Li-Young Lee’s first collection in a decade, The Invention of the Darling, remixes many themes from his five previous poetry books: family, exile, intimacy, and the divine. Yet somehow these plain verses feel fresh. In “Counting the Ten Thousand Things,” Lee writes,

“Start over in secret, at night

with my mother and father and the escape to…

Canaan? Bethlehem? America?

Where was it we thought was safe?”

Four quick lines recall the pain of a refugee’s journey, one that never quite arrives at the land he was promised. Since Lee’s last collection, various horsemen have come calling: a deadly pandemic, a spike in anti-Asian violence, a U.S.-enabled genocide. In Lee’s poetry, love (“the true lover lives / only to love the beloved”) is a powerful expression of resistance against external forces of harm and displacement.

Lee, born in 1957, immigrated as a child to the U.S. while fleeing violence in Indonesia directed at its ethnic Chinese population. Before embracing what would become a decorated poetry career—including a Lannan Literary Award, an American Book Award, and fellowships from the Academy of American Poets and the Guggenheim Foundation—Lee packed books in a warehouse and, with his brother, launched a fried chicken restaurant and a jewelry business. (The jewelry, made of found materials like Coke cans, was featured in Vogue and the rom-com Pretty in Pink.) In addition to his poetry, Lee has also published a memoir and a book of interviews, which often range into the philosophical and mystical.

I spoke to Lee over Zoom between the release of The Invention of the Darling and the publication of his co-translation with cosmologist Yun Wang of Laozi’s Daoist verse Dao De Jing.

April Yee: You said in 2016 to the LA Review of Books,

“The Chinese say, ‘In order to write poems, it’s a process of Yin, the practice of Yin beckoning to Yang.’ Yin is yielding. That is, you practice yielding. We live in a culture in which yielding is not a virtue. Retiring is not a virtue. Staying silent is not a virtue.”

I’m curious about these ideas of silence versus aggression, Yin and Yang, and the practice of poetry, this idea of aesthetics and activism. Particularly in the current environment—which feels like a silly thing to say because something terrible is always happening in the world. But I think the particular way in which things are happening today engenders a type of complicity, particularly as Americans, that’s possibly different than before. And so I’m curious about that relationship to Yin and yielding and silence and retiring, whether that’s changed—and also about your relationship to activism today.

Li-Young Lee: I feel as if this Yin becomes more important in my life, more and more and more important. It’s almost exclusively what I’m interested in at the moment and, you know, it’s not weakness. In the martial arts, when you throw a strike, the more Yin you have in that strike, the more precise and the more powerful it is. Even Western boxers know this when they say, “Sit inside your punches.” Think about that. The punch is going out, but they’re saying, “Sit inside the punch,” right?

Poetry is the logic of all logic. And it’s a logic beyond reason.

The longer I live, the more I realize that the world is a koan to me. It’s an instance of something beyond reasoning, beyond rationality, beyond understanding, beyond my grasp. I live in complete mystery all the time. I don’t know how to deal with it. Now, it seems to me that out of desperation and fear, I’ve been telling myself I can fix it, I can control the world. But in my trying to fix things, I’ve ruined so many things. I cannot tell you. I believed that I was trying to fix the world. I ruined so many things, personal things I live with every day. The world is no better. I didn’t fix the world. And so I realized I better practice this koan attitude. And that finally poetry is the logic of all logic. And it’s a logic beyond reason. It’s the logic of God. It’s the logic of my mother. She endured so much.

From the day our neighbor in Indonesia raised the machete to my parents and said, “I have to drink your blood, I just have to”—the world became beyond my understanding. Nothing will be able to explain that. I played with that man’s children. And the flip of a switch, he was standing there covered in sweat, spattered in blood. I don’t know who else he had killed. And he says to my family, “I have to drink your blood. You don’t understand, I have to.”

How am I going to fix that? He’s not the only one. And if I’d talked to him, he might have had reason to. Is there a reason to kill your neighbor? I don’t know. The horror is just beyond us. The beauty is beyond description. The mystery is beyond description. The terror is beyond description. The joy is beyond description. It’s all beyond me. I don’t know what I’m going to do. I keep thinking that poetic logic will be able to account for it or something.

AY: That memory you just raised, you know, reminds me of some of my own family histories. And I suppose what’s different is that those things have happened. We’re left to grapple with them and the different ways that they manifest in our consciousness and in our bodies. But is there some kind of obligation in the more Yang sense to prevent that [violence] from happening, and how do we do that as poets?

LL: The first thing for me, when I discovered that murderer in me, I thought on a daily basis… I’m not murdering people, but I found that I’m capable of the same kind of violence, the same kind of rage, the same kind of anger, the same kind of reactive whatever-it-was that man was experiencing. I realized—it’s so hard to accept—I’m no different than him.

So I started to think, during the activism part—I want to tell you maybe I was usually unlucky. I was very involved with activism, but a lot of the people I was involved with were the worst people in the world.

AY: Can I ask what specific areas you were working on?

LL: When we first came to Chicago, this area was crime-infested, and there was just garbage everywhere, dirt lots, a lot of drugs being sold openly on the street. So we began a neighborhood watch. We began a local neighborhood gardening project. We built gardens. We stood watch. We did outreach to the projects, young people. We got a lot of them to finish high school. I mean, we started from the ground. We weren’t just beautifying the things. We started teaching meditation, martial arts reading, after-school programmes. Years of this. Years. We had some success stories, a lot of success stories. People finishing college, people going to college for the first time.

But at the same time it wasn’t even a drop in the bucket. It was nothing. Everything just kept getting worse. And on top of it the people working there were so ego-bound and so glory-bound and fame-bound and everybody saw the activism as a way to—I didn’t understand it—as a way to gain more influence or as a way to gain political power in the neighborhood.

