to “all black women everywhere—especially our mothers.”

Revelations is Ailey’s most famous work, seen more than any other piece of American modern dance, and has become metonymy for Black dance as a genre. In the opening vignette, a band of dancers stand in a tight cluster, legs wide and arms reaching downward, hands open. Their sternums and faces arch skyward, bathing in the warm light above. Quivering voices begin the first lyrics of “I’ve Been Buked,” the Negro spiritual that Ailey first encountered as a child at his Baptist church in Southeast Texas in the 1930s, and the dancers bend at the knees, extending their right arm toward the ground while their left caresses the side of their ribs. Next, they stretch their arms into the air, palms forward, and swoop their torsos in a circle, embodying the singers’ drawn-out delivery. They fall into a layered formation and raise their arms into winglike shapes: a hopeful augury.

Though less than a minute long, the first scene of the “I’ve Been Buked” section captures something essential about Revelations and Ailey’s legacy more broadly. It is a modernist depiction of African American history that eloquently demonstrates how Black art is the spine of American culture. Those first few gestures are somber yet full of possibility, showing, as Black artists have done for centuries, that ecstasy can emerge out of the depths of pain and oppression.

Rightly, Revelations is seen as a masterpiece by audiences around the world, who purchase tickets to see the AAADT perform the work year after year. As a financial vehicle, the dance has kept the AAADT alive. Yet its dominance has also eclipsed the rest of Ailey’s oeuvre, which transcends “Black” subjects and explores the formal, sculptural qualities of the human body. Ailey wanted to use dance to convey universal emotions and ideas; “We talk too much of black art,” he said, “when we should be talking about art, just art.” Revelations, he argued, “speaks to everyone,” because “its roots are in American Negro culture, which is part of the whole country’s heritage.”

Ailey believed that Black artists were not limited to making work that reflected their race, a conviction he applied to his own choreography. The video montage also includes clips of Streams (1970), a plotless dance that explores the architecture of bodies in space; The Lark Ascending (1972), a balletic piece set to a romantic score for violin and orchestra; and A Song for You (1973), which Ailey created for star performer Dudley Williams and features elegant, lyrical movement. Williams, who was dancing for Martha Graham when Ailey recruited him, possesses the athletic technique of a Graham dancer, contracting and expanding his torso with expressive mobility. Visual art displayed beneath the video montage mirrors Ailey’s conviction that Black art was a capacious category. There are depictions of Black life in the South, like Sharecropper (1945), a somber, social realist portrait by John Biggers that depicts a farmer’s gnarled hands and exhausted expression against a shotgun house, and The Way to the Promised Land (Revival Series) (1994), a painting by Benny Andrews that captures the physicality and theatrical gestures of Baptist revival worship. Yet interspersed are colorful, upbeat works by Black abstractionists. Ellsworth Ausby’s Untitled (1970), a mauve obelisk patterned with green and blue geometric shapes, and Sam Gilliam’s Swing 64 (1964), a white canvas punctuated with an array of jewel-toned angles, are dynamic and conceptual.

Pieces commissioned for Edges of Ailey provide depth, demonstrating how contemporary artists think across media, incorporating dance into their visual practices. In Katherine Dunham: Revelation (2024), Mickalene Thomas collages rhinestones and acrylic paint over a photograph of the dancer leaping, encapsulating her dazzling allure. Two paintings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Fly Trap and A Knave Made Manifest (2024), revel in the lush grace of Ailey dancers, and Dear Mama, a sculpture of the late Judith Jamison dancing in Cry by Karon Davis, expresses her singularity as a dancer, whose technical prowess and emotive capacity defined the Ailey company throughout her tenure.

Yet the smorgasbord of paintings, collages, sculptures, and photographs that fill the central area of the exhibition is overpowering and distracts from Ailey’s choreography. The visual art is placed at eye level, whereas the video recordings of the dances are high above the crowd; visitors must crane their neck and dodge other guests to get a sustained look. If one wants to learn what they are watching, they must find a small screen wedged between the elevators and stairwell that displays the title of each work and the source of each video clip. Descriptions of the pieces and dancers’ names go unmentioned.

Beyond a brief gesture toward “civil rights and Black power movements” in a short section of wall text, Edges of Ailey does not contextualize Ailey’s distinctive approach to dance and politics. Why was universalism so attractive to Ailey as he worked to elevate Black dance as high art?

