I occupy a corner of the internet where I’m largely secluded from a cis audience’s reaction to I Saw the TV Glow, the second feature from director Jane Schoenbrun. Instead, I see trans people dunk on fellow viewers who — with varying degrees of innocence — are unable to put their finger on the film’s central narrative. They wax on about fandom or a generalized call to action, pushing viewers to live their lives to the fullest, in whatever way that may mean for any given person. The cultural clash between how trans and cis viewers are receiving the film mimics the film’s central friendship and the characters’ respective relationships to the glow of their thick 90s television sets: comprehension hinges on the ability to see transition as a possibility. I Saw the TV Glow is about both transness and obsession. It explores where one starts and the other ends, how one can lead to the other, and how one can stamp out the other like a work boot over a small, rising flame.

I Saw the TV Glow follows the life of Owen, a biracial boy who grows up and grows old in the American suburbs, charting his relationship with his favorite television show, The Pink Opaque, and the coinciding friendship he develops with an older girl, Maddie, who first showed it to him. The show is the metaphorical egg inside the movie’s nest: two girls, who together make up “the Pink Opaque,” use their shared psychic connection to fight monsters of the week and the big, bad, Mr. Melancholy, who seeks to subdue them and the world they occupy in “the Midnight Realm.”

From the moment he first sees a commercial for The Pink Opaque, there is a gravitational attraction between Owen and the show and, by extension, between Owen and Maddie, as they seek comfort from the safest source available in the sprawling suburb of sameness where they spend their youth. On a Saturday night in the fall of seventh grade, after being dropped off for a fabricated sleepover, Owen walks through backyards, pink sleeping bag under arm, until he arrives at Maddie’s door to watch the show. He knows nothing of it beyond his inherent need to watch. Whether or not he enjoys it upon viewing is beside the point: he has already decided to love it because he needs it. The Pink Opaque — which Owen’s parents won’t allow him to watch because it’s a “girl show” that airs after his strict bedtime — represents one small stretch beyond the jurisdiction of the forces keeping him in a world too small for him.

The first time I saw I Saw the TV Glow in theaters, seated between my friend and boyfriend — both of whom I met on Grindr over the course of three genders — I instantly recognized Owen’s commitment to consumption based simply on the idea of what could be: an instinct he’s yet to understand, but one he’s compelled to follow. Soft and quiet tears rolled down my cheeks, my breath steady and my mind rapt, watching what felt like an archive of my own experiences projected onto a huge screen on the Upper West Side. I floated out of the theater in an afterglow reminiscent of LSD or a really good yoga class: pleased, grateful, and a little like a zealot. Much like Owen after his first viewing of The Pink Opaque, I didn’t have complete comprehension of the experience I just had, but I knew there was something tangled inside that would serve me moving forward.

I can, with relative ease, chronicle my life in obsessive units from five years old to taking my first estrogen pill. I would set my eyes on something — a movie trailer, a song, a drug, a person — and decide to love it. Even if it turned out to be shit, I would ride it until the wheels fell off. I Saw the TV Glow is the kind of movie I would have been obsessed with pre-transition. I would’ve fallen asleep to it every night in college, and, should I still be awake when it ended, I would have restarted it. Rinse and repeat until it lulled me to sleep, stealing away the thoughts of the day and the anxieties of the night, replacing them with sights and sounds, dialogue and details. I couldn’t be as empty as I felt, filled with these things.

From the moment they meet, Maddie paces ahead of Owen in every sense, from her budding sense of self to her knowledge and perspective on the show to her ability to take decisive action. Dispassionately, she leaves breadcrumbs, illuminating a path forward for him. Though they don’t watch the show together anymore, each week Maddie leaves Owen recorded VHS tapes of The Pink Opaque with a note in the school’s dark room. They don’t reunite in person again until two years and many tapes later, when they return to her basement one Saturday night to finally watch another episode together. He stares blankly into the TV as she stares intensely, brimming with emotion. Where the show breaks Maddie open, it numbs Owen.

Objects of pre-transition obsession can function as emblems of hope, a glow at the end of an endless tunnel of bedtimes, curfews, and unchosen rules to live by. But obsession functions on a system of diminishing returns. Hyperfixations lose appeal through repeated exposure, slowly becoming a stand-in for the pleasures of the past. The Pink Opaque becomes less and less powerful for Owen over time, as his once porous mind solidifies over decades of shame and internalized value judgments. The thing that once afforded him a sense of being alive no longer works, like an inhaler with a limited number of puffs.