After I saw that, I thought, I’m not against activism. But if there’s not inner work going on, I just don’t see any hope. I don’t think there’s a political solution. I don’t think there’s a social solution to a spiritual crisis.

AY: I have a question more in the vein of what we call craft or process. I was really curious about the way that you wrote your memoir and about that desire to write the book in a single night. And correct me if I’m wrong, but even when it would be revised, it would also be rewritten in the span of a night, or as close to a night—a couple of nights—as you could get to as possible. This kind of thing nearing automatic writing, or maybe it’s nocturnal prayer, or whatever it is. I’m curious if that’s also the mode in which you write poetry and if that’s something—that long form—that you might ever want to return to, and what specific knowledge that mode of creation can unlock?

The practice of poetry is the practice of polarities—which is Tai Chi.

LL: I’m troubled by the long form. I keep noticing my ego is really at play in the long form. There’s something about it thinks it’s huge. The ego thinks, “Look, look, look, I’m just so big. I’m so competitive. There’s so much of me.”

I feel as if I’m beginning to wonder about what’s driving that, because I thought I was trying to make a model of the universe. My models aren’t other works of art. My models are things in nature. So when I set out to write that [memoir], I thought, that has to be the universe. So it has to have everything in it. It’s impossible.

And I feel as if what might be more interesting right now is a model of the universe in a small lyric poem. The tension between the size, the smallness of the lyric poem and the largeness of the universe—that polarity might be the thing that I need. Because I feel like the practice of poetry is the practice of polarities—which is Tai Chi, right?

AY: One of the polarities that I noticed in your work in general but maybe more specifically in The Invention of the Darling is the polarity between the specific and the nonspecific. You have this poem, “Call a Body”:

“The one with bones

is born of the boneless.The one with a face

is born of the faceless.Too obvious?

The one with skin

is born of the borderless.

The one was features

is born of that without features.Not concrete enough?“

I’m really curious about who that’s addressed to. For me, I read that almost as a challenge to the kind of poet’s critic [saying], “This image is not tethered to detail sufficiently for the detail-hungry reader.”

And then a couple of poems later, there’s this much more specific one. That’s “Thus the World is Made,” where the speaker of the poem is saying,

“We fled the soldiers.

We fled the police.

We fled the revolutionaries.

We fled the mobs.”

And so there’s this feeding into that specificity and that biography, or supposed biography, that the reader is often hungry for. So I’m curious about how you balance that in your writing, this drive between these two polarities and the reader’s hunger, that third party.

LL: The most I can do is demonstrate my openness and ready assimilation of the divine. It’s the same thing a shaman does. That’s what they do for the community. They enact possession by the divine. But the third party, I’m not looking at the third party. That poem “Call a Body” is a dialogue between the lover and the beloved. All of my poems are a dialogue between lover and beloved. Sometimes that dialogue is full of love. Sometimes that dialogue is inflected with stress, and maybe even strife. Both the lover and the beloved, I think, is the founding paradigm of all my work.

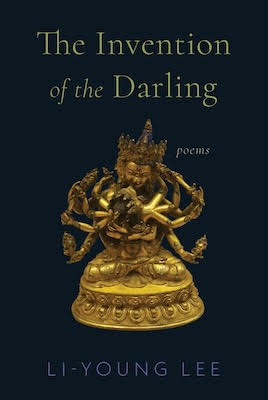

The cover of The Invention of the Darling is the image of Yin-Yang. That is the tantric Buddhist image of the union, the male and the female in conjugation, staring into each other’s eyes. They said out of that encounter with the male and the female—the polarities of weak force, strong force, Yin and Yang—out of that encounter, the whole world manifests.

And I want to clarify here, that when I talk about silence, I’m not talking about the white page. I think nobody understands that the white page isn’t silence. It is full of noise. So a lot of times I see people using this convention where they leave a lot of white space. It just fills up with noise. Poetry has this very powerful effect. It creates silence. That’s why it’s so hard to face the white page. It’s not the silence. It’s the noise.

I have to say Emily Dickinson does this so superbly. I don’t even know how she was able to—she builds her own silence within which to hear the poem.

AY: I wonder if that’s a flaw of the form of the book, in general, and that Emily Dickinson wasn’t writing into the book form.

I want to write with a daemon hand and a Christ-like heart.

LL: Yeah, I think that’s catastrophic to write into a book form. I’ve never written into a book form. I feel as if the poem is the thing. The book is just a collection of those instances. I think poetry is the practice of ultimate polarity, ultimate stillness, and ultimate motion. It’s this tension between absolute stillness or silence and the speed of the fastest thought. And then there’s the polarity between male and female. There’s the polarity between denotation and connotation. There’s the polarity between the One and the All, between the specific and the general.

The One and the All is one of the highest-tension polarities in lyric poem. It’s the One, the mortal being, inflecting the All that is eternity. And somehow, that polarity, if it’s not experienced in the poem—if the poem is just an instance for the ego and it isn’t this polarity between mortality and eternity—somehow there’s not enough tension in the poem, you know?

AY: Back in 1995, in an interview with Bomb, you said, “When I’m writing, I’m trying to stand neck and neck with Whitman or Melville, or for that matter, the utterances of Christ in the New Testament, or the Epistles of Paul.” I’m curious, three decades on, if those are still those who you’re trying to stand with today.

LL: I want God to speak through me. I’m tired of my own voice. I’m tired of me. I’m tired of all my own schemes, all my egos and machinations. I’m tired of being lost. I’m tired of following my ego. I’m tired of the whole thing. I just want God to live my life. I want God to speak those poems. And I feel as if—you know, Melville went mad. I mean, his best books are insane. There’s some sort of daemon, you know. I want to write with a daemon hand and a Christ-like heart. Does that make sense?

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.