This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Article continues after advertisement

I am descended from a long line of packrats, people who couldn’t get rid of anything for love or money—especially if something might prove useful or meaningful to someone, somewhere, someday. Witness the stack of albums passed down after the early death of my grandmother, followed a decade later by my father. Inside, I found his report cards, scads of carefully clipped newspaper columns detailing his every achievement, no matter how small, and every school photograph, each annotated in my grandmother’s distinctively square penmanship. And then there’s the stuff. So much stuff. Plates and placemats, yellowed bed linens and napkins, glassware, curios, and sewing kits. Inside one, I found a collection of Izod alligators, each one painstakingly removed from the white tennis shirts favored by my dad and his younger brothers since my grandmother didn’t approve of branding. And yet, despite her disapproval, none of the little alligators made it to the trash bin. Why, I asked the quiet storage unit after I stopped laughing. Did she really think she might sew them back on someday?

Given this familial urge to collect, it is likely that no one was surprised when I became an art historian, the officially sanctioned study of stuff. Of course, the sort of collection that attracts scholarly attention tends toward the rare and precious rather than Izod alligators. Questions about the provenance of paintings and sculptures of the 19th century—my area of focus—tended to list both monarchies and families of great wealth, while speculations about meaning often implicated entire cultural and social systems. The remnants of my family’s hoarding habits—including a 50s era carpet-shampooer and a pile of monogrammed ashtrays—are not comparable. At least, I didn’t think so.

When I left the profession chosen in my 20s to become a writer, my lifelong dream, I took my training with me. And, as it turned out, the sorts of questions I’d learned to ask proved incredibly useful. How old is the object, and where did it come from? Who made it? Who bought it and why? What was happening in the world when this item entered the marketplace? These sorts of considerations are the ones that bring a thing to life, often revealing its buried history.

My graduate school advisor, the brilliant Mary Sheriff, always insisted that scholarship had to follow the object, not the other way around. In other words, an idea should never shape interpretation. If it does, the resulting paper will never work, the argument like fitting a square peg into a round hole. This was drilled into me so deeply over the course of nearly a decade that it remains an integral part of my practice.

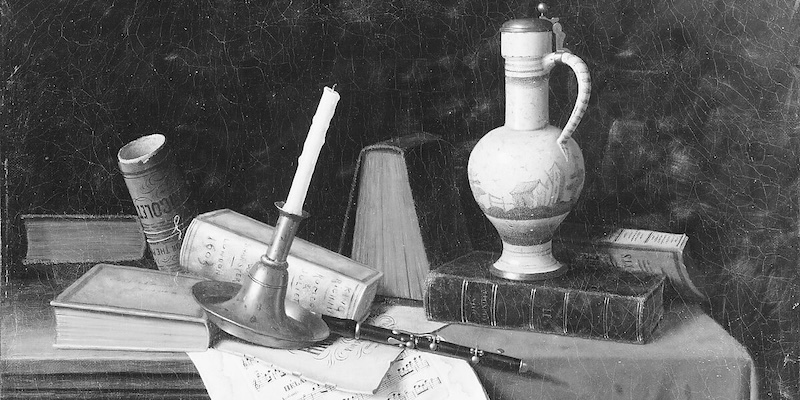

I follow the object, asking it to speak to me. Take the monogrammed ashtrays and their matching glass cups. I start with: what is the relationship between the two, and how were they used? The answer lies in the provenance. My father’s family hails from the American South, where tobacco was a way of life. People smoked all the time, even at the table, especially if spirits were poured. Which, I must assume, they were. The small glass ashtrays and the cups would have been arranged above the place setting, a fresh cigarette always within easy reach and beside it, the means to avoid shedding ashes into one’s dinner.

A scene forms: men in thin ties, leaning back in their chairs, one leg crossed over the other, haze encircling their heads. A conversation takes shape: tobacco prices, Vietnam, college unrest, and babies who won’t sleep. Someone forgets to use the handy ashtray and taps the plate instead. The hostess does not approve. She sniffs. Did this sink his application to a club? Or tank a promotion? Perhaps his child is rejected from a school for which he needs the host’s recommendation. Soon, there’s the kernel of a story.

So, much to my husband’s dismay, I struggle to dispose of the ashtrays along with many other useless things that clutter my garage. Even the most mundane tell stories. Some are quite personal, evoking vivid images of my grandparents, my father and uncles, and my brother, all gone too young, too soon. Sometimes, I ask questions that are harder to answer than when and where. I hold a glass swan in my hands, fingers exploring the grooves, a small chip at the tail. Who else touched it as I do? How was it damaged? Did it fall? Was it thrown in anger?

And how about the leather-bound book with worn edges? There’s an illegible signature on the title page. Someone must have read it. I picture a quiet corner, the book set aside, a stray to-do list wedged between the pages and forgotten. When the reader finished, did they tend to the garden? Take bread from the oven? Were they crying as they swept the crumbs from the counter?

But there is no one left to tell me, and so I can only imagine.

__________________________________________