“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal….”

–Thomas Jefferson,

The Declaration of Independence (1776)“I have never seen, to my knowledge, a man, woman, or child, that was in favor of producing a perfect equality, socially and politically, between the negro and white people.”

–Abraham Lincoln,

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates (1858)*

The founding era is the Big Bang in the American political universe. In one compressed moment during the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the American colonies won their independence from Great Britain, announced to the world the enlightened values on which their bold experiment in republican government rested, created the first nation-sized republic in modern history, and established the political institutions designed to preserve and protect republican principles for the foreseeable future. These achievements made the United States the political model of the liberal state, which displaced the monarchical dynasties of Europe in the nineteenth century, then rescued Western civilization from the totalitarian despotisms of Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union in the twentieth.

Most of these achievements were unprecedented, and perhaps the largest achievement of all was to shift the tectonic plates of Western political thought by insisting that power did not flow downward from God to monarchs and then feudal aristocracies, but instead flowed upward from that quasi-mystical entity called “the people” to their elected representatives. Small wonder that the British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead observed that there were only two occasions in Western history when the political elite of an emerging empire behaved as well as anyone could reasonably expect: the first occasion was Rome under Caesar Augustus; the second was the United States under the founding generation.

These mindlessly celebratory and naïvely judgmental responses to the founders are in fact complementary cartoons, the front and back sides of the same childlike portrait that we periodically rotate.

All of the above can justifiably claim to be the historical truth, but it is not the whole truth. For there are two legacies of the founding era that must be noticed, and both qualify as enormous tragedies. Alongside their impressive achievements, the founding generation failed to reach a just accommodation with the Native American population, and failed to end slavery or, more realistically, put it on the road to extinction. Both failures led directly to horrific consequences: a policy of genocide in slow motion for Native Americans; and the bloodiest war in American history to end slavery.

Taken together, these triumphal and tragic elements constitute the ingredients for an epic historical narrative that defies all moralistic categories, a story rooted in the coexistence of grandeur and failure, brilliance and blindness, grace and sin. No aspiring historian could wish for more. It cries out for a protégé of Henry Adams to expose the ironies of it all: the overlapping ways that achievements on one side of the political equation closed off options on the other side; how leaders trapped in contradictions invented denial mechanisms to avoid facing their hypocrisy; how some of the wisest men of our greatest generation became mentally paralyzed once race entered the conversation. In this narrative format, all saints are also sinners (Thomas Jefferson is a singular figure who leads the list in both categories), the high moral ground turns out to be a utopia—Greek for “nowhere”—and all the gods are laughing.

But that is not the way the story has been told. Instead, we have been asked to choose between two competing narratives of the founding. One features the founders as demigods who were permitted to glimpse the eternal truths, or, as Ralph Waldo Emerson once put it, “to see God face to face.” The other is crowded with a cast of despicable villains who collectively comprise the deadest, whitest males in American history. These mindlessly celebratory and naïvely judgmental responses to the founders are in fact complementary cartoons, the front and back sides of the same childlike portrait that we periodically rotate, like adolescents fluctuating between the emotional imperatives of unconditional love and Oedipal hate.

*

My own efforts during the past four decades have been dedicated to rescuing the founders from the electromagnetic field we have constructed around them. It seemed self-evident to me from the start that the mythology surrounding the revolutionary generation was a fog bank that needed to be blown away. Charles Francis Adams, the grandson of John Adams, made the point most succinctly long ago: “We are beginning to forget that the patriots of former days were men like ourselves. And we are almost irresistibly led to ascribe to them in our imaginations certain gigantic proportions and superhuman qualities without reflecting that this at once robs their character of consistency and their virtues of all merit.”

What seemed self-evident to me seemed misguided and almost sacrilegious to a surprising number of self-described history buffs, who regarded the words “God shed his grace on thee” as sacred script. It dawned on me gradually that, for the same reason that religions require divinely inspired prophets, emerging nations seem to require mythological heroes. Think Ulysses for Greece, Romulus and Remus for Rome, King Arthur for England. Such legendary figures, all fictional characters, link the messy uncertainties of nation building to a transcendent region of certainty and truth that defies criticism and doubt. It is what William James called “the will to believe.”

