In honor of Literary Hub’s tenth birthday, we asked over 200 authors, editors, booksellers, publishing professionals, and other literary luminaries to weigh in on a few questions about the past, present, and future of the literary world. We will be sharing their opinions on various subjects with you over the next weeks, but to start, we’ve collated some of the best answers on one of our favorite questions: what’s the best book you’ve read recently?

NB that “recently,” in this case, meant the last 25 years (we’re long-term thinkers), and that rather than ask respondents to choose the best book published in the last 25 years, we asked them simply to pick the best books they read in the last 25 years, to get a more accurate sense of, well, what people are reading, be it new or old. Here are some of their responses, which reflect very little consensus—suggesting that books might not be dying in a monotonous, homogeneous heap after all:

*

James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. It’s a perfect novel, and reads like it could have been published this year.

–Kelsey McKinney, author and co-owner at Defector

Giovanni’s Room. “I stand at the window of this great house in the south of France as night falls, the night which is leading me to the most terrible morning of my life. I have a drink in my hand, there is a bottle at my elbow. I watch my reflection in the darkening gleam of the window pane. My reflection is tall, perhaps rather like an arrow, my blond hair gleams. My face is like a face you have seen many times. My ancestors conquered a continent, pushing across death-laden plains, until they came to an ocean which faced away from Europe into a darker past.”

That’s the first paragraph. It’s beautiful and embodied, and it immediately positions the reader just-so, so intelligently and succinctly, into a depressive act of atonement, and the text is so immersed in desire and the work is so descriptive, it feels beautiful. I love melancholy, grief, love, and this book fuses all I love.

–Terese Marie Mailhot, author

Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss. It’s tight, highly original, and really speaks to the dangers that arise, particularly for girls and women, when a society glorifies its past and clings to a myopic understanding of history for its identity.

–Quan Barry, writer

The Door by Magda Szabó, translated from the Hungarian by Len Rix. It was not written in the last 25 years, but I read it recently. It’s one of those books that shreds every narrative rule and yet (or rather because of that) works so beautifully. It’s riveting character sketch for 4/5 and then all the plot is in the last 1/5 and you don’t mind at all. Also it has one of the best dog characters in literature.

–Rebecca Makkai, writer

The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields—it’s big, it’s ambitious, it’s hilarious. There’s a sentence on every page that you’ll want to underline (unless you’re tone deaf or without pencil). And no one reads it any more. But they should. Winning a Pulitzer doesn’t always please posterity. But this one—a novel about how our pasts our continually revised, to comic and tragic effect—deserves to be remembered and rediscovered.

–Jonathan Lee, novelist & TV writer

The Last Samurai, by Helen DeWitt. I don’t know a single other book that is as brilliant and as captivating as this novel. This is proof that a novel doesn’t need to be watered down in its style or ideas in order to hold a reader’s attention. I wish we all aspired to write books this ambitious and good.

–Isle McElroy, novelist

Lol. Um, Proust?

–Nick During, publicist

Impossible question, but I’ll pick the last book I loved, which is by Benjamin Labatut. When We Cease to Understand the World is gorgeous, prosaic, and saying something very important about violence, genius, madness.

–Ingrid Rojas Contreras, writer

This is obviously an incredibly difficult question so I’m going to cheat and submit four: The Bear, by Andrew Krivak (the best apocalyptic parenting narrative there is); Margaret the First, by Danielle Dutton (compulsively readable, wickedly erudite); When We Cease to Understand the World, by Benjamin Labatut (mindblowing and perfect); and Underland, by Robert Macfarlane (somehow capturing the full breadth of what it means to be human in a book about underground spaces). Ok. If I had to pick just one, I’d go with the Labatut.

–Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub EIC

Philip Roth, Sabbath’s Theater—for the best last line and most romantic golden shower scene of all time.

–Jess Bergman, editor

The Swan Book by Alexis Wright. A satire, not only did it gaff contemporary aboriginal life but also presented the problem of species diversity and the climate disaster in Australia.

–Terese Svoboda, writer

Oblivion: Stories by David Foster Wallace. A deeply disturbing masterpiece, the last great work of an author facing his own ultimate decline.

–Porochista Khakpour, author

25 years ago I was 20 years old, and I had read nothing except Frank O’Hara and Jane Eyre. That’s about when I read Kelly Link for the first time, and so you know what, I’m going to go ahead and say The Book of Love, Kelly’s first novel, which came out last year, because I’d been waiting twenty years for it and it was worth every second of the wait.

–Emma Straub, novelist and bookseller

I was pretty blown away by Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake. The novel intertwines elements of espionage with philosophical explorations of human history, environmentalism, and the complexities of identity and manipulation. There was an aspect to the story that really hit my heart hard in Bruno Lacombe’s radical philosophy, which posits that modern humans have lost their essential connection to the primal elements of existence. He believes that civilization has stripped people of their “salt”—their raw, untamed nature—leaving them spiritually and physically deficient. This idea weaves through the novel as Sadie, the protagonist, becomes increasingly drawn to Bruno’s worldview, challenging her sense of self and mission. The theme explores how people navigate authenticity, survival, and the cost of returning to a more “natural” state in a world shaped by technology and control.

