This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Article continues after advertisement

Interrogating the ways different myths occupy their own unique spaces establishes pathways into existences of literary immortality, offering prisms into the art of storytelling. Myths conjure cultural juggernauts such as Game Of Thrones, Medusa, African equivalents like Mami Wata. Novelist Gayl Jones is an example of where author as myth and the work they produce take on a kind of rare, legendary, fabled status.

Jones is the great American writer you have never heard of. Her appearances and disappearances in publishing are shrouded in mystery. With Jones, author and art as myth bleed into each other. Her recent astounding work, Palmares, is set in seventeenth century colonial Brazil. It follows a young slave girl named Almeyda who moves from plantation to plantation hearing about the rumors of and searching for a liberating settlement called Palmares for fugitive slaves to live free. As Almeyda makes her journey towards this elusive mecca, both the idea of Palmares and Almeyda’s journey toward it feel like hallucinatory visions: Vibrantly conjured, indeed mythic in intention and impact. Palmares is a work that feels part fiction, part incantation, like a series of long buried ancestral memories brought to life. The writing is vivid yet taut.

On the other side of the spectrum, Natalie Haynes superb novel Stone Blind reimagines Medusa’s story with equal verve and imagination. Here, the story of Medusa as we know her, vilified and reduced, is upended. With this fresh take, Haynes cleverly gives Medusa much more dimension. It is the elasticity of this approach, the confidence to give oneself permission to reconfigure an established tale that is impressive as well as inspiring. In Haynes’ comic retelling of this ancient myth, the intertwined stories of Medusa, Perseus and Andromeda take centre stage. Audiences know Medusa, a Gorgon as a nightmare although she is a feminist icon of sorts for to look at her is to be reduced to stone from one withering stare.

Noted for the live snakes in replacement of her hair, women across time have celebrated her, a tragic figure seduced and raped by Poseidon in Athena’s temple which caused the furious goddess to punish her for her suffering at the hands of another by making her into a monster. The Olympian gods are not spared Haynes’ acerbic wit—they are selfish, ridiculous and spiteful. Haynes playfully expands myth making by stretching its confines. By creating a fuller picture which centers Medusa in her own story, Hynes creates a more dexterous Medusa, one imbued with more agency and less tragedy.

In my own writing, the process of myth making fascinates me. It is an opportunity to create historical African aesthetics in ways that feel new. I may have unwittingly attempted this whist working on my debut, Butterfly Fish, mining my imagination to recreate the eighteenth-century kingdom of Benin. I pored over brass artefacts in museums, fell down rabbit holes of research to source those hidden tales, I travelled back to Nigeria to visit the old, more rural parts of Benin that could have been lifted right off an ancient kingdom, sensing that something in the land, some alchemic process was occurring to help me write. And indeed, that trip made the world I was attempting to build come alive, beating like its own beautifully awkward vessel finding its footing in the sun stroked villages. The middle strand of the novel is the eighteenth-century retelling, bookended on either side a section set in modern London and another in 1950’s Nigeria. The thinking behind this was to give the book a kaleidoscopic feel.

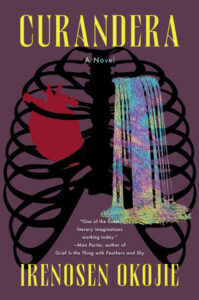

In my new novel, Curandera, I explore the aesthetics of myth again. A book on shamanism, female desire and transformation across multiple dimensions in two different time periods. Here the risk was in creating a mythical fictional mountain town, Gethsemane, in seventeenth century Cabo Verde. In conjuring this town with no blueprint that already existed, I had to travel to Cape Verde several time to research it, study the various rural landscapes, the culture as well as the spiritual practices and African spiritual practices more broadly in order to produce something that occupied its own space. I am still not sure there is one specific correct way to create a myth, what we have are variations, multiplicities with their own kinetic energies to break the world open. Reinterpretations within the remits of myth making makes writing fiction feel innovative and all the more exciting for it.

______________________________________________