For that reason, it made patriotic sense to capitalize the Founding Fathers, construct temples to them on the Mall and Tidal Basin, carve their faces into Mount Rushmore. During the formative phase of the infant American republic, when its survival was still problematic, iconic founders performed a valuable function as reliable sources of unquestioned wisdom, a veritable gallery of Delphic oracles available on demand.

The mythologized version of the founding encountered early opposition from prominent members of the revolutionary generation, who registered their disbelief that the all-consuming crisis they remembered so well was being transformed into a childish fairy tale. John Adams led the way, brandishing his customary irreverence: “It is a common observation in Europe that nothing is so false as modern history,” Adams observed. “And I should add that nothing is so false as modern history except modern American history.” In the Adams formulation, the true history was about chance, contingency, and unintended consequences, about political leaders who were all improvising on the edge of catastrophe. Perhaps he had missed it, he joked, but no member of the Continental Congress represented a colony called Mount Olympus. In an effort to display his own modesty—not a natural act for Adams—he made a point of objecting to his own sanctification: “Don’t call me ‘Godlike Adams,’ ‘The Father of His Country,’ or ‘The Founder of the American Empire.’ These titles belong to no man, but the American people in general.”

*

Ah, “the American people in general.” There it is, the great rallying point in American history, the secular equivalent of heaven, the place to go when all else fails in the search for an impregnable political fortress that no patriotic American would dare to attack.

As far as the American founding is concerned, it is a lie—or, if you prefer less disturbing language, a massive delusion. None of the prominent founders believed they were creating a democracy. In fact, the term itself was an epithet throughout the founding era, a way to describe ignorant and easily deceived popular majorities, perpetually vulnerable to demagogues. The last quarter of the eighteenth century was a pre-democratic era, and all efforts to read a Jacksonian or Tocquevillian faith in the wisdom of the common man into the American founding are misleading distortions.

The political lodestar for the revolutionary generation was not “the people” but, rather, “the public,” as in “res publica,” or public things. In that world, the public interest seldom coincided with popular opinion. The public interest was the long-term interest of the people, which a majority of people at any given time seldom comprehended, mostly because they were born, lived their lives, and died within a three-hour horse ride. They could not think nationally or, as Hamilton preferred, continentally, because their mental horizons were quite literally limited by their day-to-day experience of life. During the war for independence, they strongly supported local militia units, but refused to extend that support to the Continental Army.

The point merits mention as we prepare to engage the tragic side of the American founding, since the dominant assumption within the American political universe is that democracy is always an asset for the side committed to worthy causes. The exact opposite was true when it came to avoiding Indian removal or ending slavery. Any political movement to achieve those goals needed to come from the top down rather than the bottom up. Why? Because a sizable portion of the white population sought to pursue their happiness by acquiring land occupied by Native Americans. And an even larger proportion of the same segment of American society, even those willing to contemplate the abolition of slavery, could not imagine a post-emancipation America of racial equality as anything but a nightmare.

*

If the original sin of American history is slavery, and racism its toxic residue, the original sin for American historians is “presentism,” the presumption that our political and moral values now are wholly reliable standards of truth and justice for the assessment of our predecessors then. Think of the Christian missionary who wonders why her prospective African converts have never heard of Jesus.

The British historian Herbert Butterfield coined the term “the presentistic fallacy.” “The study of the past with one eye, so to speak on the present,” he wrote, “is the source of all sins and sophistries in history, starting with the simplest of them, the anachronism. It is the fallacy into which we fall when we are giving the judgments that seem the most assuredly self-evident.” For our purposes, a historical rather than presentistic approach must regard the founding era as a foreign country, and all inhabitants of that place in time can only be assessed, much less judged, after we have internalized their values and prevailing assumptions. Any trip back in time that begins as a quest for heroes or villains is fatally flawed from the start. Much like structural racism, presentism is an embedded presumption of moral supremacy to be avoided at all costs.