What must it have felt like to travel the world on behalf of the American government as a predominantly Black company?

A cache of archival materials in the exhibition’s rightmost room contains clues that explain Ailey’s personal philosophy, but again, go unexplained. Photographs and notes document the AAADT’s early tours throughout Southeast Asia and Australia in 1962, Africa in 1967, and the Soviet Union in 1970, all of which were funded by the State Department as part of extensive Cold War diplomacy efforts. A caption notes that the company’s first tour was supported by the Kennedy administration, but the term Cold War does not appear, and it is not clear that the other tours chronicled in the exhibition were also funded by the State Department.

During the Cold War, racism within the United States became a liability for the state’s foreign policy goals. And so, to demonstrate its pluralism, the US government sent Black artists on cultural exchange tours around the world. Ailey’s company—with its accessible repertory that depicted the triumph of Black Americans—was an ideal weapon to fight the Cold War through art.

What must it have felt like to travel the world on behalf of the American government as a predominantly Black company? How did these tours shape Ailey’s ideas about the relationship between dance and politics?

Ailey’s notes from the tours offer insight into the way he conceived of his mission. One, titled “Outline for a Lecture Demonstration in Australia,” delineates his vision of American dance: Martha Graham and Lester Horton were central, but so were jazz and “others beside Graham,” the balletic prowess of Rudolf Nureyev, as well as the influence of painters, music, and the sculptures of Henry Moore. Not once in the document do the words “Black” or “African American” appear, only “American.” Though most of Ailey’s dancers were Black, he integrated his troupe in 1962, the year the company went on its first international tour.

In an essay for Dance Magazine, published in the spring of 1968 upon returning from another State Department–sponsored tour of Africa, Ailey expressed support for cultural diplomacy efforts. “Given the turbulent developments in the ‘third world,’” he wrote, “it was very wise to send a dance company—particularly a Negro dance company—to Africa in 1967.” Still, Ailey admitted that he was also deeply affected by “the issue of colonialism,” which “colors the Africans’ outlook on almost all topics.” Following the African tour, Ailey’s liberal, integrationist views were tested. “How can you not be angry? How can you not be bitter? How can you expect to just—act like it never happened?” he screamed at his own dancers after the murder of Black Panther Fred Hampton.

Notably, it was in this period after the 1967 African tour that Ailey began to create his most political work, Masekela Langage, which premiered in 1969. A portrait of Black South Africans under apartheid, Masekela Langage resonated with contemporary American politics: “It has to be South Africa,” admitted one contemporary reviewer, “but perhaps it’s Memphis, or Bedford-Stuyvesant.” In the dance, a group gathers at a seedy hangout, equipped with wicker furniture and a jukebox. Sexual, social dancing turns to desperation: Characters fight, act out drug addiction, and lament their dead-end lives. A bloodied man bursts into the bar, recounting an episode of violence by unnamed, unseen white antagonists, dying onstage. Dancers continue, ignoring the body, and the piece ends as it started, a scene of never-ending despair. Masekela Langage put forth a more cynical vision than Ailey’s typical optimism and uplift.

Edges of Ailey also ignores Ailey’s more unsavory history in the last decade of his life, which was inflected by mania, depression, and a refusal to confront his declining health, eventually revealed to be the result of AIDS. A few pages from Ailey’s journals, scattered throughout the exhibition, expose the choreographer’s instability. Hidden between two paintings, almost illegible under the harsh gallery lighting, is a piece of paper dated 1980 that reads “Nervous breakdown 7 weeks in hosp—.” After his dear friend Joyce Trisler died of a drug overdose in the fall of 1979, Ailey began to unravel, using more drugs, behaving erratically, and seeking out impersonal, dangerous sexual encounters. “Everyone thought of cocaine as recreational in 1980,” Ailey admitted in an interview. “I became addicted.” He threw a violet fit trying to get into an ex-lover’s apartment and was arrested. The incident, which became a New York Post headline, “Alvin Ailey Runs Amok Again,” led to his stint in the mental hospital.

Over the course of the 1980s, Ailey continued to work, making new dances and building out his school and company, but grew increasingly unwell. By the late 1980s, he was having trouble swallowing and felt fatigued. In December of 1988, he finally went to the hospital, where his doctor asked if he could test for HIV. Ailey resisted but ultimately agreed. As suspected, the test was positive. When Ailey died of AIDS-related complications less than a year later, his cause of death was recorded as a terminal blood disorder, which Ailey had requested. Company members were frustrated that their mentor and artistic inspiration had not been honest, especially since AIDS was ravaging the dance community, including members of AAADT’s staff.