Objects of pre-transition obsession can function as emblems of hope, a glow at the end of an endless tunnel

It’s common knowledge among transsexual artists whose work I have followed that coping mechanisms are built to fail. Last month, in an unpublished excerpt from my interview with horror writer Gretchen Felker-Martin, we spoke about living through the media we consume, in reference to I Saw the TV Glow. She asserted, “Painfully, that is not enough. You cannot sustain yourself on a diet of the hidden fantasy in childhood. It’s a lot harder to have a life than a fantasy.” Similarly, Torrey Peters (who is thanked in the credits of I Saw the TV Glow) wrote in 2021’s Detransition, Baby, “The awful part [of early transition] was watching what therapy called ‘your coping mechanisms’ flame out.”

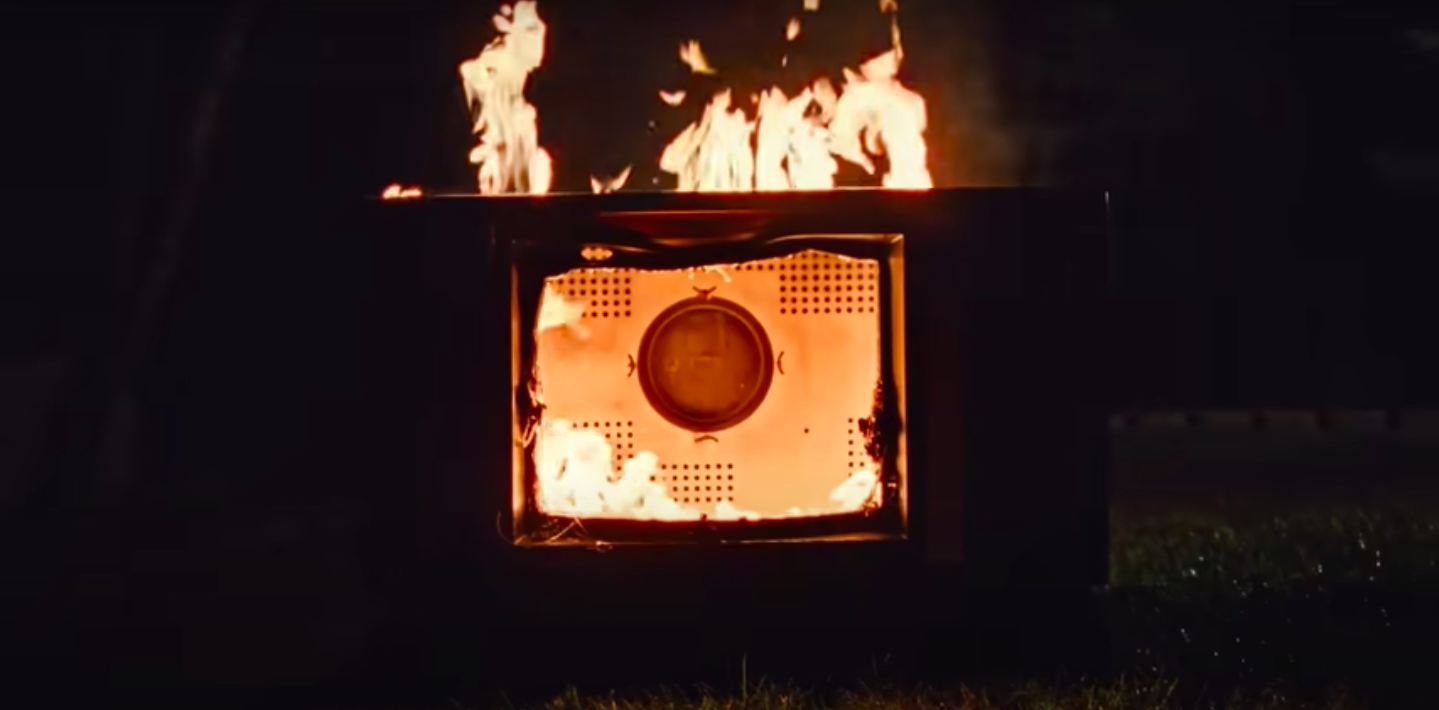

For Owen and Maddie, they literally flame out, leaving behind two sets of burning televisions: Maddie leaves hers out on her lawn after she runs away, while Owen thrusts his head through the glass of his after the show’s finale. They are, respectively, a symbol of her breaking free, and a monument to obsession worn well beyond its expiration, his rejection of possibility and a commitment to surviving on a nostalgia drip he doesn’t understand.

Shoenbrun captures the dark truth that whether you transition or not, the methods you use to keep yourself distracted or satiated will eventually fail you, leaving you as alone, scared, and discontent as before you discovered them. The film is a nightmare of grand proportions and boring days, shifting between quiet, reserved moments of loneliness and crescendos of emotional acuity that are hard to watch for reasons that feel innate rather than obvious.

