This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Article continues after advertisement

When my final copies of my memoir Better arrived, I opened the box with my five-year-old son, Theo, and turned to the final page of acknowledgements to show him, Look, there’s your name. In that acknowledgement, I make a joke about one of our conversations that I included in the book. The conversation is a rare moment of comic relief in a book that was constantly at risk of drowning in despair: Theo is obsessed with death, and here he shares a theory about the afterlife that he calls Butt World. I write that I hope he doesn’t mind I’ve shared Butt World with the real world, and it’s an easy disclaimer because it’s an easy laugh. Underneath it is the trickier, more fearful admission: I hope you don’t mind that I’ve shared you.

I don’t know a single memoirist who hasn’t held tight, at one point or another, to one (or both) of two ideas, usually recalled with varying levels of accuracy: Anne Lamott’s reassurance that you own all of your story and “if people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better,” and, as popularized by Nora Ephron, the insistence that “everything is copy.” When Ephron died in 2012, that copy was still mostly siloed in those traditional media with high barriers of entry: film, books, print journalism.

Social media was still, fundamentally, social, far from the various platforms’ expansions into publishing. Mommy bloggers were amassing readers by chronicling (and soon monetizing) the intimate details of their children’s lives, but not yet with the hyper-speed and reach powered by our awesome and awful algorithms. Could Ephron have predicted the granularity of details shared? We might update the saying she learned from her screenwriter mother: Everything, today, is content. Is it all still fair game?

It would be years before the effects on those bloggers’ children would come to light, but now that the first generation of children have grown old enough to tell their side of the story, we’re facing a social and political reckoning with the ethics of exposing children to an audience, of exploiting them for profits they rarely share. For my part, this reckoning has involved re-evaluating my participation both as a consumer—Babies are cute! Kids are funny! Their videos make me smile!—and as a chronic poster. Far be it from me to take on the “influencer” mantle but “content creator,” with its consumerist implications, is harder to disown. I share my life on social media; I share my life in my newsletter; now, I’ve shared my life in my book. Theo is a massive part of my life, and because of this, for the first time in my decades of public oversharing, I have a reason to censor.

I’ve developed sort of squiggly parameters for social media—when Theo was a baby, I shared photos of him only on a private account; now that he’s older I mostly don’t show his face anywhere—but books, too, are content, and it was impossible for me to write mine without re-evaluating Theo’s presence and role within it. It was easier when he was a baby, when so much of my describing him was really describing my reaction to him, my understanding of him—the faraway look in his eyes that I read as contemplative, the rapid kicking of his legs that I liked to imagine as his eagerness to get out into the world.

But as he got older, the same type of observations felt almost like objectification, treating him like a curiosity to be analyzed. I tried to limit his appearances to dialogue, usually captured through my obsessive documenting of our lives. His words, our conversations, become presentations of data. It’s still intimate, but a type I’ve made peace with sharing, hoping he won’t see it as betrayal.

Writing about Theo was—is—painful because it’s a distillation of my general anxiety, and at times shame, in turning my life into content. When Theo and I are in bed and he starts asking his big questions, my phone is always close at hand so I can grab it, discreetly press record, and ask him to repeat what he just said, and the conversation—the moment—is tinged with my own ego and ambition; it’s the transmutation and sanitization of existence into art, narrative, meaning. And when I revisit those recordings to post his insights—so fascinating, enlightening, as any child’s insights are while they’re trying to make sense of the world—in an Instagram story or print them on the page, I can’t help considering his reaction if he understood the reach of those words. Of course, he will, one day.

After I showed Theo the acknowledgement, he asked me about the conversation I put in the book. He didn’t remember Butt World, so I read him the section, and he was giddy having his words presented to him. He’s had me read it to him twice since. Maybe he’ll resent it in ten or twenty years; that’s part of his story. But the conversation—which is one in a series of quick scenes about all of the ways Theo brings his preoccupation with death to me—isn’t about Theo so much as it’s about us. It’s there because it passed the one-question test that determined his every inclusion: Does this moment reveal more about me than it does about him? Better is a book about being a mother with depression, but it’s also, by dint of its very existence, about being a mother who is a writer. Both are complicated, but neither—contrary to what many, including myself, have believed—is necessarily a curse.

______________________________________________

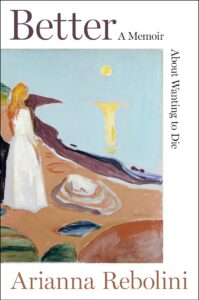

Better by Arianna Rebolini is available via Harper.