Younger dancers had come of age in a post-Stonewall era, when identifying as gay was both less risky and an important political position. Ailey, on the other hand, was of a generation for whom the “open secret” was an achievement and privilege. During the Lavender Scare, dancers felt lucky that their workplaces were hubs for homosexuals. The closet door was always ajar in the world of dance, where gay men congregated, even as they performed masculine, heterosexual roles onstage. Ailey could access a robust, gay social life in the dance world while he kept his personal life separate from his public-facing identity and family.

Yet Edges of Ailey mentions none of this. Instead, wall text reports that Ailey, a “gay Black man,” died of AIDS, his square on the AIDS Memorial Quilt hangs centrally, footage of a “Gay/Lesbian Pride March” flash across the main video installation, and wall text links him to “gay liberation advances.”

Perhaps if Ailey had lived longer, he would have joined the next generation of choreographers who believed that dance should be used to address the AIDS crisis or joined them in parades and protests. He was, however, a midcentury man, whose ideas and art signal a different set of political and aesthetic priorities. Those beliefs and tastes might not resonate today, but they are specific to Ailey and reflect the intensive thought and care he put into his work.

Of all the objects displayed throughout Edges of Ailey, Not Yet Titled (2024) best characterizes the choreographer as he ought to be remembered. A portrait of Ailey by Jennifer Packer commissioned for the exhibition, the painting shows Ailey in the act of thinking.

He is hunched over, his arm grips at his shoulder, and he is looking intently at something out of frame in a pose of muscled anxiety. It reveals something about Ailey’s inner turmoil, as well as his identity as an artist and intellectual, always contemplating.

Edges of Ailey would have benefitted from wrestling with Ailey’s personal life and place in history. But for some odd reason, curators chose to turn away from the greatest source of this information: Ailey’s archive, from his personal notebooks to choreography. Even as the exhibition gathers such intimate documents, it does not make them legible to its visitors. With proper context, the materials on display tell an important story and demonstrate that dance provides access to the history of the Black freedom struggle, Cold War liberalism, and the transformation of sexual politics over the course of the 20th century. Instead, Ailey and his dances disappear into the margins. Edges of Ailey, meant to recognize the choreographer, ironically helps us forget him. ![]()

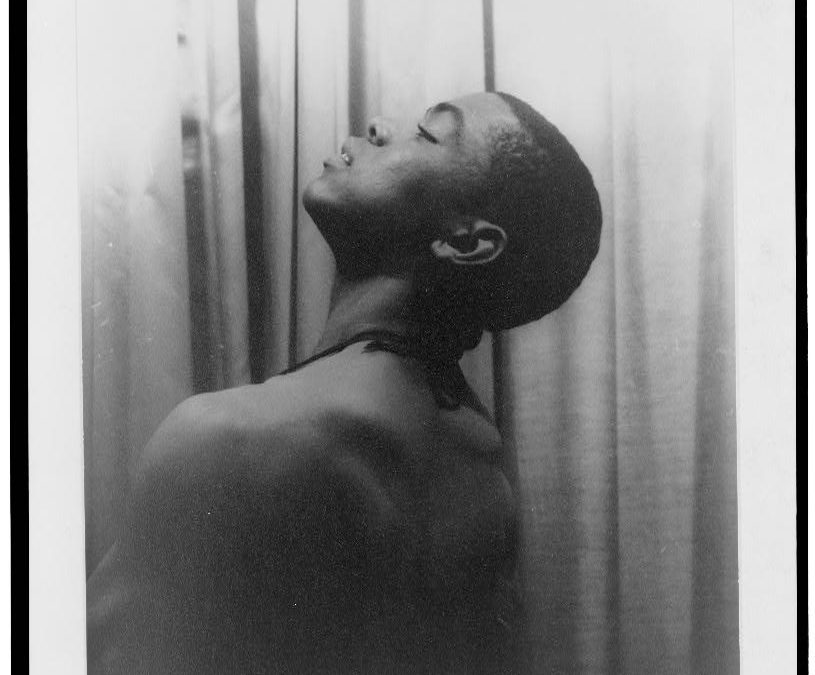

Featured image: Portrait of Alvin Ailey (1955) by Carl Van Vechten / Library of Congress.