Avoiding this fallacy is not an easy thing to do. The founders have become valuable trophies in the ongoing culture wars, ardently claimed by both sides. The pro-American side emphasizes the triumphs, airbrushes out the tragedies, and veers close to patriotic mythology. The anti-American side focuses exclusively on the tragedies, usually makes slavery the chief argument for the prosecution, and dismisses the triumphs as hypocritical rhetoric. Both sides think more like lawyers than historians, deriving their satisfaction from scoring points as advocates for their respective clients. Nothing is lost in this interpretive framework except historical truth in its most disarming configurations.

*

And so, as we prepare to travel back in time to that foreign country called the founding, there are three false trails that need to be marked at the start, three misguided assumptions virtually certain to lead us astray.

Whether they knew it or not, the window of opportunity to implement the egalitarian agenda of the American Revolution was closing.

First, the prominent founders were neither demigods nor devils, and embracing either stereotype tells us more about ourselves than it does about them. Second, our understandable affection for democracy must be put aside, in part because the founding generation did not share our faith in “the people,” and in part because the vast majority of white people then—even more so than now—embraced racial presumptions and prejudices that rendered the prospects of an emancipated black population unimaginable. Third, the moralistic agenda that some historians brandish so proudly is both fatally flawed and richly ironic, the former because might-have-been history is not really history at all, the latter because the egalitarian assumptions they celebrate all had their origins in the founding era they seek to demonize.

The late, great historian of slavery, David Brion Davis, even coined a phrase, “the perishability of revolutionary time,” designed to remind us of the almost boundless optimism generated by the war for independence. “As later antislavery writers looked back upon the Revolution,” Davis observed, “they discovered a time of selfless commitment, when the people possessed the willpower to assume that all problems, no matter how huge, were solvable. It was therefore imperative to act while individual and national feelings were still alive to the principles of justice and human equality.”

Such ideological exuberance was obviously unsustainable, which was Davis’s main point. Any effort to put slavery on the road to extinction had to happen while the revolutionary embers were still glowing, before memories of what they called “The Cause” faded into the middle distance. Whether they knew it or not, the window of opportunity to implement the egalitarian agenda of the American Revolution was closing.

Virtually all the prominent founders were thinking in the opposite direction. From their perspective, any frontal assault on slavery put at risk the political unity necessary to win the war, then to assure southern support for a nation-sized republic. Slavery was the self-evident contradiction that must be lived with until the infant American republic survived infancy. From their perspective, deferring the slavery issue rendered the triumphs of the founding possible; confronting it frontally rendered them impossible. Those enamored with the idea that justice delayed is justice denied might consider the alternative scenario provided by the French and Russian revolutions, where justice imposed led to justice destroyed, in France taking the form of the guillotine and Napoleon, in Russia the firing squad wall and Lenin, then Stalin. If the founders had done what some of my colleagues have denounced them for not doing, the American republic we currently and proudly inhabit would never have come into existence.

The only way to end slavery at the founding was to create a federal government empowered to make domestic and foreign policy for the states. The only way to assure that a Constitution possessing such powers was ratified was to keep slavery off the agenda. The only way to understand the thought process of the most prominent founders is to inhabit that dilemma.

*

If we move to a higher altitude, we will be witnessing the first chapter in a long-standing American story. Let’s call it the backlash pattern. Briefly put, every step forward toward racial equality generates a backlash from a significant portion of the white population. What Martin Luther King called “the arc of the moral universe” is really an undulating up-down syndrome. It is an inherently paradoxical pattern, since racism surges only after some semblance of racial equality becomes foreseeable.

We should recognize the pattern when it first appears during the American founding, because we are currently living through its most recent manifestation in the movement to “Make America Great Again.” And we should expect to see it again in or about 2045, when demographers predict that the white population of the United States will become a statistical minority.

__________________________________

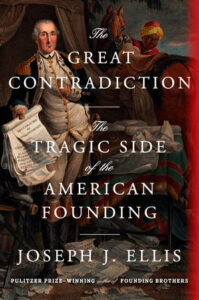

From The Great Contradiction: The Tragic Side of the American Founding by Joseph J. Ellis. Copyright © 2025 by Joseph J. Ellis. Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.