From the time I was old enough to consume media and, later (but not that much later) consume alcohol and then drugs, a constant replay of consumptive habits kept a cloud of static separating myself from the world around me — and unbeknownst to me, from the world within me. During my first year of graduate school, reflecting on two decades of obsession through a cloud of dank smoke, I began to understand the circus of afflicted women whose stories had filled me as something beyond simple (albeit, exquisite) taste. During a recent sleepover, a friend characterized this type of woman I’d always been drawn to as one who holds herself under the surface of her own bath water. The summer after my first year of graduate school, as I stood in my parents’ pool reading with the sun on my back and a blunt in my hand, a different friend sent me a text proposing that the extended joy of finishing a book could never stand up to the immediate joy of hitting my blunt. And for the first time, I decided to attempt a tolerance break, not because I felt like I should, but because I wanted to.

The Midnight Realm is a place each of us can occupy under particular circumstances. Like a warm bath, it wraps inhabitants in comfort and familiarity, encouraging them to wallow in its basic pleasures, keeping our truer, more grandiose desires dormant. In its waters, our eyes stay glued to what’s immediately before us, obscuring the horizon of time in the distance, where there is light beyond the glow on a television screen or the cherry of a joint. Our comforting obsessions can hold us over until we have the opportunity for something greater. But if they become that something greater in and of themselves, they have the ability to hold us under the water until the bubbles stop.

Whether you transition or not, the methods you use to keep yourself distracted will eventually fail you

After smoking weed all day for the better part of my twenties, I watched Spirited Away for the first time during my tolerance break, on a couch in my hometown with a friend I’d met on Grindr two years before. My obsessions had consisted of movies, TV shows, drugs, and at one point, this boy. Since I stopped smoking, it felt like all of those walls had fallen. In their absence, a watershed of tears fell every day. Not necessarily tears of sadness, but tears of overwhelming feeling where there was once nothing.

As my friend fell asleep next to me, Chihiro took off into the sky, flying on Haku’s back. In the sky, a memory resurfaces in her mind of a river she fell into that carried her back to shore. “I think that was you, and your real name is Kohaku River!” she says. Haku’s dragon scales break off and spread into the air like confetti. He takes his human form once he remembers his name for the first time since becoming lost in the spirit world. The tears came, and I ran the idea repeatedly in my head for days to come in the month before starting estrogen. How lost one must be to forget something as central to the self as their own name. Realizing you’re trans feels a lot like that. Like a lost memory, found. Something so obvious finally coming into focus. Something gone that is now, all of a sudden, there. And once you look at it, it becomes undeniable.

Once Maddie has come to terms with her own transness, her relationship to The Pink Opaque is ruptured. The chasm of transition is difficult to cross, and looking back, nothing — even your favorite TV show — is the same. In the decade after high school, Maddie returns to save Owen from the complacency of the TV’s glow, but Owen maintains, “This isn’t the Midnight Realm, it’s just the suburbs.” In all of his rewatches, he can’t see The Pink Opaque for what it is: a metaphor for the un-life he leads and the beginning of the knowledge required to get beyond it.

In writing this essay, part of me expected to become obsessed with I Saw the TV Glow. I thought I would watch it every day for a week, and then this essay would pour out of me, filled with details and observations only a seasoned, transsexual obsessive could offer. That was far from true. What actually happened was that on my third watch, I cried for what felt like hours. That rush of tears articulated what I had felt when I first saw I Saw the TV Glow in theaters: it’s about living in a place I’m terrified of returning to. I talk about it constantly in therapy: slipping back into a life where sitting alone at home in the glow of the TV feels warmer than being in the company of my friends and family. Where if you cut me open, static seeps out instead of blood. Where I am not me, I am these things of other peoples’ creation.

Realizing you’re trans feels a lot like a lost memory, found.

“You’re gonna love the Midnight Realm. It’s such a wonderful, wonderful prison,” says Mr. Melancholy, as the screen shows a snow globe containing seventh-grade Owen that first time he looked into the pink glow of the television: a seed being planted into hostile ground, where it will remain forever the same, pleased to have its desires played back on a loop.

For another twenty years after Maddie returns to save him, Owen remains underground, having forgotten he is dying. The Pink Opaque appears corny to him now, a puff of his inhaler no longer brings the relief it once did, leaving him wheezing through life working at an arcade. When he finally breaks, screaming in the center of a child’s birthday party, everyone around him pauses in an unreaction. His pain, his life — the two of which can no longer be separated — exist on a parallel plane to those around him. A solution cannot be found in the material world, only the internal one.

On the floor of the bathroom, Owen cuts his chest open with a box cutter. He stands up in the mirror and pulls his ribs apart to let the glowing static out. Relief washes over his face. It can be heard in his breath. It is everything. What’s next matters less than the fact he looked in the first place. What he saw and what he chooses to do with it is a different (horror) story to tell, one that happens far beyond the glow of a television set. What matters is that there is still time.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.