–Brittany Ackerman, writer

City of Saints and Madmen by Jeff VanderMeer. I can draw a straight line from reading this book as a freshman in college to me sitting here, writing to you right now. It’s likely not an exaggeration to say that I would not be who I am without this book—I certainly wouldn’t be a writer. The book is a stitch-up of several stories, but it isn’t a story collection and it isn’t even really a novel in stories—it’s something more complicated, which is part of its charm: it is a novel wherein the main ‘character’ is the city of Ambergris and the stories recounted within are telling the city’s story, even when they’re sometimes very character-driven and, on their own, otherwise rather ‘traditional’ in their way. Reading this book not only infected my dreams (to this day, I dream of strolling down Albemuth Boulevard) but it changed the way I understood story. It’s certainly the most important book of my adult life, which for me is the ultimate metric of ‘best’.

–Drew Broussard, writer/bookseller/Lit Hub Podcasts Editor

I guarantee no one is going to have this same answer but honestly, I was taken apart and put back together by The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Frye by Rachel Joyce. AND also Half a Life by Darin Strauss.

–Mira Ptacin, narrative journalist and memoirist

The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante—it’s as close to flawless as a novel can get.

–Erin Somers, novelist and books reporter

Because there’s no way I can possibly pick a favorite, here is a tie. The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton is a perfect novel. And One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabo was the most involving, sweeping reading experience I’ve ever had.

–Brittany K. Allen, writer

All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews or Cassandra at the Wedding by Dorothy Baker. Any book that centers love, friendship, dependence, entwinement, with humor, grace, sadness, pathos, that has such immense warmth and care at the core, is the best kind of book to me.

–Julia Hass, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet.

–Matthew Salesses, writer

Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. Lush, satirical, terrifying, endlessly clever, and sometimes when I reread it I sympathize with these terrible children and sometimes I think I’m peering directly into hell. This one is ripped off so often by writers who don’t come close to conjuring its magic—I think the imitators forget how funny this book is, how deeply pleasurable the prose.

–Brittany Cavallaro, novelist and poet

This is too difficult to answer especially since the last 25 years takes me to 13 years old, so basically this period is my entire reading history. So I’ll just pick the first best book I remember reading which was A Wrinkle In Time by Madeline L’Engle.

–Hannah Lillith Assadi, novelist

2666 by Roberto Bolaño and Natasha Wimmer (because it was devastating and delightful); close runner-up would be Vernon Subutex 1 by Virginie Despentes and Frank Wynne (because it’s a spellbinding, breathtaking feat).

–Jennifer Croft, writer and translator

Vernon Subutex (trilogy) by Virginie Despentes, translated by Frank Wynne. Very few people write about the unhoused in contemporary literature, and why not? Maybe it’s because to write fiction takes immense privilege; Despentes does so with style and significance. It tackles a gentrifying Paris, fascism, racism, Islamophobia, fame, money, sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. Her hero, Vernon, is a fallen Gen-Xer trying to survive it all—and the book is critical of his generation’s hypocrisies. It has a kaleidoscope of characters I still think about. A huge series in France, less so in the U.S., and that boggles my mind because it’s a masterpiece.

–Alex Gilvarry, author

My God, how dare you make me choose. Okay: Edgar Telles Ribiero, His Own Man, translated by Kim Hastings.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Managing Editor

White Oleander by Janet Fitch. This is the first book I ever encountered that seemed to understand the very particular sensation of being a girl surviving in the world, living in grief for a mother who is still alive but unreachable. It is unmatched in its lyric beauty and reads like an epic. It goes to such surprising territory and captures California’s rough beauty. It’s a hypnotizing book and no matter how many times I read it, I burst into tears every time.

–Chelsea Bieker, novelist

Anna Karenina. The way it investigates human psychology absolutely floored me the first time I read it, and I make it a habit to reread the book every year, which teaches me something new every time.

–Esmé Weijun Wang, writer

Five books immediately come to mind that fundamentally changed my sense of how words can speak to human experience—all of which I read in the last 25 years and none of which were published in the last 25 years (sorry): Moby-Dick, James Baldwin’s essays, Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Annie Ernaux’s Simple Passion, and Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook—cliché, maybe, but they were all ecstatic reading experiences I’ll never forget.

On the contemporary side, it’s poetry that mostly comes to mind: Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds is a book that still stays with me—his novels are poetry, too, don’t let anyone fool you. Ecco’s 2015 anthology of Jorie Graham’s poetry and that doorstopper of Louise Glück’s poetry FSG put out in 2012 also mean a lot to me. But also John Jeremiah Sullivan’s book of essays Pulphead seems criminally under-read, and I would add Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time to this list, too. Ok, also Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station and 10:04, which I think are best read as a diptych.

–Elianna Kan, literary agent

The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje. I read this novel in 2008, as a junior in college. The book came to me at that impressionable time of my life when I secretly wanted to be a writer but didn’t have the courage to admit it aloud. The language, the characters, the final image—they imprinted in me in a way that has changed the way I write and see art.

–Crystal Hana Kim, writer

Love Me Back by Merritt Tierce, because it changed my perspective about what fictional motherhood can look and sound like.

–Courtney Maum, author and publishing expert

Heavy, for its unwavering honesty and brutality.

–Nathan Deuel, writer and teacher

I’m torn between Linda Gregerson’s Magnetic North and Frank Bidart’s Half-Life: Collected Poems 1965-2016. Bidart’s tracks the development and remarkable range of a truly singular voice in American poetry—elegies, persona poems, the intimate and the abstract, the anxieties and perversions and intimacies of historical and invented figures in addition to “the poet” himself. Gregerson’s shows her at the peak of her signature tercets, weaving together the microscopic and the grand threads of science, art, and history into wonderfully rich sonic landscapes. Gregerson’s is a book, a mind, a poetics that demand an attentive, intelligent reader—something I wish more books of poetry would do.

–Corey Van Landingham, poet

C’mon, this is impossible! I’m inclined to say the Wolf Hall trilogy since they saw me through the early pandemic and, like much else from that time, they live large in my memory.

–Stephen Sparks, bookseller

Dodge Rose by Jack Cox (Dalkey Archive, 2016). This miraculous debut novel has all the hallmarks of a modernist masterpiece, yet it never feels like an imitation or a throwback. In its lithe 201 pages, Cox manages to weave a complex narrative about a pair of young women and the recently deceased widow whose estate they are trying to get in order while incorporating everything from dense Australian property law legalese to onomatopoeic piano-busting pyrotechnics, from eerie Sebaldian black-and-white photos to bravura Joycean punctuation-free streams of consciousness. It’s a book about ownership, history, family, law, revenge, and—in a somewhat subterranean way—colonialism. By burying this story of the indigenous peoples of Australia beneath the larger narrative, letting it only emerge through hints and hushes, Cox mirrors, and thus deliberately showcases, the ways in which colonial powers subjugate through fictions (whether literary, historical, legal, economic, etc). In a better world, novels of this level of sophistication, beauty, erudition, ambiguity, and play would come along more frequently and dominate the literary discourse.

–Tyler Malone, writer and professor

John Berger, Portraits. This book has universes within universes. It is humane, political, searching, wise, as if speaking to us from all times. It holds a lifetime of trying to see.

–Madeleine Thien, novelist

Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. A beautiful and curious book.

–James Folta, Lit Hub Staff Writer

Yu Miri’s The End of August (tr. Morgan Giles) is a colossally ambitious and impossibly inventive novel that reckons with cycles of colonial violence and familial betrayal. There are so many incredible ideas on display in this book (one chapter follows a single gust of wind from one side of town to the other, weaving in and out of scenes through drafty windows and chimneys) and you’d be hard pressed to find a book more densely-packed with those moments that you make you go “wow I didn’t even know you could do that!”

–James Webster, Marketing Director (Deep Vellum / Dalkey Archive)

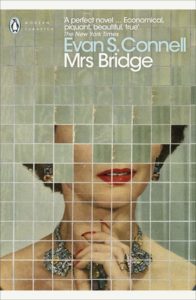

Not published within the last 25 years, but Mrs. Bridge was an absolute revelation as I was trying to figure out if I could write fiction. It cracked open the possibilities of novels in ways I’m still thinking about.

–Jessie Gaynor, writer & Lit Hub editor

I’m going to go with one of my favorites. A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan. It was a book that I got to read for review as a blank template—my galley, which I still have, doesn’t include a single blurb. Even the hardcover only got advance praise from Kirkus and PW. Now we know that it was brilliantly written, heartbreaking, encompassed art and fandom, how we live in the present moment, and is refreshingly innovative in form. A blazing prizewinner. But to be able to encounter that from the start and think, Wow! Everyone should read this! And then they did. What a cool book experience.

–Carolyn Kellogg, writer and editor

László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below, tr. Ottilie Mulzet, has been the most enduringly impactful to me personally.

–Brad Johnson, bookseller

At the Autopsy of Vaslav Njinski by Bridget Lowe. It’s the Exile In Guyville of the 21st century thus far, has influenced many poets’ new work, and is an authentic extension of the work of both Dickinson and Plath.

–Peter Mishler, poet and Lit Hub contributing editor

I’m only thirty, so this basically a question that applies to my entire reading life! If I had to pick one, I’d have to say, reading Franny and Zooey at 19 changed the entire course of my life in at least 4 or 5 different ways.

–Sarah McEachern, Rights Director at Deep Vellum